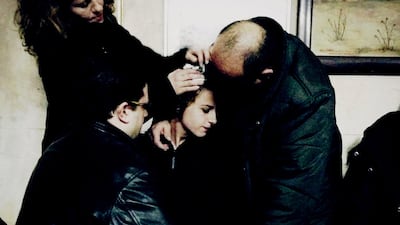

The winner of the best documentary prize at this month's 73rd Venice Film Festival was Libera Nos (Latin for "Deliver us"), a film about the practice of exorcism in modern-day Sicily. Apparently exorcism is enjoying something of a popular revival in parts of Europe and North America.

In his book, American Exorcism, sociologist Michael Curneo says that "exorcism is more readily available today in the United States than perhaps ever before". The United Kingdom, Spain and Italy also report a dramatic rise in the number of people seeking exorcisms. In 1991, the International Association of Exorcists had just 12 members. Today it boasts more than 300 from across 30 countries. In 2014, the organisation was finally granted official status by the Vatican. What is behind the revival of this antiquated practice?

Some commentators have attributed the increasing demand to what they call the "Pope Francis effect", suggesting that the pontiff's characteristically demon-themed style of rhetoric has reawakened people's fear of the devil in general and demonic possession in particular. Others point to the growing acceptance of the occult within popular culture, epitomised by television shows like True Blood, and books such as the Harry Potter series. Of course, the internet also gets a mention, blamed for disseminating knowledge of occult practices such as the Ouija and strange games such as "Charlie Charlie", which encourages children to commune with unseen forces.

In the UAE it is hard to say with certainty if the practice of exorcism (istikhraaj) is any more or less popular than before. However, as in other Muslim nations, the phenomenon of exorcism is well known and continues to be routinely practised.

In one of our research team's recent studies, published in the journal Mental Health, Religion and Culture, we interviewed 10 traditional healers who were regularly involved in exorcisms. All of them assured us that they had never been busier.

There is a rich regional literature concerning unseen beings that are believed, by some, to interfere (malmoos) with and even take possession of (malboos) people. Referred to as the Jinn, these creatures are viewed as one possible cause for abnormal moods and behaviour among the afflicted.

Critics of exorcism argue that the exorcist is often preying on, and reinforcing, the vulnerability of people experiencing psychiatric disorders. Instead of medication or evidence-based therapy they argue, the patient receives a kind of ritualised hocus-pocus that only serves to further confirm their delusions.

The exorcists in the UAE who we interviewed argue that there is a clear difference between the possessed and those with mental health problems. This might be the case, but I don’t know many mental health professionals who can, or do, make the same distinction.

However, despite the availability of modern mental health care services, many people – perhaps even an increasing number of people – are seeking the services of exorcists.

One of the major problems with consulting an exorcist is that, generally speaking, they tend to be individuals with low levels of professional accountability.

Every now and then we read about cases where an exorcism goes horrifically wrong and someone, usually the possessed, usually a young girl, ends up dead. But how many more cases don’t make the news? I refer to those cases that end with individuals being psychologically rather than physically damaged.

Botched back-room exorcisms are a reality that need to be addressed. Furthermore, if exorcism is on the rise, then there is an even greater need to ensure the integrity and qualifications of those performing the service.

This is the only way to protect the often vulnerable individuals electing to undergo such metaphysical procedures.

Dr Justin Thomas is an associate professor at Zayed University

On Twitter: @DrJustinThomas