Oil prices slumped on Friday as the news broke of US president Donald Trump’s positive coronavirus test. Conventional wisdom has it that his Democratic challenger, Joe Biden, would be bad for the industry. But this stale view defies both history and reality.

As the details of the president’s positive test emerged on Friday morning, Brent crude fell below $40 per barrel to its lowest level since June. US jobs data was disappointing, a stimulus package is still deadlocked, Opec output has been on the rise, and second and third waves of the virus are sweeping through the US, Europe and the Middle East. Uncertainty over the US election has shaken stock markets and oil futures.

At least since the 1970s, the American petroleum industry has generally disliked Democrats. Most major producing states – Texas, Oklahoma, Alaska, North Dakota – have been solidly Republican, though Texas has become more contestable as its economy has diversified. Harold Hamm, an Oklahoma oil-man who founded shale giant Continental, is one of Donald Trump’s close confidants.

Yet Jimmy Carter and Barack Obama, probably the two presidents most loathed by oil barons, are also the two modern leaders who have been best for the US oil business.

As the Democratic senator from Louisiana, Bennett Johnston, said in the 1970s, “I see virtually none of the independent oil producers for Carter … we’ve gotten higher drilling rig counts, more dollars being spent, more activity, more profits being made by oil people than ever before. But do they like Carter? Oh no, they hate him because of his rhetoric.”

Michael Webber, professor of energy policy at the University of Texas in Austin, expressed a similar point about Mr Obama to Forbes in 2012: “They hate him, but he hasn’t done a thing to hurt them.”

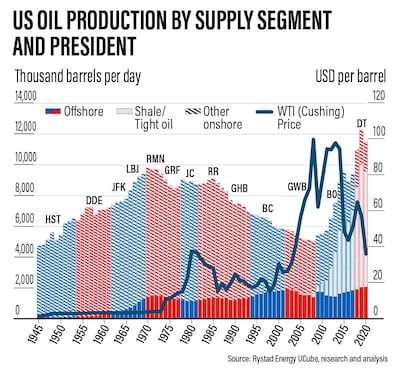

In fact, Mr Obama presided over a historic boom: oil prices were mostly high, because of economic recovery, civil war in Libya and his sanctions on Iran. He did not create the US shale revolution, but he did not stop it either. In fact, crude oil production had bottomed out at about 5 million barrels per day when Mr Obama took office; it then soared to a record 9.6 million bpd by May 2015, before slipping back after oil prices tumbled.

His administration approved several US liquefied natural gas export facilities, despite opposition from environmentalists and complaints from industry that this would raise domestic prices. Though they imposed a moratorium on drilling in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico following the disastrous May 2010 Macondo blow-out, the world’s worst ever accidental oil spill, this was only in place for six months.

The American oil business has been nervous about Mr Biden and running mate Kamala Harris. Leaving aside the specifically climate-focussed elements, his energy plan promises no new leasing on public lands. He would no doubt reverse Donald Trump’s anti-regulation agenda, including restoring measures to prevent methane leakage from petroleum operations, and cutting the wasteful flaring of unwanted gas. He would not open new areas in the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge or along the east coast for drilling – though last month, Mr Trump also halted plans to allow exploration offshore the key swing states of Florida and North Carolina. If Mr Biden’s policies do cut US output, that will drive up world oil and gas prices.

But in the medium term, Mr Biden’s impact on US oil depends on two much more consequential issues than policies on leasing or regulation. The first is what he would do on Iran. If he rejoins the joint nuclear deal and relaxes sanctions, some 1.5-1.8 million barrels per day of oil exports could return within a year to the market, and eventually up to 2.5 million bpd.

Given the complex domestic and international politics, and corporate uncertainty over sanctions implementation, it is unlikely Tehran would immediately return to world markets. But when it does, Opec+ would likely have to respond with further output cuts or risk its deal falling apart entirely. Prices would remain lower for longer, a challenge to struggling shale producers.

The second issue is even more important. There will be no sustainable recovery in any energy market until the coronavirus pandemic is contained and a solid economic revival is underway.

If Mr Biden can turn around America’s flailing healthcare response, if an effective vaccine becomes available, if stimulus and rebuilding plans pass, that will have the most positive effect on reviving energy demand in addition to prices and investment around the world. Mr Biden and his centrist constituency see jobs, trade and domestic manufacturing as important as the environment – in fact, all are increasingly inseparable.

In the long term, the question for the US petroleum business is whether it wants to become coal – a shrinking, failing industry dependent on legacy assets and handouts – or whether it can be part of a clean energy vision.

Mr Carter set the stage for both the shale and renewable energy booms, signing on tax breaks for early development of hydraulic fracturing, solar and wind power, and establishing the Department of Energy. Mr Obama’s post-financial crisis stimulus focussed heavily on clean energy, batteries, electric vehicles and energy efficiency. Under his administration, solar and wind power rose from 1 percent of US electricity to 9 per cent.

Now, some American oil firms, such as Occidental, are grappling with climate change, opening facilities to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Hydrogen, geothermal, biofuels, offshore renewable energy and electric vehicle charging are other big opportunities.

But too much of the US industry has put itself on the wrong side of the climate challenge, lobbying against modest regulations and undermining scientific findings.

With or without Washington, the EU and China, California and Wall Street, are going carbon-neutral. Instead of the reflexive hostility they levelled at Messrs Carter and Obama, oil business leaders would do better to build a constructive relationship.

Robin M. Mills is CEO of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis