To Mustafa Omar and his young family, Sudan’s brutal civil war meant more than fleeing Khartoum, it forced a dangerous journey to safety in a rural area and pushed him into the country’s burgeoning “gold rush” to make ends meet.

Goldmining in northern Sudan was perhaps the only option for the 43-year-old electrician in a country whose already fragile economy has been decimated by a war that left much of the capital in ruins, killed tens of thousands and created one of the world’s worst humanitarian and displacement crises.

His decision to take up goldmining is neither unique nor rare in today’s Sudan, where hundreds of thousands of men like him, desperate to provide for their families, took up the dangerous and physically demanding job in the resource-rich yet impoverished Afro-Arab nation.

“I have been doing this for two years, and now I want to go back to being an electrician and not looking for gold underground," Mr Omar told The National from Sudan.

"I long for the day when none of us, the Sudanese, must risk our lives to make a living.”

Gold production in Sudan has for years been a murky business, attracting adventurers, smugglers and foreign interests seeking quick profits. In several ways, the current gold rush is a by-product of losing most of the country’s oilfields when South Sudan seceded in 2011.

The civil war that erupted nearly three years ago intensified the scramble for gold, with many venturing independently and randomly into mining. Some estimates put the number of men involved at around two million. The National could not independently verify that figure.

Official figures place government revenue from gold exports at about $2 billion, but experts say smuggling and local use of gold outside official channels account for far more. In 2025, for example, Sudan’s gold production was around 70 tonnes, but only 20 tonnes were exported, with the remainder smuggled out of the country or treated locally in primitive refineries.

Foreign interest

Lamia Abdel Ghafar, Sudan’s minister for cabinet affairs, said the military-backed government is working on a strategy to "regulate" goldmining to "save lives, the environment and the sustainability of a key resource".

"The problem of smuggling remains, and the government is trying to stamp it out with the help of security forces,” she told a news conference earlier this month when she also disclosed that the government has reached agreements to export gold to both Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Sudan is considered one of Africa’s top gold producers, and Saudi Arabia appears ready to step in.

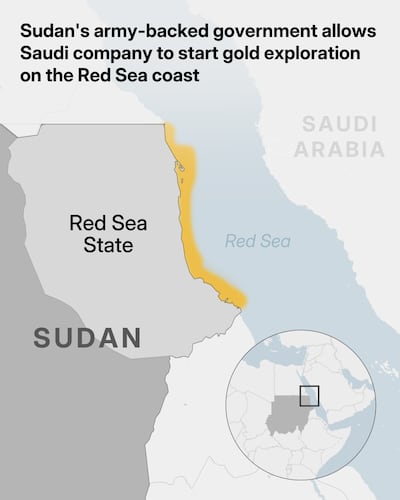

On Monday, the Sudanese Ministry of Minerals signed an agreement with the privately owned Saudi Gold Refinery to allow it to conduct gold exploration along the Red Sea coast. The deal will also involve geological evaluation and mining development.

Saudi Arabia has close ties with Sudan’s army, which has been battling the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces since April 2023.

"Saudi Arabia has been trying to make a bigger political and economic push into Africa for years, and Sudan is at the centre of this strategy," Gulf analyst Anna Jacobs told The National. "Over the last year, in particular, Saudi Arabia has stepped up its support for the Port Sudan-based government as the war with the RSF intensified. The kingdom is more concerned than ever about stability around the Red Sea."

Ms Jacobs said the region is important because Riyadh has a long Red Sea coastline, is increasingly alarmed by conflicts in the Horn of Africa and because many of Saudi Vision 2030’s flagship projects are located along the coast. "Stability in the Horn is both a national security and an economic imperative," she added.

Going underground for survival

While governments and investors eye Sudan’s gold, for many Sudanese, it remains a lifeline rather than just a commodity.

Mr Omar first secured his family in Al Duleq, an area about 100 Kms away from Khartoum, but still within the capital’s greater region. The area felt safer, and locals welcomed them. But the next challenge was just as daunting: how to afford food and rent.

His wife took a job as an assistant nurse at a local hospital, but her wages were insufficient.

“Our income was inadequate and fell way short of covering even our basic needs. I felt that I am shouldering a big responsibility,” said Mr Omar. “I headed to the goldmining area in the River Nile State where I joined friends. We initially stayed there for five months. The work was exhausting and harsh and the pickings were slim, but life was much less unbearable than being in the middle of a war."

A year later, things improved. Mr Omar bought a car and saved some money, but he does not want to continue goldmining.

Regional and international mediators continue to struggle to secure a lasting ceasefire. Both warring sides have been accused by the UN of war crimes and atrocities against civilians. This month, US senior adviser for Arab and African Affairs, Massad Boulos, announced a “Comprehensive Peace Plan” for the country, but the rival generals have yet to agree.

Last month, Sudan's army chief and de facto leader, Gen Abdel Fattah Al Burhan, said there would be no peace in Sudan until the elimination of the RSF.

Sudanese economist Mohammed El Nayer predicts that Saudi Arabia will become the primary market for Sudan’s gold, along with Qatar, Turkey and the UAE. However, he counselled that exports could contribute far more to the formal economy if the state refinery is upgraded and private investors are encouraged to build additional facilities.

“Still, the sector has made up for most of the revenue lost when the south went its way along with its oil,” he said.

In November, the UAE revealed that the value of its gold imports from Sudan reached $1.97 billion in 2024, accounting for 1.06 per cent of its total gold trade.

According to Sudanese central bank data, the UAE imported most of Sudan's gold exports, about 8.8 tonnes, in the first half of 2025. Some elements in the Sudanese authorities have accused the UAE of backing the RSF, mainly to secure gold, an allegation the country has strongly denied.

Amanda Marini, a Middle East analyst, said the decision of Saudi Arabia to "initiate direct purchases of Sudanese gold, with the objective of structuring a new African commercial hub and redirecting flows historically concentrated in Dubai, should be understood as part of a geoeconomic strategy of international insertion led by Riyadh".

"Saudi Arabia’s interest in Sudan’s mining and gold sectors cannot be reduced to a mere commercial transaction. What is at stake is a complex web of interests connecting maritime security, trade routes and intra-Gulf relations," she added.

Another relevant dimension, she noted, is that, since 2015, Saudi foreign policy has incorporated economic instruments as central vectors of power. "In Sudan's case, influencing or controlling segments of the mining sector also entails acquiring indirect leverage over domestic actors, particularly in a context of state fragmentation, where mining and gold are deeply intertwined with military and paramilitary networks," said Ms Marini.

'Live with dignity'

Back in Sudan, Hashem Mansour, another Khartoum resident, headed to the same goldmining area – Abu Hamad, north of the capital – as Mr Omar, but he made the journey soon after the 2018-19 uprising that ended with the ouster of dictator Omar Al Bashir.

Mr Mansour, a university graduate, was motivated by economic hardship and the desire to make his family comfortable.

“I spent a whole year away from my family when I first started. I have achieved what I set out to do; I bought a car, built a house and got married,” he said. “I chose goldmining because I looked for an opportunity to live with dignity and change my reality.

“I wanted to secure a future for myself. It’s a demanding job and sometimes even dangerous but making a living is never easy.”

Al Shafie Ahmed contributed to this report from Kampala, Uganda.