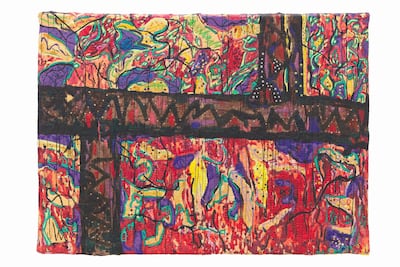

Sixteen years after her death, artist Pacita Abad’s extraordinary tapestries and paintings are being rediscovered. Abad created a technique she called trapunto, which she borrowed from the Italian word for quilt.

Travelling the world, she picked up different sewing and fabric techniques, incorporating these into vast tapestries that spoke of the global fight for social justice: the immigrant experience in the US, Cambodian refugee camps on the Thai border, the 1998 riots in Jakarta following the devaluation of the Indonedian rupiah.

By the end of her life, she had produced an estimated 4,000 to 5,000 works, which up until a few years ago were sitting rolled up in a warehouse by Dulles Airport in Washington.

"She took the technique of quilting from an American friend," her nephew, Pio Abad, tells The National. "But what makes it her own is the endless level of embellishment, and how she adapted the techniques to her own ends."

A recent revival of interest in her work began with a 2018 show at Manila's Museum of Contemporary Art and Design. Today, Pio and Pacita's husband, Jack Garrity, are undertaking the near Sisyphean task of cataloguing her work, and putting together an exhibition of her work, to be held at the Haus Der Kunst in Munich.

Abad’s first European exhibition, titled Life on the Margins, was co-curated by Pio and held in Bristol in the UK. It only recently came to a pause after museums and galleries closed amid the coronavirus outbreak.

The show had been drawn from one of her later works, made when she was struggling with lung cancer at the end of her life. There, confined to her bedroom, she continued to sew together bits of printed fabric and old paintings that she had made before, and embellishing them with stones, sequins, ribbons, shells and mirrors to create tall, scroll-like tapestries. The abstraction recalled the type of work she had made at the beginning of her career, in the late 1970s, when she started stitching and stuffing canvases and turning them into unique tapestries.

She was born in Batanes but lived around the world

Abad was born in 1946 into a family of 14 in Batanes, in the north of the Philippines. Her father was a Congressman, and her nephew says she was groomed to be a lawyer or in Congress herself. But she left the Philippines for good in 1969 to pursue a PhD at the University of San Francisco. She never finished; instead she met her future husband, Garrity, and the couple decide to hitchhike overland from Turkey to the Philippines.

Her life was designed to be spread across the globe Garrity became an economist for the World Bank, and the pair lived and travelled across Sudan, Bangladesh, Japan, Guatemala, Singapore, Indonesia, India and the US.

Pio, who teaches at Goldsmiths College, University of London, is a well-respected artist in his own right and recently exhibited at the Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai.

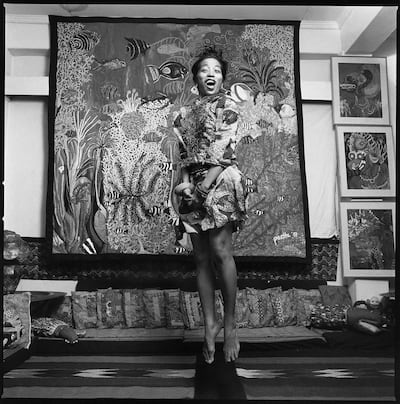

He describes his aunt as a woman suited more to aesthetic exuberance than legal word-sifting. For the opening of an exhibition in 1984 at the Museum of Philippine Art in Manila, for which she’d created acrylic paintings inspired by Philippine sea life, she arrived in full scuba gear, with mask, bathing suit and fins. “She was one of a family of 14,” Pio laughs. “You had to learn to stand out.”

How she used her work to shed light on the experience of global migration

But the politics of her family remained embedded in her, and she was deeply committed to social justice. She worked with different activist groups and international aid groups on the Thai-Cambodian border during the time of the Cambodian genocide, and used her paintings to shed light – in both form and subject – on the experience of global migration, particularly in the US.

Chiefly made while she was living in Washington in the 1990s, her Immigrant Experience series, based on people she knew, addresses life among new arrivals to the US, revealing the many ethnicities that are swept up in the category of "immigrant" or simply "non-white".

In the same way that she integrated different techniques into her tapestries, her works celebrate the diversity of the US: two figures buying groceries from a market in Korean Shopkeepers (1993), a tapestry of incredible detail in which she made papier-mache strawberries and covered them in red wax. In If My Friends Could See Me Now (1991), she stands with her arms crossed, looking nonplussed, as behind her the panoply of life in the US stretches out: grey urban streets, lighted city windows, a well-proportioned suburban house with a white picket fence. The words "American Dream" are emblazoned across the tapestry.

L A Liberty (1992) is the masterpiece of this series – and indeed of the show. The work reimagines a woman of colour, in many senses of the word, as the Statue of Liberty – as an immigrant, as well as one swathed in colours.

Fabrics in red, blue and purple radiate upward from the figure’s crowned head; the folds in her tunic have been rendered as a patchwork of different patterns, each embellished in its own way with sequins, buttons and gold threads. She looks beatific, and also slightly challenging.

In an interview at the time, Abad said she made L A Liberty for those who did not come to the US in the country's most famous time of immigration, in late 1800s, but for the Asians and Latinos who came from the east or the south, and who had not passed through the former processing centre at Ellis Island, home to the Statue of Liberty. The idea of the US as a nation of immigrants was formed during that late 19th-century period, and afterwards sympathy towards migrants largely closed.

“During the past two decades the United States has become an increasingly multi-ethnic society, with a fabric of nationalities that combines many threads of all sizes and colours,” Abad said at the time. “The continuing increase in legal and illegal immigration has caused great concern, and many Americans question whether immigration should continue, and whether it is possible to balance order, community and unity within the rapidly changing ethnic landscape. It was because of these issues that I decided to do something to give people a better understanding of the immigration experience.”

South to south encounters

Pio also notes that Abad’s work mapped what is now known as South to South encounters – or the network of developments communities, solidarity movements and migrant labour during the late 20th century that many artists and academics are now exploring.

Her portrayals, for example, of the riots after the devaluation of the Indonesian rupiah in 1998 are part of a larger history of exchange between Indonesia and the Philippines.

Her incorporation of different craft techniques from the countries she visited was also informed by her identity. “What enabled her to access all these communities was in one sense that she was a diplomat’s wife,” Pio explains, referring to the stereotype of the privileged woman who takes up art-making as she follows her husband around postings. “But she was also a brown person. She would have conversations that might not otherwise have been possible.”