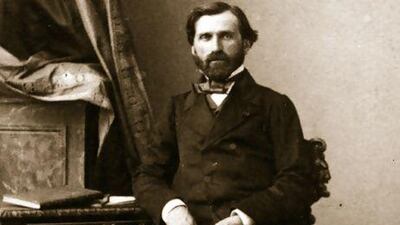

There's something strangely modern about La Traviata. While Giuseppe Verdi's 160-year-old opera is often staged in productions full of swinging crinolines, gilt mirrors and simulated candlelight, its storyline of lovers ruined by money and the need to keep up appearances still rings true today.

Now, this most popular of operas is getting an Abu Dhabi premiere (in concert form), at the Emirates Palace Auditorium on Friday to celebrate the bicentenary of Verdi's birth. Presented by the Italian Embassy, the opera concert will feature the singers Monica De Rosa McKay, Giacomo Patti and Giuseppe Deligia. The Larisa and Vitali Piano Duo will accompany and Professor Alessandra Priante, the cultural attache for the Gulf area, will narrate.

It's a chance to discover a piece that's not just stunning musically but also pushed forward new ideas about what opera could discuss.

Based on an earlier novel by Alexandre Dumas (he of The Three Musketeers), La Traviata follows the Parisian courtesan Violetta - young and beautiful but ill with tuberculosis. After some resistance, Violetta falls for the poor student Alberto and gives up her profession to live with him in the country.

They're happy for a while, but when Alberto's father begs Violetta to leave his son to save the family's reputation, it creates a rupture between the lovers that pushes Violetta reluctantly back to her old life, and on towards death.

This melodramatic structure, busy with glittering ball scenes, poignant bedside farewells and some of the catchiest music in opera, shows a familiarly Victorian sentimentality, a plot in which Violetta can be forgiven her wayward life essentially because she pays so dearly for it.

As the first opera Verdi wrote specifically to be performed in modern dress, La Traviata is nonetheless unusually forward-looking in its frankness. Portraying unmarried lovers in the present day was bold for its time - too bold, in fact, for Italian censors, who did not permit a modern-dress production until 30 years after its premiere.

There's also something unusually sympathetic in Verdi's depiction of Violetta, a sympathy that Flora Wilson, a fellow in music at King's College Cambridge, notes is absent in the original novel.

"Violetta is a pretty nasty character in Dumas's novel, sometimes verging on the repulsive," says Wilson. "The depiction of her in the play [which followed the novel] was much softer, partly no doubt because it had to pass via the censor. Verdi and [the librettist] Piave seem to have run with this change. Within the context of 19th-century ideas about gender, it's an extremely sympathetic opera - it's Violetta's opera and she really does get the best tunes."

So why this unusually generous depiction? Biographers have been quick to draw parallels between Violetta and the women Verdi loved in real life. Like Violetta, Verdi's first wife, Margherita, died in her 20s, while Verdi's second life partner, the soprano Giuseppina Strepponi, did not marry the composer for around a decade after their relationship began. While many have read the sickly, unmarried Violetta as a synthesis of these two women, it's also the case that the opera-going public of Verdi's time drew only a vague line between courtesans and singers.

"What's arguably more interesting is that opera singers were seen to be associated with courtesans in the popular imagination," says Wilson. "There was a sense that for a woman to put herself on the stage was to declare herself available, which of course wasn't the case. The popular link with [Verdi's partner] Strepponi is a product of the same conflation."

To Verdi's great credit as a composer, Violetta's character development comes not just through words but also through the music she sings, which begins with fizzy, show-stopping arias and progresses to something deeper.

"Verdi really writes her psychological development into the music," says Wilson.

"In the first act, she's a party girl, and her vocal lines are very florid and heavily decorated. By the final scene, however, she's dying and has become vocally fragile, so there's even a moment when she stops singing altogether and the orchestra takes up her melody instead."

Just as Verdi's music slowly strips away its embellishments, so La Traviata's plot moves away from the shallowness of high society to situations that show its glittering inhabitants' underlying dignity. In a world that still overvalues appearances, it's no wonder that this ageing opera doesn't really feel that old at all.

La Traviata is at 8pm on Friday in the Emirates Palace Auditorium. Tickets are available at www.timeoutickets.com

Opera's fallen women

The operatic repertoire is full of women who break rules and end up badly. Joining La Traviata's Violetta, Bizet's gypsy cigar-maker Carmen also steps outside society's rules, in her case joining a group of bandits and taking a lover, only to be killed when she tries to leave him.

Alban Berg's modernist masterpiece Lulu likewise follows a beautiful woman whose looks stir violence in the men around her, ending with her murder in London by Jack the Ripper. Even the fragile, harmless Mimi of Puccini's La Bohème dies soon after leaving her lover Rodolfo to take up with a wealthy viscount.

The fate these women suffer is often presented as tragic - Violetta in particular has become a noble figure by her death - but it is striking that so many librettists felt that operas showing a woman rejecting convention could only end tidily with her death.

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.