On February 3, US General Mark Milley — the highest-ranking officer in the US military — issued a warning that Ukraine would be over-run in 72 hours in the event of a Russian invasion.

The US had strong intelligence on Russia’s intentions, but some of Gen Milley’s prediction was informed by Pentagon-sponsored war games, many of which he had been involved in during the run-up to war.

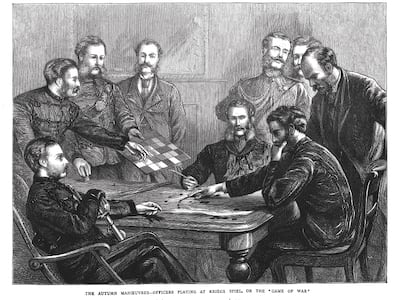

Some of these 'games' are expensive computer simulations. However, others are literally games, played with dice, playing boards and counters, sometimes augmented by computers and expert adjudicators, to identify weaknesses in future conflicts and train officers.

In the past 200 years, some of these war games have helped change the fate of nations, from the fall of France in the Second World War to the 1991 Gulf War and quite possibly, the ongoing war in Ukraine.

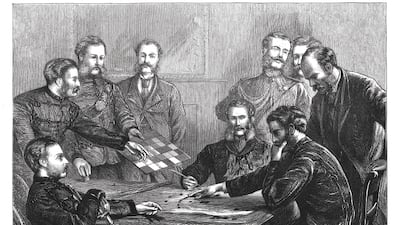

The origins of war games

The practice goes back to the early 19th century and the work of a Prussian officer, Lieutenant Georg von Reiswitz, who convinced his seniors that war could be re-created on a map, using red and blue counters for opposing forces, rules and dice.

“War games are well-understood models that integrate terrain, forces, weapons, space and time, and they are invaluable to turn knowledge into understanding,” says John Curry, a senior lecturer at Bath University, specialising in games development, who has worked with the UK Ministry of Defence and the Pentagon on war-gaming.

“Operational analysis gives us clear guidelines on rates of advance, daily casualties, the effectiveness of armour in towns,” he says, referring to analysis that models these aspects of war using historical and contemporary data.

That data can then become the basis of a game.

Cheaper than holding full-scale military exercises, war-gaming soon became commonplace by the turn of the 20th century in officer-training schools across Europe, the US and Japan, where the practice was introduced by German advisers.

War games have sometimes been spookily accurate in predicting outcomes but for many, their main role is not prediction, but training.

“There is a strong interest from the military to use war-gaming as part of their curriculum due to both cost and flexibility,” says David Freer, chief executive of commercial war-gaming company, Wargame Design Studio.

Mr Freer’s company produces games designed by the late John Tiller, who worked on 20 gaming and simulation projects for the US Air Force and Navy.

“The ability to use it as a learning tool, as well as putting students into interactive roles that can be networked and repeated, are all positives,” Mr Freer says.

Mr Freer’s work is at the point where the military use of war-gaming and the civilian hobby side of the pursuit overlap.

This overlap came to light with striking speed in 1990, when Saddam Hussein’s army invaded Kuwait.

On August 2, 1990, former Pentagon employee Mark Herman was pulled away from his day job —designing war games — to help planners understand the crisis.

Herman had designed a detailed game called Gulf Strike, which provided a rough, but ready-made recreation of US, Saudi Arabian and Iraqi forces in the Middle East.

Defence department staff hurriedly modified the game using classified information and through August, used Gulf Strike to plan the war.

By August 3, initial games suggested that Saddam Hussein had next to no options for victory, although a powerful computer simulation, TACWAR, would assist with the finer details of planning.

Predicting the future

The Prussian mastery of the games would carry over to the German army of the interwar years and later, Hitler’s military.

The Nazis used it to terrifying effect planning the invasion of France, holding multiple “map exercises” using counters before the invasion.

But like any activity that can influence the course of a war, the information war games produces might not be listened to by policymakers.

The Nazis’ experience with war-gaming illustrated the latter issue when they invaded Russia in 1941.

German war games highlighted a major flaw in the Nazis’ logistical capability: getting supplies for a four million-strong invasion force deep within Russia.

Eager to keep Hitler happy, senior German commanders simply ignored the game results, with disastrous consequences.

Twenty-three years later, the US conducted a war game with dozens of participants working through the Vietnam crisis.

That game, Sigma II-64, predicted that heavy US bombing of Communists in Vietnam would not guarantee victory.

The game showed that a large US ground force would be needed, which could spark American public opposition to the war — eventualities that came to pass.

Peter Perla, a war-game designer at the Centre for Naval Analysis and author of The Art of Wargaming: A guide for professionals and hobbyists stresses the problem here is the “openness of decision-makers to taking aboard the insights provided by the games, not merely their overall results, and using them to inform, rather than dictate, their subsequent decisions.”

This process has worked spectacularly in the past: in around 300 war games before the Second World War, the US Naval War College helped inform the future size, capabilities and strategies needed in a major war.

US Admiral Chester Nimitz would later say the games were essential for planning victory against Japan.

“Because war games often look at future possibilities, they can sometimes prove prescient,” Mr Perla says.

“The problem, of course, is that what gets reported are those occasions when a game got something right. Less reported are those occasions when they got it wrong. What tends to be forgotten, for example, is that a lot of the Naval War College interwar games ‘predicted’ things that did not occur in the war,” he says.

Milan Vego, a professor at the US Naval War College, also cautions that games should not be seen as a crystal ball.

“The Germans used the games to familiarise the players with a future theatre of conflict. But more important for them was to have a number of scenarios and the idea was that the more scenarios you play, some of them will resemble a real situation,” he says.

“You cannot predict, nobody knows what will happen.”

Mr Perla says that the games are useful guides to what might happen in real conflict.

“My simple bottom line is that war games do not predict, but war-gamers do. By which I mean that a war game can contribute to the predictive capability of those who participate and study the problem it addresses,” he says.

War-gaming Ukraine

The idea that war games are not for prediction may go some way to explaining why US-sponsored war games have frequently shown former Soviet states suffering swift defeat against Vladimir Putin's Russia, as Gen Milley feared.

Before the war, several games, some classified, others reported in the media, saw Ukraine and Baltic states quickly overrun by Russian forces, even with Nato units in place.

Sebastian Bae, a colleague of Mr Perla, has argued that winning these games is not the point, stressing the importance of playing to understand future conflict dynamics.

For Mr Curry, the games that featured overbearing Russian might are still a problem, and game designers should go back to the drawing board.

“Analysts prior to the war were describing the war in narrative terms [a story] rather than using war games based on known military history. Anyone, including me, who designed a war game prior to the war would have said that the idea of the war being over in 15 days was ridiculous, unless Ukraine suffered a national failure of morale and the state collapsed,” he says.

“The Russian logistics were insufficient to support an opposed advance (ie the Russians have to manoeuvre and shoot at active opposition). Anyone designing a war game would realise these realities before they ever started putting counters on the map,” he says.