HAVANA // They speak little Arabic, they do not have an imam or a purpose-built mosque, but Cuba’s small Muslim community practice the faith and will quietly mark the end of Ramadan as best they can.

In Havana’s old quarter, a green and white minaret sits on top of an old colonial-style building. It is here where Cuban Muslims have gathered for the past year to pray.

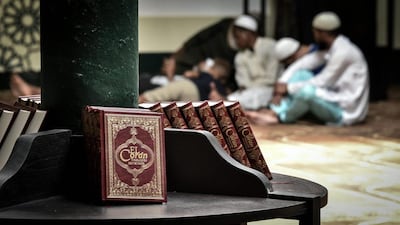

Inside, the walls of the prayer hall are decorated with Arabic calligraphy and a Palestinian flag. The copies of the Quran have been translated into Spanish.

“Salam allaikum,” says a smiling man named Javier as he welcomes visitors in Arabic on a hot summer afternoon.

He was born into a Catholic family but converted to Islam two years ago.

“The text of the Bible seemed incomplete to me, so I changed religion,” Javier said about his decision, an unusual one in a country where 70 per cent of the population observes a blend of Christianity and traditional Afro-Cuban beliefs.

There are thought to be as many as 10,000 Muslims in Cuba, making up less than 0.1 per cent of the population. Most are converts.

Islam came to Cuba mainly via the 900 or so students of Pakistani origin who began arriving during the 1970s to study at Cuban schools and universities. The embassies of Middle Eastern countries also helped to spread the word. In 2001, Sheikh Muhammad Nassir Al Aboudy, assistant secretary-general of the Muslim World League travelled to Cuba to seek permission to establish an Islamic organisation to support the island’s Muslim community.

“Tourists often come through this street and they are so surprised when they realise they are looking at a mosque,” said Ahmed Aguelo, who converted to Islam 17 years ago and runs the prayer hall where some 200 worshippers gather for Friday prayers.

“I am not officially an imam, as there is no training course here,” he said. “But I know the basics.”

Cuba’s Muslims have been clamouring for their own house of worship for 25 years and a few hundred metres away, a sign advertises the construction of a purpose-built mosque on a two-hectare piece of land. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan promised it to Cuba in February 2015, but building has yet to begin. In June 2015, the Cuban government gave the go-ahead for the inauguration of the prayer hall in the heart of Old Havana as “Cuba’s first mosque.”

“We write ‘mosque’ at the entrance because it works like one,” said Rigoberto Menendez, director of Arab House, which is behind the mosque project. “A real mosque would have more space but the main thing is for Muslims to be able to come together in one place”.

In the absence of an official place of worship, Cuba’s Muslims have had to improvise. “We would meet in apartments around the city,” said Pedro Lazo Torres, who converted in 1988 and is considered Cuba’s first Muslim.

Though he says he is able to practice his religion “totally freely” Cuban Muslims face other, more practical problems, especially during the holy month of Ramadan. For example, breaking the obligatory fast in the traditional way, by eating dates is difficult in Cuba, where there are no dates.

“Everything is imported. The Saudi embassy supplies us with dates, traditional garments, halal meat. With the help of God, we get by,” said Mr Torres, who goes by the name Yahya.

Alen Garcia, a 33-year-old of African descent, said he gave up a lot when he converted to Islam.

“I lost friends when I told them I wanted to become a Muslim. To convert was to renounce drinking rum, eating ham, going to parties and dancing salsa,” he said. “In other words, it meant renouncing much of Cuban culture.”

There are no Arabic courses at Cuban universities but Arabic-speaking students from Chad, Afghanistan and Libya who attend the Latin American School of Medicine there give free classes in the language of the Quran. Cuban Muslims also study Arabic with apps they can use offline.

As the time approaches to break the day’s fast, the prayer hall fills. Children play on the side of the room reserved for their mothers.

The man who distributes food is named Leonel Diaz, but he goes by Mohammed. He converted at age 73.

“It is never too late to welcome a good thing,” he said.

He agrees to discuss Guantanamo, the US prison for terror suspects that opened at a US-held base in eastern Cuba after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

“States must find a solution to close this prison,” he said.

He noted that Colombia is close to reaching a peace accord with Farc leftist rebels after a half century of war.

“I would like the same agreement for the Muslims who are held in Guantanamo,” said Mr Diaz.

Yaquelin Diaz, who now uses the name Aisha, lived in Spain for eight years and it was there that she converted, thanks to a Pakistani brother-in-law.

“Because of our habits lots of people think we are foreigners. They cannot imagine that there are Muslims in their country. But Islam is expanding in Cuba.”

After the revolution of 1959, Cuba became an officially atheist state and all religious practice was severely limited. But over time the restrictions eased and after a constitutional reform in 1992, Cuba became a secular state.

Aisha said the only thing missing in Cuba is a shop that sells religious garments.

“Our brothers from Saudi Arabia give them to us, but we cannot keep living off their charity. We need our own stores, in our own style. We must be able to promote Islam in Cuba.”

Cuba’s Muslim minority hs already reduced at least one spiriting star. Juan Carlos Gomes, ten times World Boxing Council cruiserweight champion converted to Islam ten years ago.

* Agence France-Presse