Lebanese filmmaker Jocelyne Saab died on Monday in Paris after a long illness. She was at her book launch less than three weeks earlier, and was eloquent, as peppy as possible, and there was still mischief in her eyes.

As Saab once remarked, the effects of the Lebanese civil war showed up in her body (she was in a wheelchair at the launch), but she went out fighting, and she lived to see her first book of photography published – an overview of a life's work.

Searching for authenticity

It makes perfect sense that Saab's work has appeared as an art book. Born in 1948, she began working as a television journalist just before the Lebanese civil war began in 1975, and moved on to make documentary and fiction films, and then photography.

She always reflected on the meaning of images and how they are received. Her documentary films, although depictions of reality, contain a certain amount of surrealism, social realism and poetry, and traces of these are evident in her book Zones de Guerre – or War Zones – published by Les Editions de L'Oeil and edited by film historian and critic Nicole Brenez. The images are taken from film stills and location shots, and the book opens with text in English, French and Arabic by the poet, playwright and artist Etel Adnan, and it ends with a short essay, also in three languages, by the poet and historian Elias Sanbar. Both writers were close friends of Saab's.

The idea for the book project began over three years ago, and involved a lengthy selection process.

"Between the stills, and a huge collection of photographs that have never been shown before, I was searching for an authenticity that would document what happened over the past 50 years in the Middle East region," Saab said at the launch in Paris in December. "I wanted to see how these images held up over time."

Inside her collection

In 1982, during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Saab's 150-year-old house burnt down and her archives from past work were lost. "I looked for stills in the films that expressed ideas about life, and everything that is hidden in life," Saab said.

She chose not to put captions on the photos themselves in order to leave people free to interpret them but detailed descriptions appear at the end of the book, and seeing them listed gives you an idea of the tremendous and courageous body of work that Saab accumulated during her career. Her collection is only made more impressive by the fact that she was a Middle Eastern woman who began covering wars when western female reporters were few and far between – and she was steadfast in her freedom of expression.

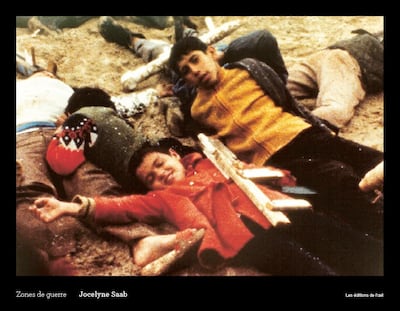

The cover of the book is a good example of the effect Saab hoped to achieve with her photographs. The grainy image shows children dressed in brightly colored sweaters lying together in a heap on the sand. For a second one is horrified – could this be the image of a massacre? Look closer and you are relieved to see that a little girl is smiling, and that she is very much alive. Still, the image is unnerving, and when you find it again amid a series of stills on pages 17-22, and then flip to the back of the book for the captions, it is immediately apparent why – the images are taken from the documentary film, Children of War, shot just after the Karantina massacre in Beirut, in January 1976. The massacre was carried out by Lebanese Forces militiamen, mainly Christian Phalangists, who entered the slum which housed Palestinian refugees and poor Lebanese, Syrian and Kurdish families, killed over 1,000 civilians and expelled thousands of others to West Beirut.

Grasping the essence of the conflict

As Saab told film historian Olivier Hadouchi in a series of interviews between 2010 and 2013, she learnt that a group of children, whose parents had been executed, had fled to the beach cottages on the once fashionable Saint Simon and Saint Michel beaches. She bought paper and coloured pencils and, accompanied by her director of photography, went to see the children and asked them if she could film them playing.

"And they play war, on the beach, but it quickly becomes very violent, so much so that I have to tell them to stop playing and I have to bring two of them to the hospital to get stitches because they've been injured," she said. "Then we come back. And that's when the most powerful moment occurs. They were a bit sheepish, as three of them were injured, but it was as if they were resurrecting the violence around them that they had sustained and accumulated within – don't forget that they had emerged from a massacre.

"I found them between the chalets arranged as a chic little village, and I suggested that we continue filming. And there, these children, wounded and traumatised by what had happened, liberated themselves from all of this by reenacting the massacre. And I filmed them. I gathered my film canisters, took the first plane to Paris, and ran to the TV studios."

The photographs in the book are arranged chronologically, with the first shots taken from her 1975 film Lebanon in Turmoil. It was described by Adnan in her foreword as "an extraordinary work that captured the Lebanese milieu in which the war began better than any other written or filmed account of the subject. With her political courage, moral integrity and profound intelligence, Jocelyne instinctively grasped the essence of the conflict."

A return to Beirut

Saab, in turn, considered Adnan's 1978 novel Sitt Marie Rose to be the best book written about the civil war.

There are also images from a 1977 reportage on the Sahara desert when Spain pulled out of its former colony between Mauritania and Morocco, the Cairo cemetery which houses a slum, or impressive frames of Tehran, which remind us of how powerful the images of the Iranian revolution were. Then, in 1982, during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Saab returned to Beirut, and the book provides a series of images that bring home what it was like to be on the ground.

We see a young woman with a microphone in front of a burnt-out house – it is Saab's and she is reporting for her documentary Beirut, My City. She chose stills from the same film showing unbearably thin and handicapped children who had been moved from a zone being shelled by the Israeli army to a safer facility. As Saab told Hadouchi, she and fellow journalists had heard of the children's plight and thought of the children constantly, taking strength from the news of their evacuation. "That gave us strength. When news of the children's evacuation came to us, it was as if we'd won a victory," Saab had said.

The emotionally-charged departure of Palestinian troops leaving Beirut in 1982 are recorded here, including the iconic image of Saab herself with a camera on a ship. Saab was authorised, allegedly by Yasser Arafat, to board the ironically named Atlantis and film the departure for her documentary entitled The Ship of Exile.

A brave and uncompromising vision

Saab also spent a significant amount of time in Egypt shooting documentaries, but also for her 2005 feature film, Dunia, Kiss me not on the Eyes, which addresses the topic of sensuality, and also touches on the subject of female genital mutilation. Saab was censored by the Egyptian government and received death threats but carried through with her film which she said took up seven years of her life. Her beautiful photographs in War Zones, taken in Egypt, of light filtering through textiles overhead are almost like revenge for Saab, who said she wanted to show that, in this filtered light which comes through all fissures, "sensuality is everywhere."

The grainy images are evocative but are also an indication of the technical difficulty of enlarging stills from primarily 16-millimeter films. For this, Saab used a film lab in Germany. Last but not least, Saab was able to produce her book thanks to the filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, who provided financing. Godard used footage from Saab's documentary Children of War in his latest film, The Image Book, which screened at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival.

Saab's photographic panorama of her life's work is testament to her brave and uncompromising vision. Her generation was born into an world of social change, ideology and violence, yet Saab never fell prey to ideology in her work, rather, she was intent on capturing images of humanity in all its disparities.

______________________

Read more:

Lebanon must be allowed to break free from its political stasis

Comment: Across the Middle East, new political paradigms are being shaped

Lebanon on brink of economic ruin, finance minister warns

______________________