Unlike the MC5, their neighbours in late 1960s Detroit, The Stooges had no transformative agenda and no revolutionary plans. They listened to some of the same music, played shows at some of the same places, but they were not, as a rhetorical question of the time had it, "part of the solution". The Stooges were happy as they were - being part of the problem. Before they played, the band psyched themselves into assault mode, their mantra ("Kill! Kill! Kill!"), a poisonously negative yin to the supposedly dreamlike yang of their musical era. Their name for this collective state, memorialised in their song Down On the Street, was "o mind".

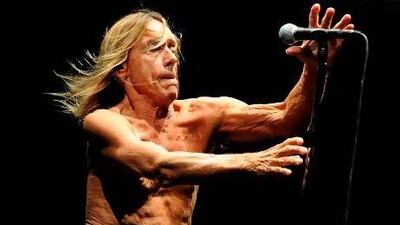

The lead singer of such a group is perhaps not the first person you would still expect to occupy a berth in Wikipedia's category "Living musicians". And yet, though he has not always prospered, Iggy Pop (real name Jim Osterberg: the "Iggy" is from his first band, the Iguanas, the "Pop" from Jim Pop, a local Detroit man who Iggy resembled when he first shaved off his own eyebrows) has at least endured. Now, with his new album, he returns to somewhere fairly near where he started.

As with his band's classic 1973 album Raw Power, Ready To Die is an album credited to Iggy and The Stooges (an important musical/semantic point), and is of 34 minutes duration. As with the earlier recording, there are two ballads included here, except that these now sound less like the tangled product of a mind in disarray, and more like bossa nova numbers by Lou Reed. Most importantly, as with Raw Power, this features the unmistakable talents of a not universally well-liked man named James Williamson.

Until his retirement a couple of years ago, Williamson had spent the last 35 years at Sony Electronics as the vice president in charge of "technology standards". In 1971, however, he was employed in something like the diametric opposite of that role: as second guitarist in the fast-disintegrating Stooges. When David Bowie miraculously secured a deal as a solo artist for the talented but narcotically degenerating Iggy, it was with Williamson that Pop collaborated on new songs. In doing so, he supplanted original guitarist Ron Asheton and began working under new signage: Iggy and The Stooges.

With Ready To Die, Iggy continues a retrospective process that he began as long ago as his 2003 solo album Skull Ring. There, after years of his so-so albums being greeted as a "real return to form", while failing to deliver much of the expected mythos, Iggy regrouped for several tracks with Ron Asheton (on inventive, yet monolithic guitar), and Scott Asheton (on drums), the powerhouse behind the original Stooges band. A new Stooges album, The Weirdness, arrived in 2007. More would likely have followed, had Ron Asheton not died in 2009. Then, in 2010, much as he did in 1972, James Williamson supplanted Ron Asheton.

Although their shows have reportedly been excellent, it would be unrealistic to suppose that men now in their 60s would be able to bottle anything like the same kind of lightning on record that they did in their 20s. So it duly proves, but everyone involved is certainly still trying. From the title, to the cover, (Iggy caught in a marksman's scope, garlanded with dynamite - a bomb primed to go off), down to the personnel (joining Pop, Williamson and Scott Asheton are vintage Stooges sidemen such as Scott Thurston [keyboards] and Steve Mackay [saxophone],) the effort has been made to make this a restoration project that retains as many original features as possible.

To write songs worthy of the savage Stooges name, however, proves to be a difficult task. The opening Burn features a characteristically roaming Williamson riff (his guitar playing is brutal, but unlike Ron Asheton's, never simple), while on Job, Iggy draws a comparison between his own situation and that of a young man in dead-end employment. Gun, the fourth track, compounds the sense of monosyllabic frustration. Here, amid much profanity, Iggy ponders whether the proper protest against militaristic America is to himself take out a gun and begin shooting.

Beyond the authentic personnel, there are certainly signifiers here of what we might understand as being "Stooge-like" music (loud guitar riffs; a certain swaggering attitude), but without these really being what we might expect or want from Iggy and The Stooges in 2013. For a band noted for its directness, on several occasions here, for example, it's hard to know what Iggy is driving at. You might not have known precisely what was intended in 1973 when he said he was a "street-fighting cheetah with a heart full of napalm", but you certainly got the general idea. When he says, as he does on Burn that "the goddess of beauty is beckoning to me", you genuinely have no idea what he's on about.

If one had to quantify the problem, it would be to say that Iggy and The Stooges were not a band designed to be "forward compatible" - as the technological definition has it, "to gracefully accept input from later versions of itself". The band was very much convened on a "use once and destroy" basis and as such, this album struggles to convincingly accommodate within its boundaries all that has happened since.

People change, and in the years since he was a chaotic, self-harming Stooge, Iggy Pop has been an addict, got sober, and remains the successful writer/performer of albums as brilliant as The Idiot and Lust For Life. He's been married, made poor decisions, kept a career going in the musical wilderness of the 1980s, acted in movies, gone through a painful divorce, and progressively revealed more and more of himself: a cultured, humorous and intelligent man of mature character. He is said to dine in his home wearing a dinner jacket, but no shirt, trousers or underpants. He is a generous musical collaborator. Uniquely among any rock star interviewee in history, he asks you what you might be interested in.

How can you satisfactorily accommodate anything like that complexity in a rock 'n' roll format that takes pride in its lack of evolution? That must be what Mick Jagger asks himself before he places another call to Wyclef Jean. Or conversely what leads Black Sabbath or Johnny Cash to the door of a producer like Rick Rubin. It's an attempt to isolate and painstakingly mine the essence. With this particular album, however, it doesn't feel as if that search has been entered into - it's as if on some level, the band don't really think they're worth it. That, at least, is an authentically negative Stooges position.

That's not to say there aren't good pieces on here. Pop/Williamson (as their Kill City demo album of 1975 abundantly proved) was a fruitful ongoing post-Stooges songwriting team, and the likes of second track Sex and Money, with decent intervention from Mackay's fruity saxophone, happily recalls that era. Ready to Die, the title track, has a sprawling riff that meets modern requirements while also honouring its historical obligations. Final track The Departed, meanwhile, quotes the riff from I Wanna Be Your Dog (the definitive Stooges composition), but as an elegy. Used like this, it becomes a valediction to the fallen Ron Asheton, and as such provides a more impressive indication of what the band might be capable of, and a more thoughtful exploration of what the title of the album might mean.

Elsewhere, however, we find DD's, a puerile song that would struggle to find a place on a better album. An example of a better album would of course be The Next Day, the current release by Iggy Pop's sometime friend and collaborator, David Bowie. As with this album, Bowie's is a record that knowingly feeds on his own past glories. As with this one, it features old friends and co-workers, and trades on his audience's expectations. Unlike this one, though, Bowie's is an album with a more mature understanding of time and legacy.

As time goes on, there are obviously fewer of a finite number of hands left for an artist to play. Bowie, the strategist, has made his magnificently-considered move. Iggy, the instinctual artist, has thrown something down, heedless of the consequences. Still confident, perhaps, that whatever happens, he will have the charisma to ride out the imperfections, and against the odds, live to fight another day.

John Robinson is associate editor of Uncut and the Guardian Guide's rock critic. He lives in London.