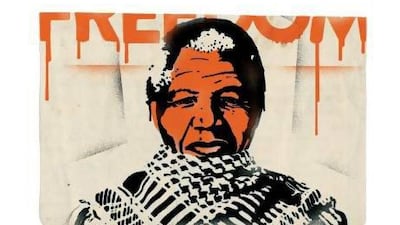

As the world has reflected on Nelson Mandela's legacy and his fight against apartheid in South Africa, some have recalled his famous observation: "We know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians."

That special bond between two peoples and their national struggles has in recent times contributed to increasing South African efforts to challenge continuing Israeli human-rights abuses and systematic discrimination.

A few weeks ago, the outgoing South African ambassador to Israel used the opportunity of his departure to make striking criticism of Israeli policies, calling them a "replication of apartheid". Ismail Coovadia also rejected a gift of 18 trees planted in his name by the Jewish National Fund, a body that has played an important role in the displacement of Palestinians.

Not many countries find ambassadors talking of their policies in terms of apartheid, but coming from a senior South African diplomat, the charge stings all the more. It is a reflection of how South African politicians and civil society have increasingly embraced solidarity with Palestinians and taken the lead with regards to Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS)-related initiatives.

Pretoria has required the labelling of settlement goods, despite significant pressure not to do so, while there have also been notable expressions of support for the Palestinian boycott call in universities and trade unions.

These developments come as Israeli policies towards the Palestinians are increasingly talked about in terms of apartheid by observers on the ground and internationally.

In South Africa, there is the memory of Israel's historic relationship with the apartheid regime (a superb reference point for which is Sasha Polakow-Suransky's The Unspoken Alliance: Israel's Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa).

Israel's warm ties with the apartheid regime began in earnest in the mid-1970s, with military technology and intelligence-sharing central to the alliance. For some officials on both sides, there was also an ideological component. The South African prime minister, Hendrik Verwoerd, for example, believed that "the Jews took Israel from the Arabs after the Arabs had lived there for 1,000 years. Israel, like South Africa, is an apartheid state".

Over a period of about 15 years, examples of the close relationship included a 1975 pact signed by Shimon Peres and then-South African defence minister PW Botha, while in the mid-1980s, the Israeli defence industry was helping the isolated apartheid regime circumvent international sanctions. Israel's "collaboration with the racist regime of South Africa" was condemned in the UN's General Assembly.

Yet what has really struck many in South Africa, and elsewhere, are the similarities between the historical apartheid system, and Israel's current policies towards the Palestinians.

In 2002, Archbishop Desmond Tutu wrote an article called Apartheid in the Holy Land, saying that his recent trip to Palestine/Israel had reminded him "so much of what happened to us black people in South Africa". In 2007, the UN Human Rights Rapporteur John Dugard, a South African legal professor and apartheid expert, said that "Israel's laws and practices" in the Occupied Territories "certainly resemble aspects of apartheid".

The common element of both systems is the consolidation and enforcement of dispossession, securing control of and access to land and natural resources for one group at the expense of another. Yet there are also important differences.

While the apartheid system required the labour of black South Africans, Zionist settlement in Palestine viewed the local non-Jewish population very differently: as a group to be expelled rather than exploited. The reason why there is today, inside Israel's pre-1967 borders, a clear Jewish majority is because the majority of Palestinians who would have been citizens of the new state were ethnically cleansed, their villages destroyed, and their land expropriated.

Though there are numerous examples of de facto segregation and institutionalised discrimination within pre-1967 Israel, the apartheid comparison really began to take hold as Israel expanded its colonisation and control of the Occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Apartheid was, in a way, "Plan B": a way of maintaining Jewish hegemony and control - protecting the ethnocracy - when outright, mass expulsion was not feasible.

An Israeli academic, Oren Yiftachel, has described the situation in Israel and the Occupied Territories - speaking of them as a single unit - as a "creeping apartheid", in the sense that over time a de facto one state emerged from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea in which different groups are denied or afforded different rights based on ID cards, location etc.

Israel's occupation of the West Bank, which in 2017 will have lasted for half a century, has evolved into a complex system of control and exclusion, with Jewish settlers living among non-citizen Palestinians whose freedom to live in their own land is managed by a bureaucratic apartheid system of "permits" and physical obstacles and barriers.

Ironically, it was during the so-called Oslo peace process that elements of the apartheid comparison began to be even clearer.

In 1984, Desmond Tutu wrote that the so-called self-governing homelands - Bantustans - promoted by the apartheid regime were deprived of "territorial integrity or any hope of economic viability". They were, he wrote, merely "fragmented and discontinuous territories, located in unproductive and marginal parts of the country" with "no control" over natural resources or access to "territorial waters". This could have been written today about the Occupied Territories.

It is not simply the methods of Israeli repression that have parallels with the historic regime in South Africa - policies condemned last year by the United Nations Committee on the Elimwination of Racial Discrimination in terms of "segregation" and a breach of the prohibition of "apartheid". Israel in 2013 is echoing Pretoria's diplomats in days gone by when it comes to propaganda.

So, for example, just as in the 1970s and 1980s, today the Israeli ministry of foreign affairs claims that a boycott of settlement-produced goods hurts first and foremost Palestinian labourers. Even more revealingly, some Israeli politicians, jurists and advocates today sound the alarm about Palestinian birth-rates, equality, and the prospect of a democratic one-state solution in terms of "national suicide", the same discourse used by apologists for the apartheid South Africa government.

For South Africans, whose memory of apartheid is still raw, Israel is a target not only because it is a remaining example of a hated system, but because for the colonised indigenous population, today's apartheid is worse. As a South African newspaper editor, Mondli Makhanya, put it in after a 2008 trip to the Middle East: "It seems to me that the Israelis would like the Palestinians to disappear. There was never anything like that in our case. The whites did not want the blacks to disappear."

From veteran fighters and leaders such as Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu and Ronnie Kasrils, to human-rights campaigners working on initiatives such as BDS South Africa and Open Shuhada Street, a Palestinian rights campaign, there is a recognition that Palestinians are facing a struggle for dignity, equality - and life itself - similar to the one once waged, and won, in South Africa.

Ben White is a freelance journalist and author of Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner's Guide and Palestinians in Israel: Segregation, Discrimination and Democracy

benwhite.org.uk