Growing tensions between the United States and Turkey regarding the campaign against ISIL in Syria and Iraq reveal significant weaknesses in the current American approach, and where it will have to change course if it is to succeed. American officials have been critical of Turkey for not intervening against ISIL on the ground as the United States and some of its other allies have been doing in the air.

Turkey's most significant demurral is that it will not be drawn into Syria as part of the new American coalition against ISIL unless there is an explicit understanding that one of the key goals of intervention in Syria is the downfall of the dictator Bashar Al Assad.

The present American approach – which is limited to a multiyear effort to “degrade and destroy” ISIL – cannot function without more substance, given that other key forces in the Middle East, especially those that might serve as ground troops backing up air strikes, won’t be satisfied with signing onto that limited goal without any further elaboration.

The Turks are hardly alone in finding the present American approach less than inspiring and lacking in answers to key questions, especially about the future of the Assad regime. But the impression that the US has been drawn into conflict with ISIL because of Iraq – and that Syria is an unavoidable addendum but not a major concern – remains essentially correct.

There’s little doubt that if the Obama administration could have found a way to combat ISIL meaningfully with air raids in Iraq only, it would surely have done so. It could not, and therefore it is striking inside Syria. But the future of Syria is not a key factor – or has not even really been accounted for – in the evolving American strategy so far.

The familiar American concerns about Syria that have held it back from playing a major role in that conflict since its outbreak remain strongly held in the administration. Some senior American officials still argue that while Mr Al Assad must go, existing Syrian state institutions must stay because chaos is the only alternative. Critics note that, in practice, this inevitability ends up looking like an oxymoron that defaults to regime survival.

Moreover, the deep-seated American belief – that there are no forces on the ground that can be trusted with major funding and arming, and that the international community lacks any real “good options” in Syria – also persists.

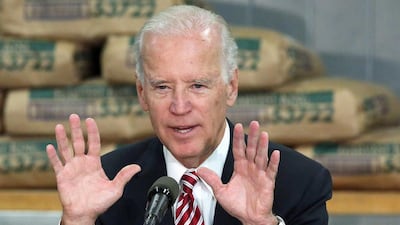

Vice president Joe Biden recently found himself embroiled in controversy following remarks in which he vaguely accused a raft of different American allies in the Middle East of funding and arming extremist groups. Mr Biden’s remarks were too jumbled to constitute a strong or specific bill of particulars against any of the states he named.

But there was an unconscious and ironic aspect of self-criticism in his comments as well. For years, many Americans warned in vain that if the US did not engage in backing some opposition forces in Syria, thereby helping to shape the nature of the conflict and the identity of its participants, others would – and not necessarily in a manner pleasing to Washington. Mr Biden seemed to be suggesting that this is exactly what happened, but without recognising that his own administration contributed to whatever dynamic displeased him so much by doing nothing for so long, and thus consciously ceding the field to others.

The situation in Syria has deteriorated to the point where it may now be true that there are very few extant forces seriously engaged in the conflict with which the US can reasonably consider partnering. Yet the Turkish reaction to an American policy that is clear that ISIL must go, but highly ambivalent about the future of Mr Al Assad, will be shared by most American allies in the region and all serious potential local forces that could emerge as the ground troop vanguard against ISIL in Syria.

So now the United States may be faced with trying to create a new constituency or force on the ground rather than win an existing one over, as it could well have done a few years ago. But the reality is that, just as the war against ISIL could not be limited to Iraq, it must also have clear goals about the future of Syria beyond it being a battleground with terrorists.

Like it or not – and the Obama administration is not going to like it much – one way or another, and sooner rather than later, the United States is going to have to make the replacement of Mr Al Assad an explicit goal of its intervention in Syria. Otherwise, not only will Turkey stay out of the fight, no plausible local forces will sign up for the task either. And the entire enterprise will fail.

That’s not an option. So, against all the administration’s instincts, an American policy shift against Mr Al Assad is a matter of time.

From the outset of the Syrian conflict, it was inevitable that the US would eventually get drawn in to it. Now that it has been, there is now no way it can avoid – or even postpone much longer – committing itself to the goal of ending the Assad dictatorship.

Hussein Ibish is a senior fellow at the American Task Force on Palestine

On Twitter: @Ibishblog