The title of Greatest Living Critic is a lofty one, a prestigious label in the world of letters, but one that James Wood has worn relatively humbly for the past decade. As with the best of his forebears, he routinely divides opinion, and yet admirers and detractors seem to be united in their admiration for his fruitful and insightful yields from gimlet-eyed close-reading, and his penetrative ability to get to the core of a novel. It has led fellow critic Cynthia Ozick to appeal for a "thicket of Woods". As one has yet to materialise, we should instead appreciate what we have and hope for a continued, consistently excellent output of literary appraisals and takedowns of both contemporary and classic fiction.

Four years on from Wood's astute primer, How Fiction Works, and we are now due another book. The Fun Stuff is a much-welcome collation of 23 discerning essays and reviews on authors and oeuvre. Whereas earlier collections had their contents linked by a unifying red thread - The Broken Estate and The Irresponsible Self could be decoded by their subtitles: Essays on Literature and Belief and On Laughter and the Novel - The Fun Stuff is simply a best-of compilation of dispatches for The New Yorker, TheNew Republic and the London Review of Books between 2004 and 2011. There is no binding theme, and the arrangement, though chronological, seems in places a flung-together hodgepodge (an essay on Geoff Dyer following one on Thomas Hardy); but, as most of the authors included are still writing, we can view it as an in-depth study and commentary on the modern novel.

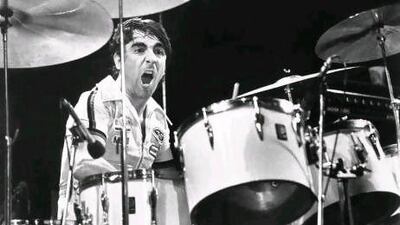

That said, the first, eponymous essay is the odd one out. The Fun Stuff is an homage to The Who's Keith Moon and an autobiographical account of Wood's history of, not to mention talent for, drumming. Wood reveals his "sheltered, austerely Christian upbringing" and how he "got off on classical and churchy things". His interest in theology informed his first book of criticism (and flavoured his novel, The Book Against God - proof that not every critic is a novelist manqué) and that scriptural knowledge (and scepticism) seeps into several essays here. Cormac McCarthy's The Road highlights the book's eschatological plot, godless presence and "dilemmas of theodicy"; the novels of Marilynne Robinson, Wood argues, are infused with the author's own "founded ecstasies" and enriched by polarising meditations on faith. There is even an essay on religion, specifically the King James Bible. Theological thought imbues certain literary pieces, and in a similar vein Wood weaves literature into his musical essay. Keith Moon's "formally controlled and joyously messy" drumming is apparently akin to the more frantic sentences we see in DH Lawrence, Saul Bellow and David Foster Wallace.

Wood is a master at such blending. Each essay contains numerous voices, not only that of the writer under discussion. Other writers, philosophers and critics are referenced or quoted to validate a point or attest to a certain heritage or tradition. Wood expands each review by beginning with a salient theme and then illustrating his chosen author's relationship to it. Thus the McCarthy review is prefaced with a brief discourse on the post-apocalyptic novel; the lead-in to a review of Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go expounds on the tricky knack of fusing literary fiction with sci-fi or fantasy.

However, Wood imports too much outside noise in a review of Joseph O'Neill's Netherland. What begins as a reading of the book as a postcolonial novel ends up a critique of Zadie Smith's misreading of it, resulting in her review being allotted the same review space as O'Neill's novel.

The two longest works here, essays on George Orwell and Edmund Wilson, show Wood's adroitness with quantity and quality. The former was lauded by the late Orwell aficionado Christopher Hitchens. The latter is redolent of an earlier essay on Harold Bloom, in which Wood demonstrated his fearlessness at taking on an acknowledged heavyweight. Bloom for Wood is past his prime, repetitive, keen to rank, and perhaps most scathing of all, no longer a critic but "a populist appreciator". Wilson comes off better and is lauded for his "pugnacious clarity" but is faulted for eschewing close textual reading. Wood follows in the tradition of Matthew Arnold and TS Eliot (and even Bloom) by favouring an aesthetic approach to literature and for isolating key chunks of text to pan for both beauty and meaning.

Wood is equally efficient and just as renowned for his turn of phrase. It is here, though, that we find his strengths and weaknesses. On the plus side, his quirkier descriptions always hit the mark: the reader grows sated with Norman Rush's language "as houseguests sometimes want to escape their overvivid hosts"; Aleksandar Hémon is "a postmodernist who has been mugged by history". Wood's metaphors stay resolutely unmixed: Ishiguro's characters' "freedom is a tiny hemmed thing, their lives a vast stitch-up"; Orwell, bringing his description to already extant fictional worlds, "needed a drystone wall already up, so that he could bring his mortar to it and lovingly fill in the gaps". At times his descriptions are necessarily stark, and calling VS Naipaul "the public snob, the grand bastard" gets us straight to the point.

But Wood is deaf to his more flowery, overwrought phrasing, and clearly no editor is prepared to take a red pen to such ornamental flourishes. An essay on Anna Karenina in The Irresponsible Self contained, for my money, his worst example (Tolstoy is "a beast of instinct who can outrun the nervous zoologists of form") and in this collection he continues to veer from the baroque (Gogol didn't hide his plot, he "garaged his secret") to the nonsensical (schoolchildren have large musical instrument cases strapped to them "like diligent coffins").

Several essays in The Fun Stuff also exhibit uncharacteristic erratic displays of conviction, to the extent that we require a leap of faith to believe in Wood's argument. Orwell "almost certainly got this eye for didactic detail from Tolstoy"; Ian McEwan "may be aware that Rousseau hovers behind him", and "Graham Greene and George Orwell may have been closer models" for him; "what [Dostoevsky] probably liked about Eugene Onegin was its utter absence of rational motive". The "certainly" is Wood overstating his case, and with the modifying "may" and "probably" he is timidly hedging his bets.

However, these are rare lapses. Elsewhere, and shorn of these shaky props, he excels and convinces with carefully substantiated arguments, in turn subtly theorising and forcibly ramming his points home. Wood is immensely, omnivorously well-read (in the Hardy essay, he seems to have devoured not only his fiction but also all poems, letters, notebooks and biographies), able to connect an idea with that of a like-minded literary antecedent. A line by Ishiguro is linked to a Kafka story and then to one by Beckett, from which we bounce to Hardy's Tess before culminating in a similar line in a Hardy poem. The result is like watching dexterously skimmed stones, only each ripple never diminishes in size.

In recent years, Wood has been criticised for a steadfast avowal of realism over all other schools of literature. In Joseph Anton, Salman Rushdie dubs him "the malevolent Procrustes of literary criticism" for his inflexibility towards other genres, chiefly Rushdie's magical realism. The Fun Stuff doesn't do a lot to level that lopsidedness (an essay on Paul Auster is in effect a hatchet job on Auster's shallow prose) but there is an illuminating piece on the avant-garde fictions of László Krasznahorkai and WG Sebald gets his due for inheriting Thomas Bernhard's "diction of extremism".

In How Fiction Works, Wood argued that "the novel is the great virtuoso of exceptionalism: it always wriggles out of the rules thrown around it." Wood is also a virtuoso of exceptionalism in that he has, at present, as a critic, no equal. It wouldn't be too great an exaggeration to subtitle The Fun Stuff - How Criticism Works. But how it works and how it is done are two separate matters. I doubt even Wood can articulate how he does it. The fact is, he can do it, and after all this time he still remains at the top of his game, with no one quite tall enough to snatch his crown.

Malcolm Forbes is a freelance essayist and reviewer.