"How he lied. Because he did lie."

“And haven’t I been resisting the truth all along? Didn’t I bend and bash and break the facts?”

Both these quotes are from The Woman in the Window, a psychological thriller by first-time American novelist A J Finn. In the 13 months since its release, the book has topped international bestseller lists and is being adapted for an inevitably anticlimactic Hollywood movie. Finn promoted the novel around the world, speaking of the shock he felt about his six-figure advance, of his high-flying publishing career in both Britain and America, his doctoral research at Oxford and his battles with cancer.

And then last month, many of these claims were revealed to be, for want of a better word, a fiction. In an article in the New Yorker, Ian Parker revealed that Finn was a frequent and possibly pathological liar, with a history of falsifying qualifications, inventing job offers to negotiate lucrative promotions, exaggerating serious family illnesses, lying about having a brain tumour (which he said was to cover up his struggles with bipolar disorder) and waging a one-man corporate war against rivals, which included sending emails from fake accounts that he created himself.

The affair raises an avalanche of questions, mainly for publishers who apparently were so charmed by Finn they either neglected to check his credentials or simply didn't care whether or not they were true.

After all, here was a privileged, white, American man who made them money. There were clues to Finn's dualities before Parker's exposé. For one thing, "A J Finn" really is a fiction, a nom de plume for Daniel Mallory. In interviews, Finn-Mallory has spoken relentlessly about his love for Patricia Highsmith's Tom Ripley in The Talented Mr Ripley, a duplicitous psychopath who hid in plain sight, and his admiration for Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train both of which featured characters who pulled the wool over everyone's eyes.

And then there's The Woman in the Window itself, which I reviewed critically on publication. Reading this again, after hearing the truth about Mallory, I felt curiously justified, not only because I disliked the book, but also at the nature of that dislike: namely its inauthenticity.

"[One] inescapable irony of a plot driven so relentlessly by surprise is how unsurprising it feels," I wrote at the time. "The Woman at the Window is a veritable encyclopaedia of classic thriller tropes: from Patricia Highsmith through Hitchcock's Rear Window to Gone-Girl-on-a-Train … The biggest mystery is why Stephen King called the book 'totally original', unless a 'not' or 'un' has been deleted."

Read in retrospect, The Woman in the Window now teems with hints about Finn-Mallory's own allegedly deceitful nature. "Something can't be strictly true," our psychiatrist heroine Anna is told by her former business partner, Dr Wesley Brill. "It's either true or it isn't. It's either real or it's not." Here is the novel's slippery raison d'etre in concentrated form. Truth and reality are the two things poor Anna, addled by drink, isolation and melancholy, simply can't pin down.

This raises intriguing questions. What does Finn-Mallory’s apparent duality tell us about fiction? Was his proclivity for scheming and fantasy in his everyday life the perfect preparation for the plot twists of a thriller? What is fiction anyway but a series of fabricated people doing fabricated things in fabricated places? In short: do liars make the best, or at least the most successful, novelists?

The sensitive, ultra-competitive Finn-Mallory may be disconcerted to know that he's not the first pathological fibber to write a hit novel. First among equals is England's Jeffrey Archer, politician turned bestselling author, whose conviction for perjury in 2001 proved to be the tip of a vast sham iceberg. Archer, like Mallory, fabricated academic qualifications, but he also lied about expenses, and even about plagiarising a short story he had judged in a writing competition. It would seem that the machinations required to navigate a political career provide the perfect training for writing fiction.

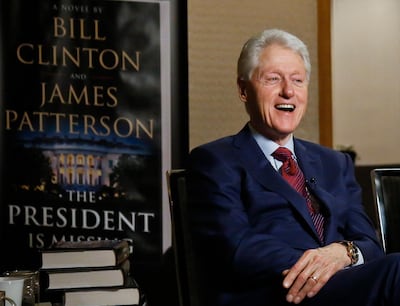

Some politicians have confused "machinations" with outright mendacity. Last year, Bill Clinton, the second US president to be impeached, who has had a complicated relationship with the truth, published a crime novel with James Patterson entitled The President is Missing.

Clinton is a mere dilettante compared to E Howard Hunt, who hit the headlines in 1972 as one of the leading conspirators in the Watergate scandal and cover-up. As well as working for the CIA, Hunt was a prolific novelist under a variety of pseudonyms. Anyone looking for parallels between Hunt the clandestine political plotter and Hunt the narrative plotter need only examine his book titles: Cheat, Counterfeit Kill, Calculated Risk and, best of all, Guilty Knowledge.

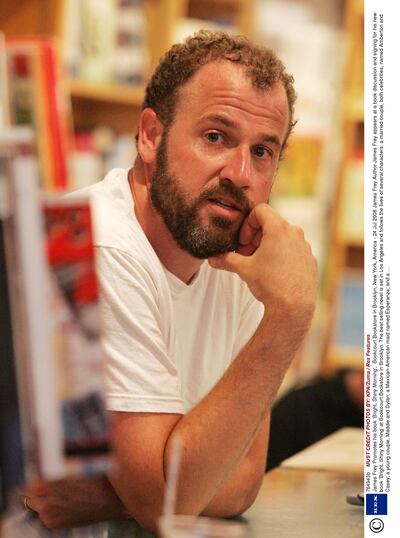

Sometimes it's about more than merely the writer behind a book – often, it's all in the marketing. For example, in 2006, James Frey was outed as a "fraud" when it was revealed that his vastly successful memoir about drug addiction, A Million Little Pieces, was not entirely a matter of fact. Similarly, Norma Khouri's Forbidden Love was marketed as recounting a real love story between Dalia, a young Muslim woman in Jordan, and a Christian soldier, but has since been proved to have been made up.

Frey and Khouri's transgression was to break a fundamental compact between writer and reader. Frey can defend himself by arguing the fictional passages fairly represent the spirit, if not the letter, of his book, but that was not the original deal: A Million Little Pieces, like Forbidden Love, was carefully marketed as telling the (not a) sensational truth.

This delicate, treacherous interchange between art and life lies at the heart of any novel. The most popular questions aimed at writers are: “Where do you get your ideas from? Are you like your characters?”

While sifting an author’s biography for insights into their writing can illuminate, it can just as often mislead (particularly if the writer has used a nom de plume, like J K Rowling, who also writes as Robert Galbraith). Perhaps it all stems from what Neil Gaiman meant by “the obligation to write true things” – an obligation that is “especially important when we are creating tales of people who do not exist in places that never were – to understand that truth is not in what happens but what it tells us about who we are”.

Gaiman explored these ideas in a lecture about the value of public libraries, and condensed them in to one pithy phrase: "Fiction is the lie that tells the truth, after all." Given the slipperiness of this paradox, it seems fitting that Gaiman purloined it from the French philosopher Albert Camus, or at least failed to give him credit. Even this attribution is deliciously treacherous. Camus supposedly coined the phrase in the manuscript of L'Etranger. Or did he? When the page in question was posted on Twitter, no one could find the exact line. And in any case, Pablo Picasso probably coined the aphorism first, when he said (or we're told he said): "L'art est un mensonge qui nous fait comprendre la verite" ("Art is a lie that makes us understand the truth").

Of course, Mallory’s dishonesty was in another ballpark completely. If Ian Parker is correct, Mallory didn’t lie to blur lines separating art from life – he doesn’t know where those lines are, or even if they exist in the first place.

The moral of Mallory's tale has yet to be written. Fresh allegations have since arisen that he plagiarised The Woman in the Window from Sarah A Denzil's Saving April. But so far, falsehood hasn't done him much harm. He rose to the top of his profession, negotiating a vast advance for a novel that became an international bestseller. Now he is more famous than ever. The whole world is talking about Dan Mallory / A J Finn and what he will do next.

According to the New Yorker, his next book is "a story of revenge … involving a female thriller writer and an interviewer who learns of a dark past".

It makes you want to ask: where do these writers get their ideas from?