Since the first World's Fair, the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, countries have sought to stand out from the crowd with their pavilions.

The structures — which are usually taken down at the end of an Expo — have over the years thrilled tens of millions of people with their unconventional architecture and futuristic exhibits.

Here, we look back on a few of the most notable showings in history.

Paris 1889: 'monstrosity' to national monument

Today, Expo organisers are keen to secure a ‘legacy’ from events, usually in the form of urban regeneration or through a long-term boost to tourism.

But none can hope to prove as successful as France in 1899, an event responsible for one of the world’s most recognisable monuments and the creation of a national icon.

The Eiffel Tower served as the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair, then the tallest man-made structure in the world, and was famously criticised by some of Paris’s top architects and intellectuals.

After the planned design was revealed, leading figures branded it “useless and monstrous” and launched a campaign to have construction cancelled.

The “hateful column of bolted sheet metal”, they warned, would mean “all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream”.

Even after it was built, some were not convinced. One critic, the author Guy de Maupassant, supposedly ate lunch in the tower's restaurant every day because it was the one place in Paris where the tower was not visible.

But it is now the most visited paid-for tourist attraction in the world, synonymous with Parisian romance, style and culture.

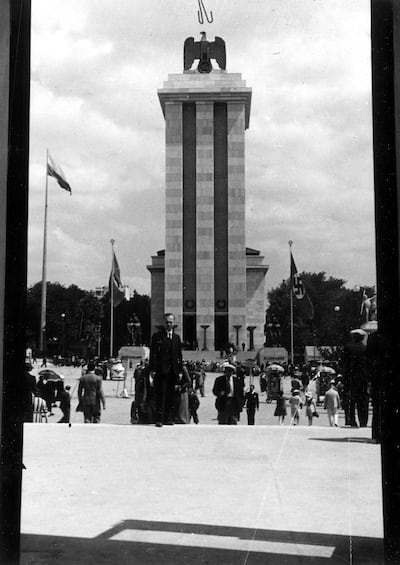

Paris, 1937: Hitler overshadows the Brits

As Europe teetered on the brink of a second devastating conflict in as many decades, the World Expo took place once again in Paris, France.

Then still a huge global power, it might have been expected that the UK would come up with a creative way of showing off its might.

Instead, its showing was “really pathetic”, according to Nick Cull, professor of public diplomacy at the University of Southern California and an expert on world expositions.

The centrepiece of the exhibit, he said, was a giant photograph of then-Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain fishing in a river.

In contrast, Nazi Germany created a huge monument, designed by Adolf Hitler’s architect Albert Speer, that was so impressive that even the French judges awarded it a prize.

It stood opposite an equally imposing Soviet structure, topped with a statue of a male worker and a female peasant, their hands together, thrusting a hammer and a sickle.

However, Britain learnt its lesson in time for the New York Expo just two years later. A surprise visit from the King George and Queen Elizabeth — described as the UK’s “secret weapon” by Professor Cull — ensured its next showing was seen as far more successful.

Brussels, 1958: the world's last 'human zoo'

Held in Belgium, the host country was keen to present itself as a global player at what was billed as a major postwar celebration of modernity.

But one aspect of the Belgian pavilion has not aged well.

A Congolese ‘human zoo’, where visitors were invited to gawp at black families in a mock African village, now appears spectacularly ill-judged.

The participants carried out ‘traditional’ activities such as craft-making behind bamboo fences, in an attempt to show how the Belgian colonialists had ‘civilised’ the country.

They were also subjected to racism from onlookers, who “threw money or bananas over the closure of bamboo” to elicit a reaction, a journalist reported at the time.

The Congolese complained of cramped accommodation, boredom and daily abuse at the fair.

Many refused to carry on and went back home, and the “exhibit” closed down early.

The Kongorama, as it was billed, and other exhibits like it which were once popular in Belgium, are now seen as a source of shame in a country still grappling with its colonial past.

It went down in history as the world’s last human zoo.

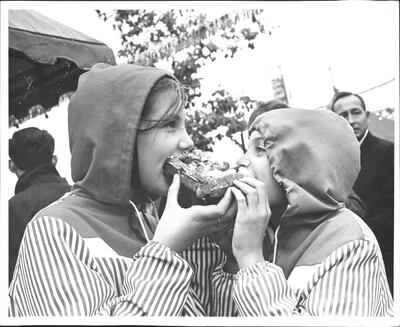

New York, 1964: Sangria and waffle batter make their mark

The 1964 World’s Fair in New York was controversial at the time, with organisers coming into conflict with the Bureau of International Expositions, the event's governing body.

Officials refused to officially sanction it and as the row deepened they took the unusual step of calling on its members not to take part.

The event went ahead anyway and its impact, at least in terms of US food and drink preferences, is still felt strongly today.

When nearby restaurants sought to take advantage of fairgoers by hiking their prices, tourists turned to the pavilions themselves for exotic refreshments.

The Spanish pavilion was serving a drink few Americans had ever heard of — Sangria. Popularity of the punch boomed and it has proved a staple of outdoor gatherings in the US ever since.

The fair also gave Americans their first taste of Belgian waffles — thicker and lighter than those they were used to. Demand was so high that Maurice Vermersch and his family, who had travelled to the US to serve the treats, had to hire 10 workers just to cut strawberries for toppings.

The variety has been ‘king of the waffles’ in the US ever since. MariePaule Vermersch, who helped her parents serve the waffles in 1964, moved from Europe to New Mexico but returned to New York in 2014 to help celebrate the 50th anniversary of the fair.

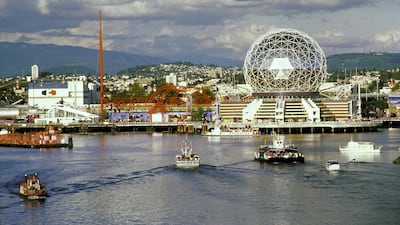

Canada, 1967: a dome fit for a King

The 1967 World Expo had originally been due to take place in Moscow but the Soviet Union cancelled its plans, fearing the security implications of opening up to millions of visitors and exposing locals to an uncensored version of the West.

Canada stepped in, and went on to stage one of the most successful Expos of the 20th Century.

And as if to rub salt into the wound, the US - the Soviets' arch rivals - created one of the most memorable pavilions ever in Montreal.

In a geodesic dome designed by Buckminster Fuller, the American pavilion exhibited US advances in the space race and cultural arts.

A replica of the Moon's surface, reconstructed by photographs, was on display alongside props from hit movies, including Ben-Hur, and one of Elvis Presley's guitars.

The USSR’s display was also a success, with a stunning glass and steel structure and most notably its curved roof, now seen as one of the finest examples of Soviet Modernism.

It was eventually taken back behind the Iron Curtain and, after lying in storage for a decade, was put back up in Moscow.

But it was Fuller’s dome for which the Canadian Expo is best remembered — and it is still in use to this day as a museum dedicated to the environment.

Osaka, 1970: Japan stakes claim to the future

The first ever Expo held in Asia, the Osaka event is now seen as being crucial in remaking the image of Japan - which at the time was still strongly associated with its actions during World War II.

The event became known for its stunning experimental architecture and, rather than looking to the past, Japan focused on showing off hi-tech innovations for which it is known today.

The first ever IMAX film was shown at the Expo, which also featured demonstrations of early mobile phone and high-speed ‘bullet’ train technology.

Another popular attraction was a piece of moon rock — which had been brought back to Earth by US Apollo 12 astronauts the previous year.

Japan would go on to hold three more Expos elsewhere in the country, in 1975, 1985 and 2005. The event will return to Osaka in 2025, 55 years after its inaugural show.

China, 2010: a new superpower rises

Coming two years after the Beijing Olympics, the Shanghai Expo was seen as part of cementing China’s status as a 21st Century superpower.

Its imposing pavilion, known as the Oriental Crown, was the largest and most expensive in Expo history, costing an estimated $220m (Dh808m). It towered over all other countries’ offerings.

The intricate design was intended to show off elements of the country’s history, inspired by the dougong roof bracket, which had been in use for 2,000 years, and a traditional cauldron.

Once inside, visitors were given a crash course in Chinese history, philosophy, its rapid economic development over recent decades and its vision for the future.

A rooftop garden was designed to incorporate traditional Chinese landscape, with several sustainable elements also incorporated into the building design.

The pavilion was seen as a highlight of the most well-attended Expo ever, with 73 million visitors. It has since become the China Art Museum, one of the largest museums in Asia.