Fahim, three, and Narges*, two, are playing in the courtyard of their family home when their father walks in, an AK-47 slung over his shoulder.

His face is barely visible under a tightly wrapped bandana – the “Taliban burqa,” he jokes later, referring to the traditional gown often worn in rural Afghanistan that covers women from head to toe.

The children come running excitedly as Qary Khalid bends down to hug them with one arm, their colourful clothes pressed against his white tunic, his left hand holding on to the weapon.

Khalid is a Taliban commander, but at home, the 25-year-old is a father, not a fighter. In his village deep in a Taliban area, he is well respected as one of the group’s local leaders and everyone knows his son and daughter.

Fahim and Narges’s reality – a fighter father – is shared by thousands of children in Afghanistan amid an increasingly deadly war for non-combatants. The UN said 927 boys and girls were killed in 2018, the highest number of child deaths in a single year since it began recording casualties in 2009.

Many families, including those of Taliban fighters, have left the country for just this reason over past decades. The Afghan refugee population of 2.5 million is the world’s second largest, surpassed only by Syria.

Khalid's family lives in a small brick house near the bazaar of a farming village in eastern Afghanistan, reached by dirt roads lined with tall trees and green fields of growing wheat. Along the main road, shaggy-haired Talibs with long beards set up frequent checkpoints, controlling who comes in and out of their territory. None of the group’s white flags have been put up.

“It’s the front line and we’re afraid of US-surveillance,” Khalid says. “If they find anything, they might attack.” The fighter has no alternative but to stay here, the village he grew up in. “It’s home,” he says, but admits that the fear sits deep, especially at night, especially for his children.

“It’s dangerous for them," he says. “Last year, our compound was raided by the government and seven people were killed. At night, we hear the drones fly above our houses. An air strike hit close-by last week.”

But the man with warm, dark brown eyes and a short-trimmed beard says there is little alternative; he has to fight both the foreign-backed government and the “infidel invaders”.

And if it was not for his job and the weapons stored in his house, the family’s life would look little out of the ordinary. Khalid’s house is cosy, with a tree shading the courtyard where his wife sits on a small rug chatting with neighbours, sewing small beads on to a silky scarf.

The son of an aid worker, Khalid joined the Taliban 10 years ago, when he was still a child himself, after attending a madrassa – a religious school – in Peshawar, Pakistan. For the past four years, he has worked as a group commander, planning and carrying out terrorist attacks and helping to mobilise new recruits.

Having his own children join the militant group later is however out of the question for the young fighter.

“The biggest change I’ve seen in the Taliban is a quest for education, and that’s what I want for my children," he says. "As for me, I will fight. This is not the war of the Afghan people, it’s a foreign war. If they decide to finish this conflict, they will. We can fight, but we can’t end the war.”

The Taliban and the United States have been holding talks on a peace deal, but little progress has been made in recent months. The Afghan administration has been largely left out. Despite the talks, the Taliban have continued – even increased – deadly attacks across the country.

And while the war rages, many of the Taliban’s children live a double life.

At his school in north-east Afghanistan, 11-year-old Adeel pretends to be the son of a local businessman; at home, he is the child of a commander in the Taliban who has close ties with Al Qaeda. His family lives undercover in a government-controlled area.

“I was born in Swat Valley in Pakistan, but I can’t go back. Our family would be killed,” Adeel explains matter-of-factly, sitting on a cushion next to his father, a slim man with an infectious white-toothed smile.

The living room they sit in is largely empty, with big windows on two sides and only an old laptop resting in a corner. None of the Taliban commander’s meetings are held here, ensuring their home remains a safe space for Adeel and his four siblings.

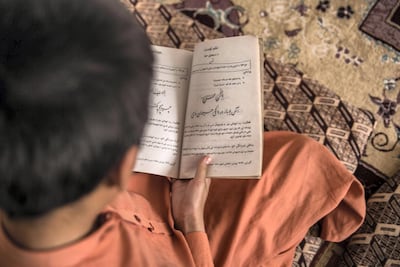

Like most people in his village, Adeel speaks Pashto, and with his orange shalwar kameez and his rusty bicycle that he rides to school every day, he blends in perfectly. Nobody in the town knows that he is not Afghan. Nobody knows about the weapons his father hoards or the secret meetings he attends regularly.

“During cricket matches, I cheer for Afghanistan with my friends, but for Pakistan at home,” he grins.

Yet his secret is not always easy to keep. Adeel often worries about his father and misses his extended family, wishing he was not different from the other boys in class.

“Grandma came to visit four years ago,” he says. “We went for walks and played games and Dad was with us the whole time.”

His father’s frequent absences make the sixth-grader uneasy. “I know he fights and kills. He says he does it for our people,” says Adeel, who wants to become a doctor to help people in a different way.

At school, he learns that the Taliban is bad and the government good, while he hears the opposite at home. Adeel has made it easy for himself. “I like them both,” he says.

He enjoys English classes the most. “It’s my favourite subject because it’s an international language,” he says, shifting on his cushion.

“I don’t like fighting,” he explains. “I want to build relationships even with the foreigners. If I learn English well, I can speak to them and get to know them well.”

* Names in this story have been changed to protect the children's identity.