Spread out on a table by US Homeland Security staff, the collection of 590 ancient Egyptian artefacts was a treasure trove of antiquities – including gold amulets, figurines and tablets.

Suspicious customs officers at New York’s JFK Airport had been met by the smell of wet earth the moment they undid the bubble-wrapped items. Sand and loose dirt spilt out, all "indicative of recent illicit excavation".

The passenger who brought them in suitcases from Cairo to the US, Ashraf Eldarir, insisted they were family heirlooms and he had paperwork in Arabic to prove his grandfather was an antiquities collector in the 1920s.

Eldarir's story failed to convince and he now faces up to 20 years in prison when he is sentenced in June, after admitting to four counts of smuggling. But his tactic, using fake provenance documents in the hope of convincing buyers that the items were discovered decades ago, set experts on the hunt for other relics that he may have sold.

An investigation by The National has uncovered that an artefact the British Museum bought from a convicted smuggler, as reported previously, was supposedly from the collection of Eldarir’s grandfather. It has led to questions over whether the institution had fallen for what one archaeologist dubbed the “dead dad provenance” trick, or “grandfathering”, as it is often known in the trade. The seemingly trivial purchase, for just $400, could prove embarrassing for the museum.

“Anyone can fake an old document and use whatever names they want on them,” said Paul Barford, a British archaeologist who researches artefact hunting and the market for antiquities. “I’d take that with a huge pinch of salt unless there was independent evidence to support it.”

Shabti sale

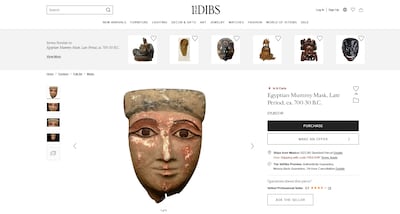

The shabti, or figurine, now belonging to the British Museum is described as having “eyes with heavy lids and an unsmiling mouth” and a rare combination of attributes. The museum does not mention that it was bought from a convicted smuggler.

According to the ownership history on the museum’s website, the shabti was bought in Egypt in 1946 by Ezz el-Din Taha El Dharir, and then taken to the US two years later. Ezz el-Din is Ashraf Eldarir's grandfather and his name is more commonly transliterated as Ezeldeen Taha Eldarir.

The museum's website says that “in 1948, the two shabtis and many other Egyptian antiquities travelled from Cairo to Brooklyn, where they have remained within the family ever since".

The notes state it was sold in 2017 by “Dr Ashraf el-Dharir, a collector resident in Brooklyn”, using a different transliteration from Arabic of Eldarir’s name, to antiques dealer Morris Khouli, who runs the Palmyra Heritage Gallery in New York. In the latter half of that year, there were at least two Palmyra auctions featuring Egyptian antiquities from the “el-Dharir collection”.

Khouli is a convicted smuggler who also tried to use the dead dad trick when he offered a US collector two Egyptian antiquities he falsely said came from his father’s collection.

Regarding the shabti’s provenance, the museum's website states: “Morris Khouli of Palmyra has sent scans of a four-page Arabic document recording the family’s original purchase of 125 antiquities, including both shabtis, on 3 November 1946. The buyer, an ancestor of Ashraf, was Ezz el-Din Taha el-Dharir. The 1946 vendor is identified as a Salah el-Din Sirmali."

The museum adds that the item was authenticated at that time by an expert called Hussein Rashed, who is described as the head of a "House of Egyptian Antiquities".

Checkability

Mr Barford has been writing about both Eldarir and Khouli for a number of years. He questions why the museum has not looked at the original provenance documents.

"Where is the original of the document, what paper is it written on? Note that the museum only reports that ‘scans’ were ‘seen'," he said.

He is concerned that a provenance document can be easily concocted by a seller trying to account for how he came to obtain an item.

As well as fostering an image of legitimate purchase, the benefit of being able to say it belonged to a deceased relative allows sellers to get around rules introduced in recent decades to control the export of antiquities from Egypt, said Mr Barford.

He said the dealer is then in charge of the “checkability” of the information. “Unfortunately that person who had it earlier is almost always no longer around,” he said.

Angelika Hellweger, a lawyer and art crime expert, said: “What I find interesting is Eldarir seems to have used this statement that it was from a private collection because in 1983 Egypt introduced a prohibition on the export of antiquities without approval.”

Ms Hellweger, legal director at London's Rahman Ravelli law firm, added she "would not be surprised if Eldarir and Khouli, who are both collectors with a criminal past" had been in cahoots.

“Most buyers still do not ask any questions. They ask ‘is it real?’ and if something has a whiff of being illegally excavated, that is an additional argument for authenticity. It is as simple as that,” Mr Barford said.

He said the Unesco 1970 Convention, a treaty aimed at battling the illegal trade in cultural items, states that documentation accompanying artefacts should fulfil certain conditions. This followed a situation where for "years and years, antiquities were collected in a way that deliberately obscured where they actually came from".

"But dealers and collectors still refused to treat documenting origins with any seriousness and just chucked away receipts and shipping documents. Now we are beginning to take more notice and such ‘documents’ appear with dealers and collectors claiming they really had been curating them all this time. But how true is that?"

Museum in the spotlight

Chris Marinello, a leading expert in recovering stolen, looted and missing works of art, said items are often sold between dealers who already have probable customers lined up. Thorough questions are not always asked, he said, as “it’s a small community” and they “trust each other”.

He believes the British Museum should not have bought the shabti as the provenance was dubious. He suggested the museum should also tighten up their collection management procedures and security measures, pointing out that one of its curators was dismissed for gross misconduct in July last year after more than 1,800 items were found to be missing, stolen or damaged.

When The National contacted the British Museum about the shabti, it said the artefact has been the subject of a criminal investigation by the US authorities since 2019.

A request made under the UK’s freedom of information law to the museum to disclose the efforts it has made to establish the provenance of the shabti was rejected. It cited the exemption from disclosure due to the item being subject to law enforcement and legal proceedings.

The US Department of Homeland Security Investigations confirmed it has been conducting an inquiry but would not reveal any further details.

The museum says it is continuing to research the provenance of the object, is always willing to work with law enforcement and has engaged with US authorities to support inquiries.

“Establishing the provenance of an object is an integral part of the Museum’s acquisition process and this process undergoes regular review,” said a representative. "The most recent updates were in 2024 and ensure that the museum only acquires objects where it has undertaken satisfactory due diligence and made all reasonable enquiries.”

Mr Khouli has been approached for comment directly and Ashraf Omar Eldarir through his lawyer.

Rick St Hilaire, a cultural heritage lawyer, former chief prosecutor and past presidential appointee to the US Cultural Property Advisory Committee, points to the alarm bells that should ring for anyone checking the provenance of an artefact.

Mr St Hilaire said auction houses, major museums, owners, dealers and collectors must do due diligence.

“It starts with knowing the person you're dealing with. Second, listening to their story carefully. And it doesn't stop there. Get verifiable documents, photos and affidavits.

“Fake provenance is common, and the invention of tall tales is only limited by the imagination. In my experience, the bigger the tale, the more sceptical I am,” he told The National. "My rule is simple - if someone starts talking about their uncle’s dad’s brother’s stepson who found an object, I’m not buying it.”