In the early 1990s, when he was in the first stages of assembling his now-vast library, Dubai businessman and philanthropist Juma Al Majid visited the National Library of Morocco. He was hoping to make microfiche copies of the institution's rare manuscripts. The UAE's founding father Sheikh Zayed also happened to be there, visiting King Hassan II, and, according to the story I was told at the Juma Al Majid Centre, he asked how he could help Al Majid in his mission.

Al Majid explained what he wanted access to: everything. Following Sheikh Zayed's request, King Hassan II of Morocco complied.

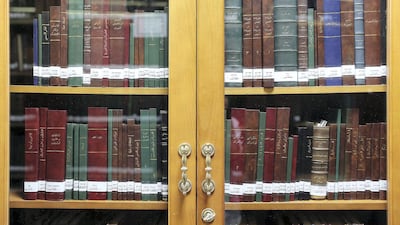

Since that point, the Juma Al Majid Centre for Culture and Heritage has grown to encompass 17,000 original manuscripts and more than a million copies of manuscripts, 400,000 books – many of them personal donations of entire libraries by scholars in the Middle East – and 7,000 journals.

But perhaps as important as what the Juma Al Majid Centre holds is what it enables access to: it is digitising its entire contents, in order to distribute copies of the books and manuscripts to scholars either at the centre or by email. And it has brokered 120 bilateral agreements with libraries around the world, under which it donates specialist equipment for restoring manuscripts to each library. In return, it is allowed to digitise their manuscripts and hold the copies in Dubai.

The idea that information is free, at play in a field of brittle, fibrous paper, is a very 21st century one. “Nobody has a right to say, ‘This book belongs to me.’ It belongs to the human,” Al Majid says. “Put it on the internet. Let people read it in China, in South America, in Russia, in Europe.”

These bilateral agreements mean the centre has become a site for scholars wishing to access a range of manuscripts, most of which have been scattered around the world.

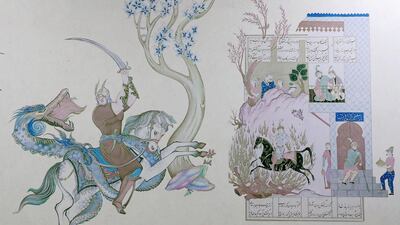

“For those of us who research the pre-modern Islamic world, we’re very dependent on manuscripts,” says Justin Stearns, an associate professor of Arab Crossroads Studies at New York University Abu Dhabi. He researches the interrelation between science and the discourses of law, theology and Sufism in 17th-century Morocco. “The vast majority of things ever written are still on manuscripts. They have not been edited and printed. And the scary thing is, we’re still in the process of cataloguing. In many cases the catalogues of these libraries are not up to date or are faulty.”

Based in Deira, Dubai, the centre is situated close to the airport. Planes buzz low overhead, casting large shadows on the ground. In the digitisation room, copiers are at work at 11 desks, aiming for a target of 2,000 pages a day. Klieg lights illuminate each glass-topped machine, while workers take and return books from the wheeled carts next to them. The room, though stuffy with the heat of bodies and activity, hums with purpose.

In the manuscripts room, kept under lock and key, the centre has made bespoke boxes for each of the papers, which vary in size. Each box is checked around every six months for any fungal or bacterial infection, which can spread from manuscript to manuscript. If they are infected, they are treated by machines that the centre invented, located in an offsite factory, which sterilise manuscripts, restore paper fragments and retouch the writing, working on numerous pages at once.

Al Majid, now 87, has an office on-site where he meets and greets visitors to the library. Al Majid made his fortune in business – through dealerships for Isuzu, Hyundai, Citizen Watches and Samsung home appliances, among others – and set up not only the library, but also the Beit Al Khair Society, which funds social welfare projects and has an education arm.

__________________________

Read more:

Juma Al Majid named ‘UNHCR Humanitarian Champion’

Juma Al Majid takes over running of Taj Palace in Dubai

__________________________

He was one of the first philanthropists to set up universities in the UAE, including one specifically for women, so that Emiratis could study while still remaining at home (many parents at the time didn’t want their daughters to travel or live away from home).

Although Al Majid has established one of the largest libraries in the Middle East, he jokes that he is not an educated man. “I don’t even have a primary certificate,” he says. But he is committed to the idea that, as he says, “education is not about money”.

“Who can travel from China to Oxford to see one book? Everyone must work for the book to travel to the researcher and not the researcher to travel for the book.”