"When I was a child I had lunch at my grandparents place every other Sunday," Lebanese artist Rayyane Tabet says. "They lived in a large, cold apartment and showed their affection in a rather restrained manner, so I spent most of my time sitting in a chair trying to behave.

From there I could a see a photograph of a man. He didn't look like anyone in my family, and in my grandparent's library there was a yellow book, written in German, a language no one in the family could understand."

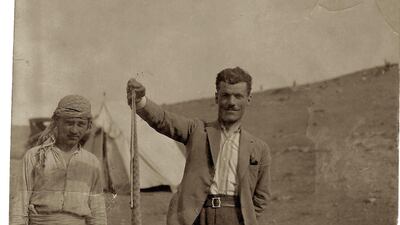

Years later, as Tabet was helping to empty his grandparents' apartment, he stumbled across several keepsakes that connected his great-grandfather, Faek Borkhoche, to this mystery man, whose name was Max von Oppenheim. He was a German diplomat who had become an amateur archaeologist.

In the apartment, Tabet found photos of Von Oppenheim and his great-grandfather in Tell Halaf, a Syrian village on the border with Turkey and home to the Kapara Palace, a Neo-Hittite site that was uncovered by Von Oppenheim before the First World War. Tabet began researching the site and discovered that a combination of geo-politics and tragedy meant 194 reliefs – carvings in which the design stands out from the surface – from Tell Halaf, each more than 3,000 years old, ended up being scattered between seven museums across the world.

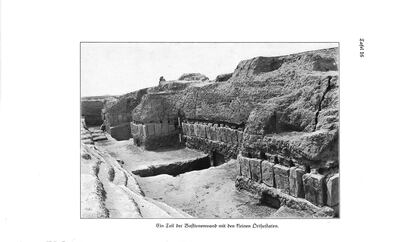

"In 1899, Oppenheim was sent to Baghdad to chart a possible railroad," Tabet says. "Stopping in Tell Halaf [in Syria], he was told by the Bedouins of gods, demons and monsters hiding underground, in the hopes this foreigner would help unearth the statues.

Between 1911 and 1913, he discovered an entire city hidden beneath the plains and a Neo-Hittite palace, with 194 reliefs made of black basalt and red-painted limestone. The First World War started before Max could finish documenting them, but he returned in 1927 and spent two years finishing the excavation."

How many of the thousand-year-old pieces were bombed and then rebuilt

After the war, 35 reliefs were given to France, who donated them to Aleppo, where the pieces entered the city's National Museum. Von Oppenheim failed to sell his share of the artefacts to the Pergamon, the most visited museum in Germany, but as the heir to a banking fortune, he used his incredible wealth to open his own museum in Berlin, the Tell Halaf Museum, where he could display them. "In 1943, a British fire bomb hit the Tell Halaf Museum, destroying all of the objects inside, including 12 reliefs, except those made from basalt," Tabet says. "The cold water thrown by firefighters shattered the objects into 27,000 pieces."

Von Oppenheim packed the rubble into crates, hoping to restore it later, and asked the Pergamon to store the pieces temporarily. But he died a year later in Bavaria, and when Germany was divided at the end of the Second World War, a new border between East and West meant the burnt-out Tell Halaf Museum and the Pergamon were on opposite sides of Berlin.

"Nothing could be done until the reunification of Germany in 1991, when a loan agreement was made between Von Oppenheim's family and the Pergamon, allowing conservators to restore the Neo-Hittite palace sitting in their storerooms," Tabet says. "They spent 15 years rebuilding 26,000 of the 27,000 pieces into about 30 sculptures, architectural details and 59 reliefs."

Where did the rest of the reliefs end up?

Tabet has traced the fate of the other reliefs. He discovered that, in 1913, Von Oppenheim tried to ship 15 to Berlin via Alexandria, where the British Navy seized them as enemy cargo during the First World War. In 1920, the reliefs entered the British Museum's collection. In 1927, 61 reliefs went missing from Tell Halaf and are still unaccounted for. Then, in 1930, 82 reliefs were shipped to Berlin as part of Von Oppenheim's share from the Tell Halaf excavation, three of which he donated to the Louvre in Paris.

Von Oppenheim tried to sell eight reliefs in New York in 1932, but couldn't find a buyer after the market crash, so he left them in storage and returned to Berlin. In 1942, US president Franklin D Roosevelt issued an executive order to establish the Office of the Alien Property Custodian. That meant that any objects on American soil that belonged to US enemies could be seized and auctioned, with the eight reliefs shared equally between New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art and Baltimores' Walters Art Museum. One relief from the National Museum of Aleppo was also donated to Syria's Deir ez-Zor Museum in 1974.

In 2016, one of the reliefs not yet accounted for appeared on the market and was bought by the Louvre. It was meant to have belonged to the great-grandson of a French soldier stationed in Tell Halaf during the First World War.

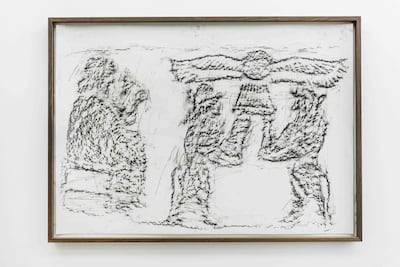

Of the 194 reliefs, 121 are now divided between Berlin, Paris, London, Baltimore, New York, Aleppo and Deir ez-Zor. "I started getting in touch with these museums, asking them if I could create rubbings of the reliefs in an attempt to reunify an object that can never be brought back together," Tabet says. "I've made 32 rubbings. I'm now in touch with the British Museum and will do the rubbings at the end of this year, while I also hope to go back to Syria to continue my quest."

Pulling together his great-grandfather's story

Two years ago, Tabet began showing his work at various galleries across the world, with an explanation of the fate of each relief written along the top. The Louvre is hosting the Forgotten Kingdoms exhibition until August 12, a show that focuses on Neo-Hittite and Arab civilizations, and is displaying some of the Tell Halaf pieces. It was the first time Tabet was able to display one of his rubbings alongside the original artefacts.

"I'm currently preparing for a show at the Metropolitan Museum in October," he says. "We're going to show my rubbings, borrowing the architectural language from the original site."

Despite the complicated story he discovered, for a while Tabet could only ponder one question: how was his great-grandfather involved? Tabet eventually found Borkhoche's diary from 1929 in a Cologne bank vault, which helped to fill in the gaps.

"He was sent by the authorities of the French Mandate in Lebanon to be Von Oppenheim's secretary and translator, but also to spy on him," Tabet explains. "The French thought Von Oppenheim was sent, disguised as an archaeologist, to make a map on the region.

"Before leaving in 1929, the Bedouins of Tell Halaf gave my great-grandfather a 20-metre rug. In his final will he said the rug should be divided into five pieces, one for each of his children, with the provision that they divide their pieces among their descendants, until one day the rug disappears." The rug has been divided into 23 pieces.

While preparing for his Met show, the symmetry between the fate of the rug and the reliefs struck Tabet. "Objects start as a whole and slowly get divided, dispersed and destroyed, so that they will never be whole again," he says. "Fragments, somehow, are more important than the whole."