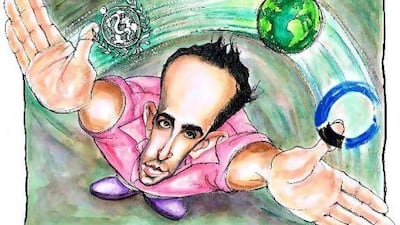

A Facebook addict partial to purple suede shoes and pink Polo shirts, Ghanem Nuseibeh looks like he has just come from a glitzy Manhattan cocktail party.

Yet he is the man investment bankers, business executives and even government officials turn to when they want to know what is happening in the Arab world. Not what appears to be happening on the surface, but what is really happening, and what it all means.

Biobox: Ghanem Nuseibeh Co-founder and director at Cornerstone Global Associates

Last Updated: May 27, 2011

Secret pleasure The bar at the back of the Emirates A380 on the London-Dubai flight "because you meet an amazing amount of people there. You are stuck there for seven and a half hours, and they're stuck with me chatting."

Worst fear Turbulence. "It's a problem because I travel at least once a month."

Favourite watch Omega Seamaster

Favourite sport (to watch) Cricket

Favourite sport (to play) "I run every day, but that's not really a sport. Swimming I'd say."

From his offices at Cornerstone Global Associates, the Jerusalem-born Londoner measures the impact of political and economic risk on companies and governments.

And never before has the 34-year-old's work been so in demand as now, as a wave of political protests grip parts of the Middle East and North Africa.

It has left few countries in the region unscathed and many investors are still on tenterhooks on what to do next.

That is why among the accessories to his colourful wardrobe are three mobile phones kept in a holster with another tucked away in his front pocket.

On this particular night, at his favourite haunt at Dubai's Icon lounge in the Radisson hotel, Mr Nuseibeh's phone rings with the caller's number withheld.

It is usually a sign that the caller is a powerful person who does not want his number known to others.

"You think, 'am I going to answer or not?'," Mr Nuseibeh says, although he eventually does, admitting he cannot ignore a call.

Among a select list of present and past clients published on the website of the political and economic risk consultancy he co-founded in 2008are the governments of South Africa and Singapore, the food and beverage conglomerate PepsiCo, the charity Oxfam and the UK's National Health Service.

Mr Nuseibeh is a self-confessed socialite and has built up an impressive list of contacts. He is also unconcerned about sharing his meetings with his friends on his Facebook page, although he names no names.

For all his openness, you would be forgiven for thinking Mr Nuseibeh is not all he is cracked up to be, but his colleagues at Cornerstone insist he is the real deal.

Dr Mark Somos, a Harvard-Cambridge academic and political scientist who is now interim managing director at Cornerstone, met Mr Nuseibeh at a London boarding school 18 years ago. He calls Mr Nuseibeh the "most trustworthy person I know".

"We kept in touch after school, and started working together four years ago. What I did not see at first, but gradually discovered, was the strength of his integrity.

"But I think it's his honour that makes him an excellent leader and a wonderful friend," Dr Somos says.

Another high-flying friend, Lucian Hudson, a former director of communications at the UK's foreign office and head of programming for the BBC's Worldwide channels, describes Mr Nuseibeh as a "young Kennedy - in the best sense of the word".

A team of about 45 people, which includes associates based around the world, work around the clock to resolve "crisis" situations at Cornerstone. Fees for the company's elistist clients can range from "the thousands, tens of thousands to the hundreds of thousands depending on the size of the project", says Mr Nuseibeh.

When he launched his company, however, nobody was anticipating an "Arab spring".

But the historic events of this year have seen the toppling of two governments and political upheaval in even normally placid Gulf nations such as Oman.

All stability has been pushed out of the equation and it has meant a drastic change in strategy for Mr Nuseibeh and his company.

"In the past year a lot of government and organisations had all sorts of medium to longer-term strategies that spanned three, five even 10 years," he says.

"That's completely on hold now, everywhere. The long term has sort of been frozen and now the medium term is the long term."

Mr Nuseibeh, trained precisely for these heightened times of political and economic risk, is in his element. "Things have been extremely unpredictable and people want very immediate answers that in some respect is not the core thing we'd like to do," he says.

"Everyone is now wondering, what is going to happen tomorrow? And they want to know now."

A New York investment bank last week voiced unease about the money it has locked up in Yemen, asking Mr Nuseibeh what the impact of political changes could be. Then he answered a call from a party of American students stuck in Cairo looking for an alternate location to continue their semester abroad.

Having become the go-to man for the governments and companies of the region, the wildly different time zones of the world mean there is little time for him to relax.

"Typically we've had calls, like 'what's happening in Qatar? Saudi? Kuwait?'," he says.

"It can be inconvenient and difficult because of things changing so rapidly."

Although the international media has covered developments in the region intensely, often from the frontline, Mr Nuseibeh says his political risk expertise goes beyond the average news story.

"You can't sit down and Google your way through political analysis," he says. "OK, there's a demonstration, but where we come in, is the 'so what'?"

Taking Saudi Arabia as an example, a worry for many companies as one of the largest economies in the Arab world, Mr Nuseibeh says he has had endless queries on whether the threat of any demonstrations would have an impact on business.

He says that in some respects he is doing a bit of journalism by trying to understand what everything means. But Mr Nuseibeh likens the research his organisation does to a barrister's chamber, rather than a hectic newsroom, with team members working diligently and intensely with clients on a one-to-one basis.

An intricate network of contacts including those "on the ground" ("not like spies or anything", he says, "but they know what's happening") in the relevant countries allow consultants to draw on many different resources. It means the standard of research limits employees to those with more experience.

"We don't employ graduates, not that there's anything wrong with them, but it's the way we structure our company," he says, pointing out that his staff are all seasoned professionals.

The secrecy of clients also has an important part to play in the organisation and Mr Nuseibeh's work, which is predominantly of a sensitive nature. It puts much emphasis on connections, and Mr Nuseibeh certainly has many of those. "I'm sure I've got answers for everything in that bunch of business cards," he says, laughing, of the thousands of people he has met over the years. His contacts include various politicians, business executives and economists, including those involved in Arab-Israeli politics, a matter of special interest for Mr Nuseibeh.

Confidantes from these circles include Prince Firas bin Raad of Jordan, who is a development adviser to the Middle East Quartet and Dr Karim Nashashibi, economic adviser to Salam Fayyad, the Palestinian prime minister.

It is not surprising he has accumulated so many contacts considering his resume.

He spent four years as a member of the Club of Rome, an influential think tank. He has also spent time working from the Gulf office of the Budapest-based think tank Political Capital Policy Research and Consulting Institute.

In what spare time he has, Mr Nuseibeh is also working on a doctorate concerning the urban environment via the University of Salford in England. It is a connection to the start of his career in engineering, when he worked for Atkins, a UK-based engineering consultancy.

He has been involved in the design of projects including the Azerbaijan-Turkey-Georgia gas and oil pipelines and the upgrade of the London Underground.

The pipelines propelled Mr Nuseibeh into the world of political risk.

"It was in that particular project that I got early exposure to balancing the needs, risks and opportunities of competing disciplines," he says.

"Basically the route of the pipeline that was chosen was the most difficult technically but the most favourable geopolitically."

Mr Nuseibeh has come a long way from his days in Jerusalem, where he grew up.

Flitting between there and London, he completed his schooling at Dulwich College, an independent boys' school in London, and then went on to study engineering at Imperial College London.

His father, Mohammed Nuseibeh, founded Al Quds University in Jerusalem and was its former chancellor, while his mother, Faida, runs a hotel business in the city. His three siblings are also doing well, one a banker at Deutsche Bank, another a civil engineer, and the third in the construction industry.

But Ghanem Nuseibeh is modest about his family's achievements: "We are a working, active family," he says.

Though he now divides his time mostly between Dubai and his riverside Chelsea pad in London, he has also clocked up impressive air miles in the past few months on his visits to clients.

A typical itinerary has seen him travel across four countries and two continents in the space of seven days.

This particular week, having just flown into Dubai from London, Mr Nuseibeh is planning a trip to Qatar and Jerusalem.

Having a tight group of contacts spanning various territories has more elusive benefits, considering the confidential nature of his work.

"What I've found extraordinary about the region is everyone is suspicious of everybody else," he says. "If you don't have the confidence and personal contact with that person you are dealing with, they will think you have been sent by someone to spy on them."

Mr Nuseibeh's image is an important part of his schmoozing success, particularly with clients as diverse as his.

"I try to be as open as I can with people so they know what I get up to - not that I get up to anything bad."

As he prepares for a flight to Qatar, Mr Nuseibeh is excited about meeting his latest client, although he is sworn to secrecy as to whom that might be.