“There was a time when the cleaners refused to clean the cases in the mummy gallery,” said Jim Peters, collections manager in the department of prehistory and Europe, thinking back to the early 2000s when he first started working at the British Museum. “They genuinely believed that the mummies were moving.”

The Upper Egyptian or the mummy galleries are full of amulets and sculpture, daggers, ancient cradles and hieroglyphs, but I could never focus on them. I don’t know how to study a piece of pottery with a dead person lying exposed nearby. It seems a weird thing to ask of anyone, especially the droves of children who are brought to the museum.

What to make of the cleaners’ refusal to enter the Egyptian galleries? The staff seemed to stage a strike on the basis that they had agreed to clean the vitrines, but being complicit in the bald transgression of exhibiting the dead became too much once the dead began to stir.

Imagine playing dead for centuries, tourists feeding on the sight of your bare bones day in and day out and, even when it was quiet, the cleaners and security guards still keeping an eye on you.

Among the guards, there was a silent consensus that things often go awry in the Upper Egyptian gallery, where the warders are every day besieged by the occasionally unruly dead.

'Something followed me home'

On a busy afternoon in the gallery, I spoke to an older member of Visitor Services. She said that one day the exhibitions team was swapping out the so-called Gebelein Man from a glass display case in Room 64 and that she absent-mindedly sat on a coffin crate as they were moving the body. One of her colleagues was quick to warn her, “He may not appreciate it. Careful.”

In the middle of the night, she felt someone tugging at her duvet at the foot of the bed. As she came to consciousness, she saw a shadowy figure flee the room. She felt as if she were back in Room 64 at the moment when she sat on that coffin, and knew: “Something followed me home.”

At the far end of Room 65, a 2nd-century sandstone relief from the funerary chapel of Kushite Queen Shanakdakhete takes up almost the entire wall. An anonymous warder told me that, some years ago, a little boy was sitting on one of the benches in front of the relief. His parents took two photographs seconds apart. In the first, “There was, what you could only describe as a black mass” rising out of the floor, “right next to where their son was”, threatening to overtake the child. “When they took another photo, it had gone.”

Phil Heary, 29-year veteran of Visitor Services, never once came across a ghost until he worked at the museum, where he had several revelatory experiences, all in the Upper Egyptian galleries.

“The mummies. The mummies. In 61 and 62,’’ he intoned. In Room 61, we find the deconstructed tomb chapel of Nebamun, a scribe from Thebes of the 13th century BC. Room 62 is an emporium of sarcophagi, wrapped bodies and grave goods. A mummified cat stands on the second tier of a glass shelf, watching as you pass through the doorway.

Tempest of restlessness

Phil remembered: “One of my first experiences was when I went up to the Egyptian mummy gallery in the middle of the night, to see if things were all right. It was unbelievable. This was a summer’s evening and you can see the breath coming out of my mouth. It was like walking into a freezer. And it had this sort of smell. My stomach turned over. The feel about the gallery was you want to get out. It was scary.”

In the tempest of restlessness let loose in the gallery, Phil wrestled with distinguishing popular myths of Ancient Egypt from his own pre-existing beliefs and lived reality. He arrived at the need to respect the sanctity of the dead.

“A lot of mummies should be back in their graves. They shouldn’t be in the museum,” Phil spoke firmly, with a candour found only in former employees.

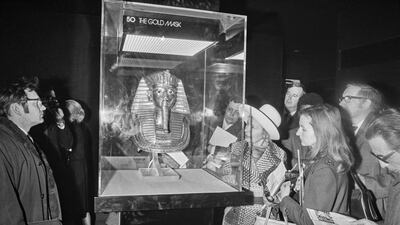

“That’s why Tutankhamun’s back in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings. They’re all back in the tombs, because they realise now that you’re mixing the spirits up. I think there’s restless souls up there.”

The British Museum through the years – in pictures

At what point does a person become unworthy of a dignified rest in death? If I told you, dear reader, that I have a single human corpse stashed away in my basement, you’d probably think I was a psychopath, and rightfully so. If I told you that I have a dozen skeletons I dug up myself to wow guests, there’s a strong chance I’d be writing this from jail.

We are all too well acquainted with the fact that crimes of magnitude are more likely to evade corrective measures. Still, it beggars belief that the British Museum holds over 6,000 “sets” of human remains.

All mixed up

People from former British colonies and protectorates, and lands once subject to British occupation, administration and meddling, are over-represented in the obscene, incomplete spreadsheet of body parts - the dead from India, Ireland, Iraq, Iran, Oman, Jordan, Nigeria, Uganda, Ethiopia, Borneo, Vanuatu, New Zealand, Australia, Papua New Guinea, North America and China join scores of Egyptian remains mixed up with people from Germany, France, Latvia, Norway, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Greece.

Whatever the British Museum can tell us about the burial practices of other cultures, the more striking is the curious cultural practice of denying burial to others, and exhibiting or stowing them away. The collection evidences a culture of gathering the dead as loot, of treating the dead as objects of study.

Are the dead really held captive for research purposes, or out of ignorance? Are they restricted from going home as a matter of imperial pride, or a paralysing sense of shame? Are they stranded as a result of apathy, or an active and sustained refusal to acknowledge the humanity of others? I ask well aware that these binaries do not hold; the museum is all mixed up.

An examination of the Upper Egyptian gallery’s spectral disquiet leads us inescapably not into the underworld as traversed by Ancient Egyptian gods and dead, but into the basement, the multi-storey netherworld underlying the British Museum.

British Museum artefacts – in pictures

At the building’s foundation is a congregation of unearthed dead, pulled from across the planet, which millions of visitors a year unknowingly stomp and stroll all over. With 99 per cent of the museum’s holdings hidden underfoot, what we experience as the floor is the ceiling for the overwhelming majority of its inhabitants.

The exhibition spaces serve as the fleeting exception, window-dressing for the museum’s core function - Storage, the domain of the disappeared.

This is an edited extract of 'Ghosts of the British Museum: A True Story of Colonial Loot and Restless Objects', by Noah Angell (Monoray, £20), which is available in hardback now.

(The National contacted The British Museum to extend a right of reply to the criticisms contained in the above extract. The offer was declined. Anyone wanting to know more about the institution's Human Remains policy can visit its website.)