On a map of Australia, the Cape York Peninsula looks like a small, wonky witch's hat in the far north-east corner. But up up close, it's a patchwork of wildernesses - coastal dunes, forests, billabong and mountain scenery: a nirvana for nature-lovers. And, if you believe the Aboriginal Dreamtime creation stories, it's all the work of supernatural beings. The first stop on my 16-day trip is the Cape York turtle rescue camp in the Western Cape. To get there I board a turboprop plane and take a short flight from Cairns to Weipa, a mining town. From Weipa to the camp it's a further 90-minute drive north along deserted dirt roads and a bumpy beach track dotted with Pandanus trees, which look like Picasso's version of a palm tree, all skew-whiff and angular. To one side is the Janie River, a playground for crocodiles. The rescue camp is one of the best places in the world to see marine turtles, now an endangered species. The project here is a pioneering one: Aboriginal rangers from the nearby community of Mapoon act as guides to volunteers, and the camp is on land loaned by its indigenous owners. That the Aboriginal elders even have the land to loan is the result of an epic struggle: half a century ago, Mapoon's residents were evicted and their homes burned down to make way for a mining venture. "We weren't consulted and had no time to take our possessions," Danny Cooktown, a local leader, says. A shy, modest man, he explains how his grandmother was involved in the lengthy, but ultimately successful fight to reclaim the township. The camp itself has an agreeably rustic, not-too-polished-feel to it, but the facilities are good. There's a circle of comfortable two-man tents, a shower cubicle that pumps out hot water 24/7 (water is collected from a borehole and heated by solar power) compost toilets and a big mess tent. Here I meet the staff and the other volunteers: there's John and Libby, a middle-aged couple from Queensland, Jeanne, a nature lover from Sydney, and Jaylene, a young biology graduate turned turtle researcher.

All have been here before; that bodes well. Lawry Booth, the camp ranger on duty, is an unexpectedly taciturn chap, but there is no mistaking his passion for the marine turtles. Through him, I learn about their plight: at sea, the turtles become entangled in stray fishing nets, and on land, wild pigs, dingoes and monitor lizards eat the eggs they lay. On Flinders Beach - a whopping 26km long, deserted but starkly beautiful - we watch the giant, gentle creatures nest by moonlight, count hatchlings (in my hands they feel as warm and soft as kid leather), measure the turtles, and in my case, flop on the sand and listen to the crash of waves whilst trying to locate the Southern Cross in the brightest star-filled skies that I've ever see above. In daylight we go bird-spotting, examine animal tracks, ramble in the sand dunes and try bush tucker, such as the woody-woody fruit. One morning Booth leads us to a hidden cove, where we watch two baby crocodiles playing in the water: it's a magical moment. After a night's stay back in Cairns, I meet my driver and guide Russell Boswell, a cheerful Queenslander with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the flora, fauna, people and history of the Cape York region. We travel in a by 4x4 along the Bloomfield Track, which cuts into the Daintree Rainforest, and splashes through creeks and past mountain scenery en route to the Aboriginal community of Wujal Wujal. "The name means many waterfalls - there are no plurals in the Aboriginal language so if something is important it is named twice," Russell says. At the edge of Wujal Wujal, he takes me to meet the Walker sisters, who are members of the Kuku Yalangi tribe. A gentle, close-knit family, they run a fledgling business taking tourists on walks to the Bloomfield Falls. Eileen, her younger sister Kathleen and daughter Gloria lead me up through the forest, pointing out trees and plants that ought to come with a warning: eat too much of the orange finger cherry, and Eileen says, "You'll go blind". Brush up against the stinging leaf, and two years later, you'll still be in agony. Then there's the curious umbrella tree, so called because "If you take a few leaves and burn them when it's raining, the rain will stop." At the Falls the sisters tell me a "Dreamtime story". Alas, I can't repeat it as it's a women's tale, and, tradition dictates, for female ears only. "Stories are an integral part of Aboriginal culture, and have a real currency as traditionally material possessions were negligible. The keeper of a story has a position of status within a traditional community," Russell later explains. Our communion with the falls out of the way, the sisters lay on a picnic. It is a blissful interlude. Back on the road, we embark on a long 4x4 drive inland to Jowalbinna, a safari camp that's in the midst of the famous Quinkan Aboriginal rock art sites. The latter are named after the ancestral spirits said to hide among the rocks. It's entirely fitting then that on the way there, we pass the eerie Black Mountain. Legend has it that those who enter the labyrinth of black granite boulders vanish into thin air. A pit stop at the Lion's Den pub, where menacing, bearded, big-bellied men prop up the bar is spooky in a different way: I venture to the loo, which involves a walk past a room full of pickled snakes, there, as far as I can tell, for no good reason other than to freak out the "sheilas".

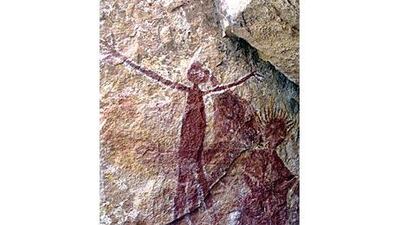

Jowalbinna is in a vast clearing deep in the forest. Behind my bush cabin, to my delight, wallabies hop up and down like mad things. (In the dead of night, the hopping and rustling are less welcome given the tales I'd heard over the campfire, of spirit sightings.) Come sunrise, I'm nearly thrown clear from my bed by the dawn chorus: 55 species of birds have been spotted here, including the blue-faced honeyeater, kukaburra and lorikeet, and every last one, it seems, is determined to deprive me of a lie-in in the nicest possible way. No matter, I'm in the outback, and I love it. After breakfast, I meet Steve Trezise, the son of Percy Trezise, the artist who discovered the rock art sites in the 1960s. Steve is leading a morning hike around them, and we inspect the ochre drawings of animals, spirits, handprints, and stick figures scattered across sandstone boulders and caves in a tree-filled valley. The art, says Steve, dates back 50,000 years and the Aboriginal people who lived in this valley were a community of hunter-gatherers, their lives measured by the rhythm of rituals linked to puberty, manhood, marriage, birth and death. That is until the 19th century when gun-toting miners in search of gold arrived, and a traditional way of life was lost forever. The next day, Russell drives me all the way south to Thala Beach Lodge, outside of Port Douglas. It's a plush five-star lodge, and mangroves, rainforest, beach and woodland are among the habitats within the 60-hectare site. My bungalow overlooks the Coral Sea and the activities on offer include bird-watching, kayaking, nature walks, and star-gazing. I choose the latter - and Rosie the expert uses a laser beam and high-powered telescopes to point out the various constellations. "When Mikhail Gorbachev stayed here, he came star-gazing with his bodyguards," she tells us. Thala makes a great base for snorkelling in the Barrier Reef, but what I enjoyed most was an Aboriginal "Dreamtime Walk", a 90-minute guided hike through a silent, virgin slice of rainforest on a private track in the Mossman Gorge. On the drive there, Harold Tayley, a senior guide who is 55, but looks to be in his late-thirties, owing to "the kangaroo blood my grandfather made me drink when I was a boy" - tells me he's also a healer and tracker who assists the police in locating missing persons. After the walk, over damper (soda bread) and tea, he tells me that he speaks six languages but never went to school. "The white Australian boss on the cattle station where I grew up in the 1960s, and where my parents worked, wouldn't let me go." Desperate to learn, he took to sneaking up outside the school and eavesdropping on lessons. "One day the boss found out and sent me packing," he says. On my last day I visit Kuranda, an artist's colony between Port Douglas and Cairns. In Djurri Dadagal, a newly opened Aboriginal-owned gallery, I chat to artist Lynette Snider. She tells me about her childhood: a familiar story of forcible removal, the struggle to survive, and for her at least, a happy ending - success as an artist and as a mother of eight. It's been almost too much to absorb in two weeks - the staggering landscapes, the wildlife, the painful history and complexity of Aboriginal culture, but the journey has been a unique experience. "You'll be back," says Lynette, "I know it." travel@thenational.ae