Facebook has detected and halted more than 150 secret influence operations in the past four years that violated its policy against Co-ordinated Inauthentic Behaviour (CIB), the social media giant said.

Covert influence operations targeted public debates across both established and emerging social media platforms, blogs, major newspapers and magazines. They were orchestrated by governments, commercial entities, politicians and political groups, globally as well as locally, the California-based company found in a new report.

It defined influence operations as “co-ordinated efforts to manipulate or corrupt public debate for a strategic goal”.

“To keep advancing our own understanding and that of the defender community across our industry, governments and civil society, we believe it’s important to step back and take a strategic view on the threat of covert IO [influence operations],” the company said in a statement.

“While the defender community has made significant progress against IO, there’s much more to do. Known threat actors will continue to adapt their techniques and the new ones will emerge. Our hope is that this report will contribute to the ongoing work by the security community to protect public debate and deter covert IO,” it added.

Most of the CIB networks emerged from Russia (27), followed by Iran (23), the US (9) Myanmar (9) and Ukraine (8).

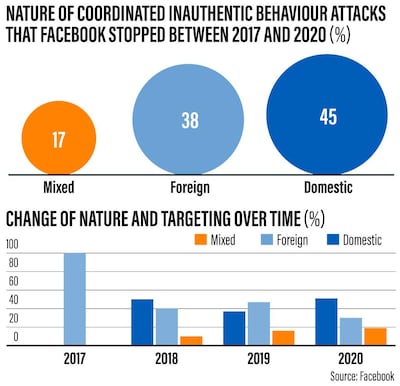

Of the more than 150 operations identified, 45 per cent were domestic in nature, 38 per cent focused solely on foreign countries and 17 per cent targeted audiences both at home and abroad.

Besides attempting to manipulate elections, influence operations targeted different events such as military conflicts and sporting events, the report said. State and non-state actors were involved, including military, intelligence and cabinet-level bodies, as well as cyber criminals, businesses and advocacy groups.

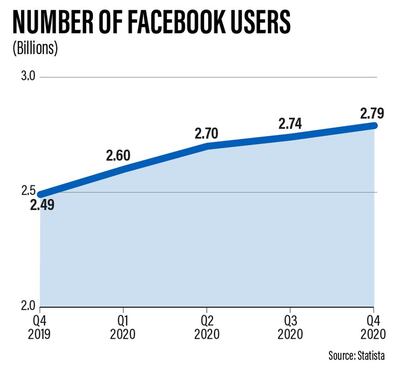

Facebook said influence operations actors will intensify their attacks in the coming months.

“Threat actors have not given up. As we collectively push IO actors away from easier venues of attack, we see them try harder to find other ways through.”

They will continue to “weaponise moments of uncertainty, elevate conflicting voices and drive division around the world, including around major crises like the Covid-19 pandemic, critical elections and civic protests”, it added.

In order to make these campaigns less effective, defenders have to “establish new norms and playbooks for responding to IO within a given medium and across society”.

“By shaping the terrain of IO conflict, we can become more resilient to manipulation and stay ahead of the attackers,” Facebook said.

Influence operations are rarely limited to one medium, so defenders should include traditional media, tech platforms, democratic governments, international organisations and civil society voices, it added.

Over the years, criminals have also changed their tactics to avoid the attention of authorities, the report revealed.

As Facebook attempted to make it harder for threat actors to operate high-volume, “wholesale” influence operations that target audiences at a large scale, they have shifted to narrower “retail” campaigns that use fewer assets and focus on small audiences, the report said.

Instead of running large, covert influence operations on social media, some actors have engaged in a phenomenon called “perception hacking" – giving the false perception that they are carrying out widespread manipulation, even when this is not the case.

For example, in the 2018 US mid-term elections, Facebook found an operation by a Russian agency that claimed they were running thousands of fake accounts with the capacity to sway election results across the US.

In response to increased efforts at stopping them, threat actors have also improved their operational security. They are getting better at avoiding language discrepancies and giving clues to the authorities, the report said.

There is also growing evidence of commercial actors offering influence operations as a service, both domestically and internationally. These can be used "by sophisticated actors to hide their involvement behind private firms, making attribution more challenging", it added.