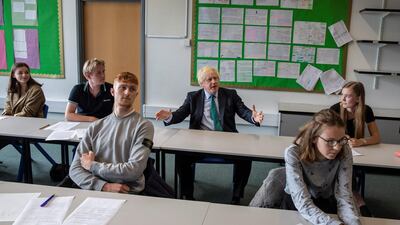

Britain in 2020 is a peculiar place. We are having an argument over an ancient piece of poetry in a patriotic song, “Rule, Britannia.” Written in 1740, the words include the idea that Britons “never never never shall be slaves,” but the verse was written at the peak of the slave trade, and there is an enormous row – inflamed by Prime Minister Boris Johnson as a distraction from his multiple policy failures – over whether to sing “Rule, Britannia” in a concert in the Royal Albert Hall.

Rather than wade into the politics of distraction, I am much more interested that the “Rule, Britannia” row comes as the study of poetry in England – the home of so many great poets – is being hit by a wrong-headed decision of the education authority known as “Ofqual,” the Office of Qualifications and Examination Regulation. Ofqual decided that next year, school children will no longer have to study poetry in order to pass exams in English literature. This is daft. Poetry is not for everyone. It can be difficult and off-putting. But so can algebra, geometry and the use of the subjunctive when speaking Spanish. And poetry is also extremely popular with children. According to the Children’s Literacy Trust reading and even writing poetry engaged half the children they surveyed. Poetry is often recited on TikTok and shared on other social media. Children love to play with words and enjoy making patterns of rhythm and rhyme.

As a teenager I was encouraged to recite poetry by heart. One favourite was “On His Blindness” in which the 17th century English poet John Milton laments his loss of eyesight, trying to understand why his one great gift – writing – is “lodged with me useless”.

Later I was introduced to the works of the 13th-century Persian poet Rumi who followed Arabic models in writing, as did Omar Khayaam in his Rubaiyat, using a literary form which another poet, Sa'ib, says "thrusts the fingernail into the heart." He's right. It does.

This decision by a few Ofqual bureaucrats is supposed to be temporary, but it is also revealing of a mindset of educational defeatism – the belief that children will choose what they think is easy over something supposedly difficult. But how can anyone know whether poetry is difficult unless they study it first? Why – except for administrative convenience – not insist all children study a literary form found in all cultures and all ages?

From Japanese haiku to Persian and Arab verse to Goethe, Homer, Virgil and Wordsworth, to beautiful poems celebrating the world’s great religions, poetry will survive this bureaucratic blunder.

But what is at risk is that some children may miss out on enjoying the complexity of meaning in verse and the music of sounds and rhythm fitting together – a complexity which, you may conclude, underpins the row about the precise meaning of “Rule, Britannia”.

What is clear is that from the nonsense poetry of Edward Lear to the sharp lyrics of hip hop or country ballads, Shakespeare’s sonnets or patriotic but controversial songs, the inventive poetic arrangement of language will always move the spirit, inspire and touch the soul. And teachers know how to teach it.

My own English teacher very cunningly persuaded my (somewhat reluctant) class of 13-year-olds that compulsory lessons on poetry were worth our time by opening a lesson playing songs by Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan.

This was followed by the lyrics of some less distinguished pop songs. We discussed what the words meant and then were inspired to read other kinds of poetry. I thought of that inspiring teacher years later, in 2016 when the Nobel Prize for literature was awarded to Bob Dylan for, as the Nobel committee put it, "having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition."

Rolling Stone magazine voted Dylan the greatest song writer of all time. Accolades from a music magazine to the Nobel committee suggest something worthwhile is being created by poetry which spans high art and popular culture.

And so perhaps the decision to make the study of poetry in England voluntary rather than compulsory may not be such a big deal. If you have ever instructed a teenager that something is not for them, you can be sure they will see it as a clear incitement to do the opposite, and jump into poetry.

The bizarre row over “Rule, Britannia” comes as Mr Johnson’s government faces one of the worst economic slowdowns in any rich country, one of the worst records on coronavirus in Europe, and amid concerns that his plans for Brexit will be implemented incompetently. Even if “Rule, Britannia” is as out of date as the British Empire sending gunboats around the world, poetry, like the human spirit, will win in the end. Bureaucrats and desperate political leaders can’t kill this common human need.

As that great American poet Maya Angelou put it, “You may tread me in the very dirt / But still, like dust, I'll rise.”

Gavin Esler is a journalist, author and presenter