DEIR AMMAR // Mahmoud Eid can recall the exact moment his life changed forever. It was about 10am on January 25, 2008, as he and his wife Samira were watching TV. An alert flashed on the screen: a massive explosion in Beirut had killed a police officer in an apparent assassination.

"I knew immediately it was my son," said Mr Eid, 63. "My wife said: 'That's our son.' We could feel that it was Wissam."

Mr Eid got in his car and drove south from his home in Deir Ammar to the Lebanese capital, where his worst fears were confirmed. Wissam Eid, his 32-year-old son, a computer engineer and captain in Lebanon's national police force, the Internal Security Forces (ISF), had been killed in a car bombing, along with his driver and three others.

More than three years later, Mr Eid and his family are still seeking answers to who murdered their son. They join many others whose relatives were killed or injured in a series of attacks that followed the assassination in 2005 of the former prime minister Rafik Hariri.

Eid was a member of the Lebanese team working with the UN investigation into the Hariri assassination. He is credited with having uncovered an intricate communications network - through painstaking analysis of mobile-phone records - believed to have been used by those linked to the murder.

On Thursday, the Special Tribunal on Lebanon (STL) issued arrest warrants for four Lebanese men, two of whom are ranking Hizbollah members. On Saturday, Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Lebanon's Hizbollah, reiterated his position that no one connected with Hizbollah had anything to do with the Hariri murder.

Eid himself was killed in a carefully planned attack as his car drove up to a busy intersection, past a vehicle laden with explosives. Because of his work on the Hariri case, some have connected the killing to Hizbollah. Others have linked Eid's killing to other cases he was involved with. But, so far, no one has been arrested for his murder.

Both Lebanese police and the tribunal are investigating Eid's murder, said Major General Achraf Rifi, the general director of the ISF. "He was talented and brilliant. He played an important role in the Hariri case and other cases. He was targeted, it did not happen by coincidence or hazard," he said.

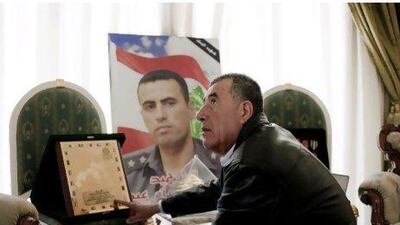

Mr Eid is hoping that his son's killers will still be found. "I just want justice for my son, for Hariri and the others," he said, seated in his living room.

At the entrance to Eid's town on the outskirts of Tripoli, two arches meet in the middle of the main road with a plaque dedicated to Wissam Eid alongside an etching of him.

At several points along the winding roads leading to the family home are large portraits of Eid in his police uniform, bearing the words: "The hero martyr" and "They killed the best man".

His memory permeates his parents' house, parts of which resemble a shrine to their son, the second of their five children. Photographs of a determined young man in uniform take pride of place in one of the living rooms, next to plaques and medals.

Mr Eid, a refined man who carries himself with the deportment of someone who also served as an ISF policeman for three decades, shuffled through dozens of framed certificates in his son's name: a secondary school diploma, university degrees and numerous awards.

"When he was young, if something was difficult to understand Wissam would always work until he got it," he said. "He always asked questions and he was very intelligent. He was always the first in school and university."

Eid, who his friends say had no overt political affiliation, had not initially planned to join the police force. After graduating with degrees in computer engineering, he moved to Doha to work for a telecoms company. But, just six months later, his father had convinced him to return to Lebanon to take up a position with the ISF information technology department.

"Wissam loved his work," Mr Eid said. "He did not work for any person - just for his country. But, he also discovered everything that was happening in this country."

Eid made headway not only on the Hariri case, but also on other important investigations into extremist elements in Lebanon, including Al Qaeda-inspired groups, Israeli spy-rings and the militant Fateh al Islam group. There had been previous attempts on his life, according to his father, and he had been badly injured during clashes with members of Fateh al Islam.

Azzam Sanjakdar and Roland Baz, two of Eid's best friends, speak of a highly intelligent, driven man; someone who they say refused to define people along religious lines.

"In the position he held, many people would have acted arrogantly, but the more Wissam got power, the more he did his best to serve people," said Mr Sanjakdar, 34, an electrical engineer who met Eid when they were teenagers and later lived with him in Beirut. "He was like my brother, my best friend."

Mr Baz met Eid when they were both doing their mandatory military service in 2000. The 35 year old, also an engineer, said: "Wissam represented the young Lebanese people who wanted to build the country. He didn't care about what religion you were, only your abilities. Killing him was a really cowardly thing to do. They didn't achieve anything on a political level."

Like Eid's family, Mr Sanjakdar and Mr Baz stress the need to find out who was responsible for their friend's murder. But, both acknowledge that any answers might be elusive.

"Wissam was very straightforward and wanted to serve his country, wanted to get to the truth and to reach the criminals wherever they were and whoever they were," Mr Sanjakdar said. "I believe there are very few people like him."

Major General Rifi stressed that the ISF is determined to find out who killed the man whose picture is among just four framed photographs propped up on a shelf next to his desk.

"We will find who killed him," he averred. "We are confident that we will arrive at justice."