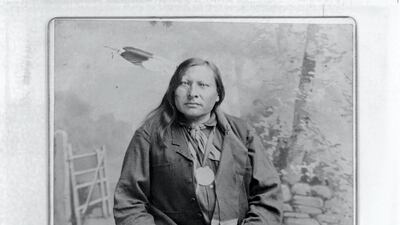

The massacre mentioned in the title of David Treuer's new book, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee, took place in 1890, in the middle of a harsh South Dakota winter. Spotted Elk, the leader of a band of Lakota Sioux that numbered around 350, was taking his people to a sanctuary called Pine Ridge when, on December 28, they were stopped by a detachment of the United States Seventh Cavalry and diverted to a campsite on Wounded Knee Creek.

Before dawn the following day, soldiers set up four cannons around the Sioux and moved into the camp to confiscate any weapons they could find. A young Sioux man fought back, and soon other young warriors joined in as a short, pointed catastrophe ensued.

The soldiers opened fire, the cannons roared, and although the Sioux men tried to fight back, they were mowed down, alongside quite a few soldiers caught in the crossfire. Indeed, as Treuer points out, it was one of the worst cases of friendly fire in US military history. The women and children who fled along the frozen creek bed. were chased down by mounted cavalrymen and killed. After

an hour, 150 Lakota Sioux were dead.

It was just one incident on a long, long list of deadly encounters between Native Americans and the US military, and yet the events at Wounded Knee quickly took on a symbolic weight that was not given to similar incidents. Sympathisers to the cause of Native American welfare condemned the Wounded Knee massacre, while their opponents characterised it as self-defence (or far more racist interpretations), but Treuer says that its significance went beyond the killing.

"Both sides joined in seeing the massacre as the end not just of the Indians who had died, but of 'the Indian' period," he writes in the book. "There had been an Indian past, and, overnight, there lay ahead only an American future."

Even later sympathisers, such as Dee Brown in his seminal book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, published in 1970, tended to follow this general model. It is at the heart of Naomi Schaefer Riley's shattering 2016 book The New Trail of Tears, for example.

Treuer, recalling his own childhood in the Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota, evoked beautifully in his book Rez Life, considers his book a "counternarrative" to this view, coming to see his reservation as a bleak place "where nothing happened and good ideas went to die".

Despite this strong urge to counternarrative, a great deal of The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee looks to the past before it shifts its focus to the present or the future. Treuer ranges his inquiry back to Christopher Columbus, draws it forward through dozens of first encounters that result in depredations, and recounts the iniquities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, especially dating from the end of the Plains Indian Wars in the 1880s and the consequent explosion in the influence of the Office of Indian Affairs.

This was the era of Senator Henry Dawes, who infamously said that the US wanted its Native Americans to wear western-style clothes, farm the groun and drive Studebaker wagons … the era of Indian affairs commissioner Thomas Morgan, who flatly stated: "It has become the settled policy of the government to break up reservations, destroy tribal relations, settle Indians upon their own homesteads, incorporate them into the national life, and deal with them not as nations or tribes or bands, but as individual citizens."

Emblematic of the 19th century version of this was Richard Henry Pratt's Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where in 1879, Indian children were "civilised" – that meant they were forced to wear Western clothing, forbidden to speak their own languages, and made to shave their heads. "For the Lakota to cut one's hair was a sign of mourning, so when the barber commenced there was loud ritual (and heartfelt) wailing," Treuer writes in his book.

Despite hundreds of pages documenting these kinds of travesties, Treuer's book has a bright, upward arc. Slowly at first but gaining force in the book's final quarter, the story begins to fill with hope. From organisations like the American Indian Movement, that rose in 1968, to the present day, this part of the book tells Indian histories in ways that culminate in more than "a catalogue of pain". Treuer says that he has tried to catch the Native American world "not in the act of dying, but in the radical act of living."

As he says, the picture is improving slowly. Native American income is growing; poverty rates are dropping; Native American-owned businesses are growing; and their college enrollment is booming.

Shortly before the US edition of Treuer's book was published, the first Native American women were elected to Congress in November. The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee has many tragedies to recount, but it ends on a hopeful note.