Imagine a mid-morning walk among the ancient wonders of Palmyra, Syria. Imagine gazing upon the timeworn walls of the Roman Theatre, the Temple of Bel and the Arch of Triumph as the harsh desert sunlight casts brilliant shadows of columns and pillars, and taking in the splendours of a city that was mentioned in texts in the second millennium BC.

Imagine, too, doing all of the above without actually setting foot in Palmyra itself – and you'll be embracing the technological vision of the California-based The Arc/k Project. The very clever people at the non-profit organisation in Los Angeles have been working to achieve an online database of threatened historical sites since the company was established in 2014.

As the group's online motto elegantly says: "The Arc/k Project digitally archives that which is too valuable, too important, and too unique to be lost or forgotten. As great as the palaces of Versailles or as humble as a discarded arrowhead, our cultural heritage defines who and what we are – and we can all play a vitally important role in preserving it."

Arc/k is the brainchild of writer-director, entrepreneur and philanthropist Brian Pope, a self-confessed science-fiction fanatic, who wants to bring the likes of the Palmyra experience, in the shape of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), to the world.

"I've always had this sense of deep outrage and hurt in the context of something being taken away or lost forever," says Pope, also Arc/k's executive director. "Frankly, it's probably because I grew up on science fiction – and much of the literature I read was rich in the bitterness of lost civilisations and the repetition of humanity's errors and how easy it is to keep repeating mistakes if you don't learn from history. And science fiction is one of the most beautiful genres in which one can tell that bittersweet story."

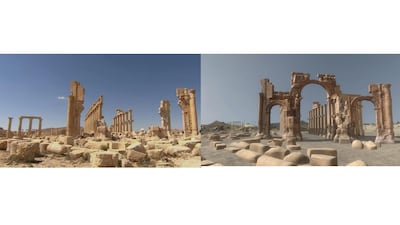

Indeed, like the vast majority of us, Pope watched in horror as ISIS made moves to erase all vestiges of the erstwhile Roman city of the 3rd century empress Zenobia after the extremist group captured Palmyra from Syrian government control in May 2015. Having sent shockwaves around the world by its wanton cruelty against people and its ability to inspire followers to join its ranks from as far afield as the United States, Britain and France, ISIS announced its arrival in Palmyra by destroying those structures which made the ancient city so revered. The best preserved of Palmyra's ancient relics – the 1st century Temple of Bel – was destroyed by ISIS as was the 1,800-year-old Arch of Triumph. The retired 81-year-old director of antiquities in Palmyra, Khaled Al Asaad, a native of the city, was branded an idolator, apostate and heretic and was murdered by ISIS militants after he refused to cooperate with them as they spied other opportunities to destroy more of the city and loot its treasures for sale on the black market.

But while ISIS was driven out by the Russian-backed government forces of Syrian President Bashar Al Assad in March 2016, the group recaptured the Unesco-listed archaeological desert oasis that December and set out to topple the incomplete 2nd century Roman Theatre, which it partially destroyed. After the Syrian army retook Palmyra from ISIS in March 2017, world-leading experts in restoration and archaeology have looked to make sense of the damage.

“The concept of blowing things up on behalf of nationalism or religion or race has been absolutely insane to me since I was four years old,” says Pope. “I was brought up to be a human being first, a citizen of the world second and an American as a very distant third.”

He says the "articulate rage" that had so consumed him after the Taliban destroyed the Buddha statues of Bamiyan in Afghanistan in March 2001 resurfaced after he read of ISIS's attempts to flatten the Syrian citadel, which, in ancient times, was one of the grandest, wealthiest and most culturally diverse places on Earth. Early rulers of Palmyra – which means City of Palm Trees and was a name given to it by its Roman rulers in the 1st century – included the Assyrians and Persians. It evolved into an integral part of the old Silk Route and linked East and West. So, for Pope, deciding on Palmyra for a digital makeover was an easy decision to make.

Arc/k relies exclusively on image crowdsourcing for subjects which have been destroyed. When the organisation was attempting to digitally recreate the three structures in Palmyra, it gathered more than 10,000 images captured by tourists, academics and surveyors between five and 10 years before ISIS arrived.

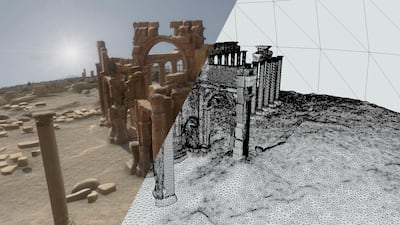

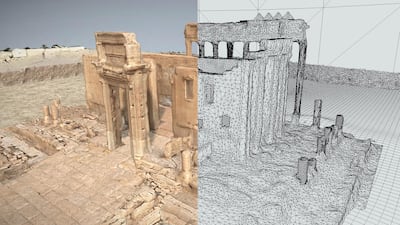

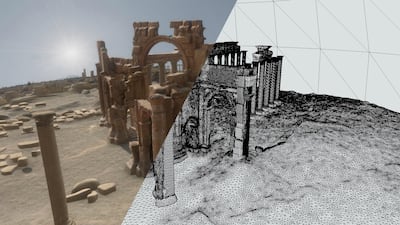

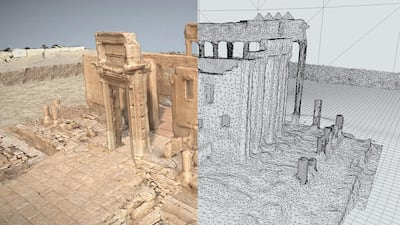

“Instead of accessing and cataloguing the damage, our main focus is on [virtually] salvaging and perpetuating, via crowdsourced photogrammetry, which allows us to go back into the past and capture the site as it was,” says Scott Purdy, Arc/k’s director of operations. “This can be true for any site or object, but happens to be particularly timely for Palmyra.”

Photogrammetry is “a measurement tool and a scientific tool… that allows for a true sense of the texture and geometry of the object, monument or landscape at that time,” says Purdy.

By adopting photogrammetry techniques, the Roman Theatre, the Temple of Bel and the Arch of Triumph suddenly became instantly recognisable structures, and “what existed once in the past [was brought] to a digital realm in the present”.

The role of Arc/k, notes Pope, is not to strive for scientific accuracy to the nearest micro-millimetre, but to make certain that the Palmyras of this world “remain alive in hearts and minds”.

“There is this great moment where the sun is accurately placed for a given day of the year and you can look out under the arch and be blinded by the sun coming across the arch,” says Pope of Arc/k’s VR Palmyra experience. He says it has inspired genuine and very intense emotions among users.

At the heart of The Arc/k Project's digital ethos is a determination to democratise the crowdsourcing initiative. Pope refuses to leave archiving and preservation in the hands of the world's universities and big institutions which, he says, are often hindered by issues of politics, and wants Arc/k to be "both an invaluable resource for and a bit of a thorn in the side of academia".

The organisation, therefore, is attempting to promote the idea of “citizen science” as a means to “generate crowdsourced science as a data-gathering tool”.

“We want to use citizen scientists as data-gathering volunteers to generate results that are so close to what scientists in the field could get, that academics and institutions will no longer be able to ignore citizen scientists as valid data-gatherers,” says Pope.

He and his team believe this is proving successful in Venezuela, where they have mobilised a community of activists remotely without setting foot on the ground. Here, and using video conferencing and instructional films, they have taught individuals to shoot in the style and technique necessary to carry out the data gathering. In collaboration with five Venezuelan museums, archival photos are digitally delivered to Arc/k, which then begins the 3D archiving process.

"These would be art or artefacts from individual collections which [the museums] deem either the most important or the most endangered from potential looting or theft," says Pope, adding that Arc/k has also been concentrating on digitally preserving public art in the South American nation where metal theft of bronze and copper sculptures and monuments is a serious problem.

The team's hope is to replicate the Venezuelan experience elsewhere, not least in the Middle East. The organisation, whose website is available in Arabic, is all too aware that the notion of Westerners – and indeed Americans – designing what is or what is not worthy of preservation in other parts of the world is both disrespectful and counterproductive. Arc/k is therefore keen to one day enthuse like-minded and historically aware individuals across the Arab world. It wants them to take to the streets and digitally capture structures past and present as a means to preserve what might be under threat from destruction or what is simply dear to their own community. "It might be Crusader castles in Lebanon," says Purdy. "But, it might be that capturing Crusader castles isn't what the people think is most important. There are countless other beautiful and culturally important sites in Beirut, too – it's all in the eye of the beholder. The great thing would be to gather all these interested people who have that technology in their hands."

Elsewhere, the organisation has worked with projects in Canada and is also hoping to capture the Schindler House of 1922 – an iconic building on its doorstep in West Hollywood, Los Angeles and the work of Austrian-born American architect Rudolph M Schindler – within the next six months. But Pope and Purdy, despite their past involvement in film production, have no desire to pursue Hollywood or see their creations used in computer games. They see Arc/k as an educational outfit, whose projects will one day be found in museums, cultural institutions and schools across the world for the benefit and education of all.

As for Palmyra, also known as Tadmor in Arabic, Arc/k is hoping to push on to the next phase of its project: to refine the detail and structure of the existing sites and create the city in its entirety to see in one VR experience. Whether or not that happens in the short-term depends largely on funding. But the Arc/k team wants to see this pearl of the desert come alive in people's minds, regardless of whether they visit the real thing.

“All of us at Arc/k are really passionate about phase two [of Palmyra] – and we’ll likely make it happen one way or another,” says Purdy. “We believe strongly in this cause, so it will come down to a matter of when and not if.”

Palmyra, for The Arc/k Project – which Pope has established as a foundation that will allow the organisation to continue long after the executive director’s death – has great global resonance. It has an importance that stretches way beyond its own boundaries, and one that gives hope for a future in which the world’s past in all its glorious technicolour can never be erased.

“We’re not trying to pretend that we’re saving Palmyra – we’re not,” says Purdy. “We’re just putting it in a different medium to show what it was. Our hopeful message is that ISIS can think that they’re creating Year Zero – that this is the beginning of history and everything that came before means nothing – but we can

say, ‘No, not really, you’re not ever going to destroy this’.”