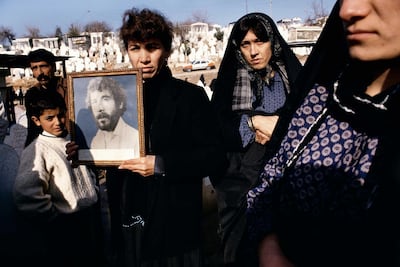

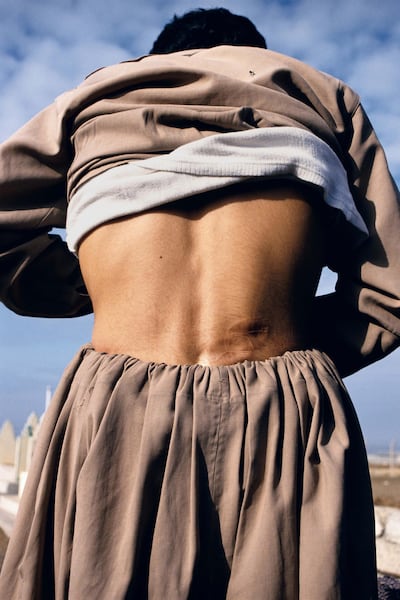

A group of Iraqi Kurds gather on top of a mound of earth. The power in Susan Meiselas’s harrowing photograph is, however, what’s out of the shot. The mass graves of friends and family are in the process of being exhumed. Barely anyone is able to look down. Twenty eight years later, Meiselas can still remember her part in this horrific scene.

"You quietly, patiently wait for the right moment to make the images," she tells The National. "The importance was not finding the bones, actually. It was finding the people who could speak about whose bones they might be.

“So of course that’s private. But these people were around the grave as the exhumations took place for days and weeks. They welcomed the documentation. It was urgent for them to tell their stories.”

From photographer to curator

Little did Meiselas know that her first trip to Kurdistan in 1991 to document the Anfal genocide against the Iraqi Kurds would be the beginning of a career-spanning project to tell those stories. "I changed from being a photographer to a curator," she says of her Kurdistan work, which gathers together testimonies, historical photographs, family albums, projections, maps and illustrated books from the Kurdish diaspora in almost unbearable detail.

It's now showing at The Photographers' Gallery in London as part of her Mediations retrospective, shortlisted for The Deutsche Borse Photography Foundation Prize.

Meiselas, now 70, studied under the peerless American landscape photographer Ansel Adams and shot to fame herself in the 1970s with a fascinating documentary series on everything from the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua to young girls in Manhattan and performers in a risque travelling show. But she is modest about what she was doing as a Magnum photographer back in 1991, drawn to the places from which the Kurds were fleeing.

"It wasn't like I was shining a light on an unknown region," she says. "What took me there was seeing Kurds on the cover of Time magazine and watching the mass exodus from northern Iraq of 180,000 people on CNN.

“But I guess what I felt wasn’t being asked were the circumstances that led to that exodus. I was drawn to the place by the sense that if I was being truthful to myself, I knew nothing about these people or the detail and complexity of the region. I was hearing, but not seeing.”

Creating something bigger

It soon became clear that Meiselas couldn’t just take photographs and leave: there was something much bigger happening in northern Iraq. The task of gathering the collective memory of a suppressed people through photography might have seemed almost too huge to take on, but Meiselas thought it not just possible, but necessary. “What I wanted to do was look at a photograph not as an object, but as something we could re-embed in the history of a people, expanded and anchored by other documents around it,” she explains.

"Then people could dissect and deconstruct, ask not only who was in the photograph, but who made it, what the event was, who saved the photograph. Those are very different questions than just looking at the aesthetics of the shot. It was about making sure a history of a people who don't have a homeland and have no national archive isn't erased."

Workshops with the Kurdish diaspora are still held wherever Meiselas’ Kurdistan exhibition is shown, the archive of documents, images and memories constantly added to. Technology, too, has made it so much easier for people who live within the region to document what is happening, so she no longer feels so compelled to be there herself so often.

"You hear amazing stories of people who worked in carpet factories at six years old, dislocated from their families and home towns. Others tell you about their time in a Turkish jail for nine-and-a-half years. Or of being threatened with deportation despite living in the UK for eight years – and turning that story into an illustrated book."

Showcasing their history to the rest of the world

All of their memories are uploaded on to her akaKurdistan website, but it's the exhibition that is so shocking and moving – a reminder that scrolling through images on a computer or smartphone simply doesn't have the same power as a curated, well thought-out show. "I'm really concerned that, in a world where we see millions of images, people still feel connected through photographs to real people, real lives and the tragedies and difficulties that they face," Meiselas says.

“It’s not the making of a photograph you have to consider, it’s the making of an entire world in which the viewer can experience the lives of others. This is a very difficult task today because we are flooded and saturated – overwhelmed really – with the histories of others, which in reality, we feel pretty disconnected from.

“So what can be still special about an exhibition space is that you take time of a different kind than you do scrolling on your iPhone. Perhaps you connect differently, and if people do that here that’s great. Of course, I also hope the Kurdish community in London have the opportunity to reconnect to their own history.”

As for Meiselas, she’s still enthused by the organic and rewarding process of her 28-year project. She says that Kurdistan as a place continues to exist in the minds of more than twenty million people even though the identification of a state on a map is “way beyond what my work can do”.

So what can it do? “Map a community, in a way. This has all been about acknowledging what the feelings of this community are and what they hold on to. Personally, I wasn’t thinking about taking pictures that might be sold to go on someone’s wall some day. Of course, I was thinking artistically and aesthetically all the time – how could I not. But the best picture can be timely, represent that moment in time … and also last in time.”

The Deutsche Borse Photography Foundation Prize 2019 is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery, London. The winner of the award will be announced on May 16. For more information, visit thephotographersgallery.org.uk and www.akakurdistan.com