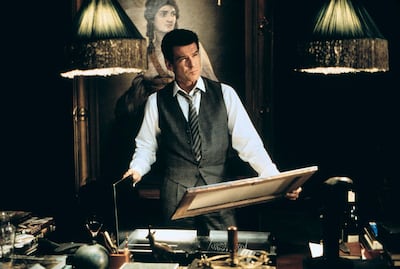

Art theft in the movies is generally characterised by a convoluted, high-tension plot, like The Thomas Crown Affair, which depicted an audacious daylight robbery carried out by hundreds of swift-walking men in bowler hats.

In real life, as the British Museum has recently discovered to its cost, both financially and reputationally, art theft is far more prosaic and almost certainly an inside job.

An enquiry has been set up into a serial thief found to have been operating at the museum for two decades, during which more than 1,500 items have reportedly been taken. Roman jewellery, glass and gemstones thought to be worth tens of millions of pounds have disappeared.

Some have turned up on eBay, others are reported “missing, stolen or damaged”. A curator, Peter Higgs, has been sacked. He denies any wrongdoing, but the Metropolitan Police have opened an investigation and interviewed a person.

According to an internal investigation conducted by the museum and reportedly seen by The Daily Telegraph, Mr Higgs, the museum’s curator of Greek collections, Greek sculpture and the Hellenistic period, was last week named as the prime suspect behind the disappearance of numerous artefacts held in the museum’s collection, many of which he is alleged to have sold on eBay, often for a tiny fraction of their estimated value. One Roman object, dating back more than two millennia and valued at up to £50,000 ($62,963), was allegedly sold for £40 on the site.

George Osborne, beleaguered chair of the British Museum, is well used to the fierce heat of a public scandal. As a former chancellor, co-architect along with former prime minister David Cameron of the age of austerity, he rode out many controversies. Mr Osborne, who took office last year, appears to have acted faster than the British Museum management but his intervention looks to have come far too late to staunch deep institutional damage.

After all, the museum had been warned that its artefacts were turning up for sale on the auction site but brushed aside the tip-off. An art dealer alerted the British Museum to items allegedly stolen from the institution in 2021 but was told "all objects were accounted for".

Ittai Gradel alleged in February 2021 he had seen items online belonging to the museum, according to correspondence seen by BBC News between Dr Gradel and the museum. Deputy director Jonathan Williams responded in July 2021 to Dr Gradel, saying "there was no suggestion of any wrongdoing". Mr Higgs, whom Mr Gradel had named as vendor, was even later promoted.

“Concerns were only raised about a small number of items, and our investigation concluded that those items were all accounted for," said outgoing director Hartwig Fischer this week.

“We now have reason to believe that the individual who raised concerns had many more items in his possession, and it’s frustrating that that was not revealed to us as it would have aided our investigations."

Mr Fischer stepped down with immediate effect on Friday as the crisis deepened. In a statement he said the comments he had made about Dr Gradel were "misjudged" and he extended his regret for his choice of language.

Dan Hicks, professor of contemporary archaeology at the University of Oxford, said the issue of how the museum acts as custodian of its treasure had not been fundamentally addressed by Mr Fischer and his team.

“It will shock many people to learn what everyone in the museum sector knows, that the databases are not complete.” He says the recent incident may not have been possible if the museum had properly invested in cataloguing, and that the oversight is an example of “arrogance and exceptionalism”.

“How can you care for something if you don’t know what you have?” Prof Hicks said, adding: “This wouldn’t be possible if you had a comprehensive database of everything in the museum”.

He called for all bigger museums to publish formal documents in the same way that smaller museums must. “Why is it that these incredibly rich organisations have so much worse a collection’s oversight than smaller university museums or city museums?”

The British Museum says the majority of its items are registered, and that five million of its eight million artefacts are available to look at on a public database. However, less than 1 per cent of its collection is on public display and therefore less carefully monitored.

The museum has experienced thefts before, even from the public galleries. In 2002 it launched a security review after a 2,500-year-old Greek statue was stolen by a member of the public. The thief took the 12cm marble head and left with it undetected. At the time the museum said no permanent guard had been on duty in the Greek Archaic Gallery despite it being open to the public.

Alice Farren-Bradley manages the global Museum Security Network, which shares information on security, common threats and risks with its 1,500 members. She says artefacts that are the most fragile and unlikely to go on display or on loan are kept in “deep storage”. Some are in general storage and others are in study collections, accessible upon request by academics. Ideally, every item should be inventoried with a detailed description, number and photographs from several angles, she says, but due to their age and size, most collections do not have 100 per cent of items catalogued.

The British Museum has left itself open to international scrutiny. Speaking to The Economist, Christos Tsirogiannis, a Unesco-affiliated antiquities trafficking expert, says the British Museum theft is “probably the worst case so far … no one expects that to happen in a museum”.

Artefact thefts do happen “every single day around the world”, according to Christopher Marinello, lawyer and founder of Art Recovery International, an organisation that specialises in locating and recovering stolen works of art worldwide, and the Art Loss Register, which describes itself as the world's largest private database of lost, stolen and looted art, antiques and collectibles. The register currently lists about 700,000 such items. Mr Marinello says it is shocking when large institutions, such as the British Museum, are caught off guard.

Before this story emerged, the British Museum had been at the centre of a series of restitution debates over contested artefacts, most notably the Parthenon Marbles, the Benin Bronzes and the Ethiopian Tabots. Its leadership has defended its collection against such restitution claims by arguing that the museum is capable of conserving and protecting artefacts uniquely well. In the wake of the scandal, the Greek government has, not unnaturally, spoken about the return of the Parthenon Marbles, The security questions raised by the missing objects “reinforces the permanent and just demand of our country for the definitive return” of the Marbles, said Greece’s Minister of Culture, Lina Mendoni.

“The loss, theft, deterioration of objects from a museum’s collections is an extremely serious and particularly sad event … in fact, when this happens from within, beyond any moral and criminal responsibility, a major question arises regarding the credibility of the museum organisation itself. The Ministry of Culture is following the development of the issue with great attention.”

Nigeria too is now petitioning for the return of the Benin Bronzes.

Until the results of the police investigation, and the museum’s own enquiry, the thefts would seem to be the result of a toxic mix of complacency – those airy denials after wrongdoing was alleged in 2021 – careless safeguarding and personal greed.

Dr Frank Furedi, an academic and author, also argues that decolonisation – hunting out every connection of museum items to perceived past injustices – has distracted museums from looking after the irreplaceable objects in their trust, leading to “cavalier ineptitude”.

For its part, the UK Museums Association said that a lack of investment in the sector in the age of austerity inaugurated by Mr Osborne in high office led to the collapse of safeguarding procedures.