As rioting, petrol bombing and fighting against police once more blight the streets of Northern Ireland, it is worth recalling two anniversaries. One is the Good Friday Agreement. It took years to negotiate but it brought peace to the island of Ireland when it was signed on Easter 23 years ago this month, on April 10, 1998.

The other anniversary is of an event 100 years ago, when Northern Ireland came into existence. That existence has baffled some English politicians ever since.

In May 1921, the United Kingdom split apart. After an uprising and the most horrendous bloodshed, 26 of Ireland’s 32 counties broke away from the UK to become what is now the Republic of Ireland. The other six counties, including Fermanagh and Tyrone, remained in the UK as Northern Ireland.

These momentous events came as Europe was exhausted by the effects of the First World War. In the House of Commons in 1922 Winston Churchill famously acknowledged that the historic bitterness between Protestants (who wished to remain in the Union with the UK) and Catholics (mostly Irish Nationalists) had not changed despite the profound changes everywhere else: “Every institution, almost, in the world was strained. Great empires have been overturned. The whole map of Europe has been changed ... but as the deluge subsides and the waters fall short we see the dreary steeples of Fermanagh and Tyrone emerging once again. The integrity of their quarrel is one of the few institutions that has been unaltered in the cataclysm which has swept the world. That says a lot for the persistency with which Irish men on the one side or the other are able to pursue their controversies.”

British prime minister, Boris Johnson, wrote a book about Winston Churchill, yet he has now blundered badly on Northern Ireland, provoking the anger that has led to violence on the streets. Mr Johnson was repeatedly warned that the Brexit deal he negotiated with the EU could endanger peace and reignite "the integrity of the quarrel" in Ireland. It has. Mr Johnson has failed to understand that Northern Ireland’s border with the Irish Republic, from which it so painfully separated a century ago, was an issue over which men and women on both sides were prepared to fight, to kill and to die for.

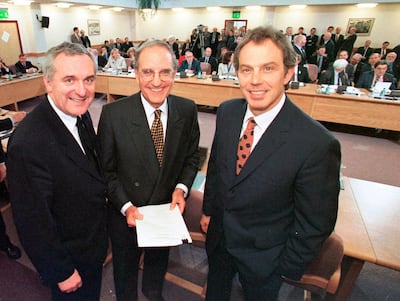

Desperate to secure a Brexit deal and to boast that he had, as he put it, got “Brexit done”, Mr Johnson conceded something no British prime minister in 100 years would ever have given away. In a few hours in October 2019, in a meeting with the then Irish prime minister Leo Varadkar, Mr Johnson announced that he would put a customs border in the Irish Sea. It separates England, Scotland and Wales from Northern Ireland, resulting in Northern Ireland being treated almost as if it were still in the EU.

As someone with family roots in Northern Ireland, mostly among the Protestant and Unionist community, I was stunned. I was visiting Belfast the day after Mr Johnson’s extraordinary decision. Unionist friends told me they were utterly flabbergasted and angry, as one put it “that 100 years of Ulster unionism has been thrown in the Irish Sea". Another said that Margaret Thatcher always insisted that Northern Ireland was as British as her London constituency of Finchley, whereas Mr Johnson had made Northern Ireland “as British as France".

Events have consequences. Since that decision in 2019, Mr Johnson set a self-imposed deadline to conclude his Brexit deal, and Unionists in Northern Ireland have become increasingly unsettled. Food to Northern Ireland supermarkets was held up in new bureaucratic checks.

As I reported some weeks ago, even buying garden plants from growers in Scotland or England ran into new customs regulations, new form filling, new bureaucracies. The message to Unionists, mostly from the Protestant community, has been unsettling: you are not as British as you think you are. The "integrity of their quarrel" has awakened Northern Ireland's fears like a sleeping monster from the past. Opinion polls suggest increased support in Northern Ireland for a referendum to join the Irish Republic.

There have been other destabilising rows about the police in Belfast not stopping mourners gathering at the funeral of a well-known former member of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). That is the group that mounted the campaign of terror against Britain for some 30 years until the Good Friday Agreement was signed.

I lived in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, as they were called, and I knew people who were murdered in the violence. I now fear the carelessness and consequences of Mr Johnson’s decision. Perhaps someone should read to him the end of Churchill’s 1922 speech: “It says a great deal for the power which Ireland has… upon the vital strings of British life and politics, and to hold, dominate, and convulse, year after year, generation after generation, the politics of this powerful country.” It is Mr Johnson’s Brexit mess. It is convulsing another generation. He needs to clean it up.

Gavin Esler is a broadcaster and UK columnist for The National