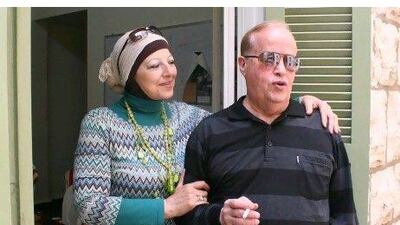

BEIRUT // Ghada Kaakani glances over with a smile as her husband recounts their first meeting in a Lebanese mountain village more than 40 years ago.

Bassam Al Hidiq was a Palestinian refugee in his twenties.

His family settled in the southern Lebanese city of Sidon after fleeing their home in Acre when Israel was created in 1948.

After what Mr Al Hidiq described simply as a "love story", they married and went on to have four children. Both say they were unaware of the challenges they would face as a family where the wife is Lebanese married to a foreign man.

"We were naive," says Mr Al Hidiq, now 67, as his wife nods in agreement, interjecting: "We didn't think of the practical things."

They included being able to provide their children with Lebanese citizenship at birth. The Al Hidiqs' two daughters are now citizens, having married Lebanese men. Their two sons are not and have only the travel documents issued to them as Palestinian refugees.

"It's not fair. I am Lebanese and it's painful," said Mrs Kaakani, 60. "The government must give me a passport for my children."

Lebanon's nationality law, which dates back to the 1920s, bars Lebanese women, unlike men, from passing their nationality to their children or spouses.

Estimates place the number of families affected by the law at about 16,000, but it is difficult to pinpoint an exact figure. Lebanon's last official census was in 1932.

Activists are hoping this all might change in the not-too-distant future.

Lebanon's cabinet discussed the matter last month and the government's National Commission for Lebanese Women, chaired by the first lady Wafaa Suleiman, drafted a bill that would allow Lebanese women married to foreign men to pass citizenship to their children. "First of all, we say no discrimination between men and women in granting citizenship to their children," said Fadi Karam, the commission's secretary-general.

The draft law envisions that after the age of 18, children of a Lebanese mother and father who is a Palestinian refugee registered in Lebanon would have a one-year window in which to apply for Lebanese citizenship.

The decision would be based on a set of criteria such as not being guilty of a criminal offence and having been resident in Lebanon for 10 consecutive years.

But, before this can happen, the proposed legislation needs to be reviewed and passed by the cabinet and then the parliament - a process Mr Karam concedes could take two years or more.

Lebanon's judiciary dealt with the issue in 2009 when John Azzi was the first judge to rule in favour of a family trying to apply for citizenship for the children of a Lebanese mother and foreign father.

His ruling was overturned by an appeals court, but he says that since the case, the debate has been reframed.

"For me as a judge, I make all judgments in the name of the Lebanese people and all Lebanese are equal in front of me," said Mr Azzi, who has written a book about this experience, A Journey of Life to Nationality. "Men and women in Lebanon should be treated equally in all matters," he said.

"I believe like the march of history all things will change, maybe not tomorrow, but after tomorrow."

Traditionally, the argument against such reforms in Lebanon has focused on the issue of the country's delicate sectarian demographic balance - there are 18 recognised religious sects and a delicate power-sharing system - as well as the policy of non-naturalisation of Palestinian refugees who maintain their right to return to their homeland.

However, Lina Abou Habib, the executive director of the Beirut-based Collective for Research and Training on Development-Action - which has worked extensively on the issue - dismissed the arguments as "simply ridiculous".

"There is no relationship between reforming the nationality law so that women have equal rights to men and denying the right of return to Palestinians," she said.

"For the demographic balance in terms of the confessional system, either we have to accept diversity and citizenship is based on citizenship rights not on affiliation, or demographics will always be used [as a political tool]. The rights of women do not in any way jeopardise any kind of balance."

Instead, Ms Abou Habib blames pervasive patriarchal beliefs as the reason Lebanese women continue to be denied the same citizenship rights as men.

"It is a situation where the state does not consider women as citizens, and one way in which you control women is to control their choices," she said.

"So you marry outside these choices, then you're an outcast and that is a way where the state - as part of that patriarchal system - controls women."

She said the recent progress on the issue has been "positive" - a sentiment echoed by Mrs Kaakani and her husband, Bassam. "Inshallah, they will change the law because these days they are talking about it a lot more," Mrs Kaakani said. "Hopefully the government is trying to make a change."