Mudar El Sheikh Ahmad did not take his love for Syrian food seriously until he fled the country more than four years ago. His adoptive nation, Germany, was very welcoming, but finding an authentic Syrian meal there? "Nah, it is difficult to find, even in Berlin," says Ahmad of the multicultural capital where he lives. "What I find in Syrian restaurants here is street food," he says, which does not define the country's culinary offering in its entirety.

In the beginning, Ahmad's calls to his mother in Aleppo were full of questions about recipes. He furiously took notes about preparations for delicacies he missed the most and wanted to try in his kitchen, such as mahshi (veggies stuffed with rice) and the aromatic dessert layali lubnan.

Once Ahmad had perfected the recipes, he started inviting his neighbours over for meals. "They loved Syrian food and my cooking," he beams. Most importantly, he discovered that getting people together over meals gave them a platform to find new friends and have interesting conversations. At the end of the evening, almost everyone thanked him not only for the food, but also for bringing them together.

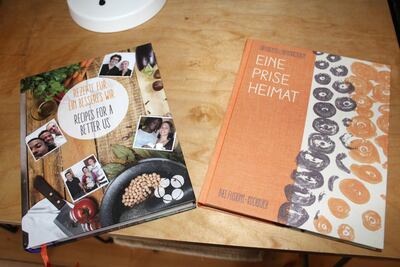

One year later, Ahmad received an invitation to attend a community cooking session from Uber den Tellerrand, a non-profit headquartered in Berlin that works to integrate "people on the move" in German society. It takes its name from an expression that translates to "beyond the edge of my plate", and the organisation's activities include bringing locals and refugees together to share meals in 30 cities in and around Germany.

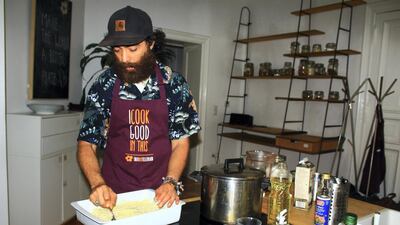

Ahmad found a match for his own philosophy in Uber den Tellerrand. Soon, he was volunteering to organise community cooking sessions and cooking workshops to demonstrate Syrian recipes to diverse groups of people. Today, he works for the company part-time and conducts three to seven sessions every month, which is a long way from being an Arabic teacher in Aleppo.

“For the sessions, people drop in with an open mind and a curiosity to learn something new,” says Julia Groos, Über den Tellerrand’s cordinator for Cologne. And she thinks that the experiences are especially satisfying for the refugee chefs because “they switch roles; they’re no more the ones who take, but the ones who give and share”.

Angela Merkel: We can do it

In 2015, Germany's chancellor Angela Merkel opened up the borders to refugees with the assertion "wir schaffen das", meaning "we can do it", and went on to cite Germany as a "strong country". More than one million people received asylum in Germany by the end of 2018 – of which half are from Syria alone – according to the United Nations' Global Trends report. The numbers are the highest for any European country.

Merkel's idea, however, wasn't simply to offer asylum seekers protection or a safe place to live. A historic integration law was introduced in July 2016 to facilitate language courses and education for their absorption into the job market. Between 2015 and 2016, 15,000 integration projects were launched across the country with the intention to help newcomers to learn the language and understand the culture. In such a conducive environment, it is relatively easy for organisations such as Uber den Tellerrand to thrive, especially since funding is not difficult to come by.

Start with a Friend

The most difficult thing when you move to a new country is to find friends," says Hassan Al Ramahi, a machine technician who fled from Baghdad and now studies in the University of Cologne. When he arrived, he could speak Arabic and English, and had to make extra time to attain speaking proficiency in German through the mandatory language course he was pursuing. "It is crucial to know the language to make friends," he says.

Signing up to Start with a Friend (SWAF), an organisation that connects locals with the newcomers in tandem partnerships, helped. Al Ramahi found a like-minded German partner in Cologne, and the duo hung out together at cafes and cinemas. "It is essential to have someone guide you through the city," Al Ramahi says.

Recently, SWAF asked him if he would like to conduct a community cooking session for Uber den Tellerrand. "I thought, why not? It would give me a chance to be a chef for one evening and I can cook my favourite cuisine," he says. His dish of choice for a group of 20 was timman bagila (fava beans with rice) and marqat baytinijan (aubergine stew).

Al Ramahi thoroughly enjoyed the experience. “For once, I wasn’t cooking alone; there were so many who helped me. The food was a result of teamwork.” He was also somewhat floored by the way the room turned silent once everyone served themselves and dug into the food he cooked.

Majed Al Saaed, who is from Syria and attending high school in Germany, has been a part of such community sessions at least eight times in Cologne. "I've met Syrians, Germans and people from other cultures and made so many friends," he says.

"Right now, I can see at least 10 people I'm keen to get to know from this group," interjects fellow Syrian Bilal, who goes by one name. "The food is delicious, people are wonderful and we have so much fun. I'm really bad at cooking, so I prefer to help and focus on eating," he says, with a laugh, adding that he's been to 10 sessions so far.

Katharina Neiss, who works for a non-profit for the integration of refugees, says of her first session: “I like that everyone is so easy-going here. I got to know so many new, amazing people.”

Trials and triumphs

Life is easier for refugees in west Germany, but the prevalence of the right-wing party Alternative for Deutschland in the eastern states blights the country's image of being accepting of refugees. Recently, the party, which is against Merkel's migration and refugee policies, and wishes to close the country's borders, surged by a higher margin in September's state elections in the eastern states of Saxony and Brandenburg to stand at the second position in both states. And refugees have felt the risk.

Fadi Zghaib, who fled from Damascus about four years ago, says he feared for his life when he was in a refugee camp in Dresden, the capital of Saxony. “There were frequent demonstrations by far-right activists in the city, and I was stared at when I walked the streets,” he says.

His fear dissipated when he moved to Cologne, and he got a taste of German hospitality when a couple gave him a room to stay in their home for five months and every possible help in processing his papers for asylum. However, he still finds it difficult to make friends with Germans, in the absence of good language skills and differences in culture. The cooking sessions at Uber den Tellerrand help Zghaib to practise his German, make friends and be inspired by the stories of fellow refugees who have integrated successfully.

Ahmad, for instance, had his parents move to Berlin last year. "There is a big Arab community here, so they feel comfortable," he says. And does he like Berlin? "I like it a bit too much," he grins. Last week, he opened a restaurant in Berlin's Kreuzberg neighbourhood. "If it is successful, I don't think I will ever go back."

This story was supported by a fellowship from the Robert Bosch Foundation.