When Cherien Dabis’s All That’s Left of You premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January – one of several Arab films at the festival – it marked both a beginning and an ending.

Dabis broke through at the Utah event in 2009 with Amreeka, a project developed at the inaugural Rawi screenwriters’ lab in Jordan, founded by Robert Redford’s Sundance Institute in partnership with the Royal Film Commission. As the film world mourns Redford, who has died, aged 89, Arab cinema now stands as one of Sundance’s constants.

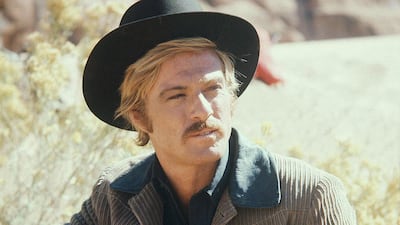

Redford’s only film touching the Arab world was Spy Game (2001), where Beirut served as the backdrop for CIA operations. But the actor – celebrated for roles in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Sting and All the President’s Men and who also directed nine features including Ordinary People – built something different for the region: infrastructure linking Arab filmmakers to Hollywood.

The Sundance Institute, founded by Redford in 1981, became a crucial door for Arab directors. In 2005, the launch of Rawi paired regional writers with international mentors.

Amreeka premiered alongside Najwa Najjar’s Pomegranates and Myrrh at Sundance in 2009 – both films emerging from Rawi’s first years. Amreeka, a drama about Palestinian-American migration, competed in the US Dramatic Competition, while Pomegranates and Myrrh, a love story set in Ramallah that had its world premiere in Dubai in 2008, screened in a non-competitive section. Suddenly, stories rooted in Ramallah and the West Bank were reaching distributors in Los Angeles and London.

Momentum built quickly. Mohamed Al-Daradji’s Son of Babylon was screened at Sundance in 2010. Sally El Hosaini’s My Brother the Devil won the World Cinema Cinematography Award in 2012. A year later, Jehane Noujaim’s The Square captured Egypt’s revolution and Sundance’s audience award before earning an Oscar nomination – the kind of trajectory that had been impossible for Arab documentaries before Sundance opened its doors.

“I could see and feel that there were other voices out there,” Redford said in 2018, explaining Sundance’s origins. “Other stories that needed to be told that were maybe more risky. They weren’t being given a chance.”

He may have been describing American independent films, but the words applied just as well to the Arab filmmakers his institute would champion.

Beyond screenings, Sundance provided vital financial backing to Arab and North African filmmakers. Its Documentary Fund supported Noujaim’s work and Talal Derki’s Return to Homs, which won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize in 2013. Derki returned with Of Fathers and Sons, which premiered at Sundance in 2017 and was later nominated for an Academy Award.

Sundance’s labs and residencies – the workshops and extended retreats it designed for filmmakers – connected Arab directors to producers and distributors, helping them strengthen scripts and secure more festival invitations and distribution opportunities.

By 2019, when the documentary Gaza premiered at Sundance, Arab films were becoming a mainstay. The film’s subjects, including musician Abu Yaseen, were invited but denied exit permits by the Israeli government. The film screened without them – a reminder of how freedom of movement is taken for granted by many, but also of how the voices of the disenfranchised can still reach the world.

The Arab world recognised Redford’s contribution directly. In December 2019, he received the Etoile d’Or, a lifetime achievement award, at the Marrakesh International Film Festival, where he described his career as a “lifelong quest for truth and freedom”.

It underscored the contrast between Spy Game’s Beirut backdrop and the Palestinian stories Sundance championed: Hollywood often used the Arab world as scenery, while Redford helped build systems that let Arab filmmakers tell their own stories.

Redford leaves behind more than 75 film appearances and nine directorial works. In the Arab world, his legacy remains in the Jordanian lab that nurtured a generation, the Palestinian dramas that reached Utah, and the Arab films that continue to screen at Sundance – proof that the doors he opened remain wide.