Over the past 10 years, climate change has become an increasingly important topic for policymakers to tackle. Around the world, governments have started recognising the need to place the issue at the forefront of the political agenda, introducing policies to safeguard the environment.

Sweden, Costa Rica, Germany and Denmark have led the charge, with Copenhagen set to become the world’s first carbon neutral city in 2025.

And yet, scientists say these measures have not gone far enough. The world is still on track to warm three degrees Celsius by the end of the century. Air pollution is growing ever-worse, with bad air quality linked to 10,000 deaths in the US in the space of two years, India declaring a public emergency in Delhi due to toxic smog, and pollution halting flights, closing roads and stopping construction in Shanghai.

Extreme weather events – from drought and wildfire to floods – are hitting international headlines with alarming regularity.

So as we come to the end of one critical decade for climate change, what needs to happen over the coming one to make – or break – climate change reform? The National asked the experts.

Businesses must take responsibility

It’s “imperative” businesses take action, says Dr Liz O'Driscoll, managing director at Exeter City Futures, an initiative working with business to turn the UK’s city of Exeter carbon neutral.

The relationship between business and climate change policies is an intricate one, with lobbyists fighting for fewer restrictions on waste, carbon footprints and recycling.

Dr O’Driscoll says temperature changes will slow economic growth, and so businesses have a stake in ensuring global warming is curbed.

“Behind those big numbers are trillions of businesses, and each one of them will contribute to or slow down climate change based on their decisions.

“Businesses cannot wait for governments and legislation to catch up with the predicted impact of climate change,” Dr O’Driscoll continues, adding taking a proactive approach and going beyond policy expectations of governments will influence consumer choices, and result in a substantial positive impact on the climate.

Politicians need to be braver

Climate reform will depend on breaking up the political power held by companies that profit by keeping unsustainable systems in place, such as the fossil fuel industry, says Marie Claire Brisbois, a professor in energy policy at the UK’s University of Sussex. And this will only happen from the bottom up.

“Shifting power at national levels depends on public actions at local levels,” Professor Brisbois explains. “Citizen movements for rights to own and sell distributed energy, repair and reuse products, and grow and consume local food are a big part of building new systems that provide essential services.”

Professor Brisbois says these new systems are crucial in building a better world as they prioritise values beyond profit, “and, in the process, chip away at the corporate capture of governments”.

The way we eat needs to change

The way we grow, process, distribute, eat, and dispose of food contributes to climate change, and climate change affects the future sustainability, security, and equity of the food system.

“Fortunately, our food systems can be transformed to provide the climate solutions we urgently need,” says Ruth Richardson, executive director of the Global Alliance for the Future of Food. Changes such as increasing homogeneity in agriculture, moving away from pesticides, better control of fish stocks and developing high-yielding, drought-tolerant crops that require less land and water to grow are all examples of how food systems can be more climate-friendly.

Ms Richardson adds that food system transformation requires sectors working together on issues such as antibiotic use, animal waste, emerging diseases and food safety.

“By adopting a food systems lens, policymakers can go beyond limited and siloed interventions that carry unintended consequences.

“Simply continuing to rely on ‘business as usual’ approaches and models will have severe negative impacts environmentally, socially and economically,” she adds, citing everything from increased biodiversity loss and soil erosion, to the decline of rural economies, to an increase in migration and market volatility.

Where and how we live needs an overhaul

Cities play a huge role in determining the future of climate change, considering their large share of the global population and energy footprint. More than half (55 per cent) of the world’s population live in urban areas, according to the UN, which expects the number to rise to 68 per cent by 2050. As of 2018, the urban population numbered 4.2 billion.

“There are many ways that urban planning can reduce the impacts of global climate change,” says Gabriel Filippelli, Professor of Earth Sciences at Indiana University. He cites developing efficient, non-fossil fuel mass transport and centralised heating and cooling systems as being some of those reduction techniques.

“But perhaps the most immediate impacts are seen when cities plan a certain percent of green infrastructure, including urban forests and tree zones,” he continues. “These not only absorb carbon, but also reduce storm water discharges, reduce air pollution and urban heat islands, and enhance health and well being of city dwellers.”

Cities occupy just 2 per cent of the world's landmass. But in terms of climate impact, they leave an enormous footprint, consuming more than two thirds of the world's energy and accounting for more than 70 per cent of global CO2 emissions, and so developing greener cities is paramount.

Give those on the frontline a voice

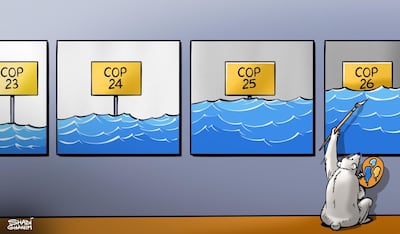

Those fighting climate change on their doorstep are often the ones with the least opportunity to participate in policymaking. The move of COP25 from Chile to Spain saw indigenous voices left out of the climate conversation. Kera O'Reagan, who works for the International Indigenous Peoples' Forum on Climate Change, says indigenous communities are not only on the frontline of impacts, but also solutions – a recent study revealed indigenous land, which makes up around 25 per cent of the planet's land area, contains more biodiversity compared to non-indigenous land.

“Communities like indigenous peoples are routinely ignored, despite being the most affected by climate change.

“They are already doing the work at home to rebalance our relationship with the land, seas, and wider natural world with great success,” she continues. “So imagine what would be possible if we had institutional support or if these approaches and world views were reflected in global political decision making.”

Not only are these vulnerable groups impacted as a result of emissions from the Western world – developed nations typically have high CO2 emissions per capita – but their suffering is having a knock-on impact on the rest of the world, as they flee their now inhabitable homes.

Even if the world achieves all this, we’re not in the clear

There is no fast answer, Alice Bell, director of UK-based climate charity Possible, says. “The truth is that we need to be acting on multiple fronts, at once, we haven’t got time for them to line up in order.

“There isn’t ‘just one thing’ anyone can do to fight climate change – whether you’re thinking in terms of an individual concerned citizen or political leader – we’ve left it so long that we now need to do all the things, in all the places, in all the ways.”

Ms Bell does, however, highlight the importance of public engagement in shaping policy.

“We need more resources put into the hands of local communities for bottom-up work, putting them in the driving seat and providing opportunities for people to come together to take practical, ambitious action on climate change rather than fight over it.”