When Naresh Nil put out a casting call, he made his expectations very clear: “Wanted — dark or dusky models for a conceptual photo shoot.” But when the models turned up and he explained his project to them, he was met with reluctance.

Mr Nil, a 28-year-old photographer in Chennai, mostly shoots for fashion or retail industries. But once a year, he and his business partner try to push the boundaries with a project that reaches out to India’s social conscience.

“Once it was a short film on Labour Day and on India’s labourers. Another time, it was an a capella version of the national anthem,” Mr Nil said. “This year, we were thinking about these concepts of dark and fair skin.”

Indian society famously fetishises fair skin. The markets are awash with skin-whitening creams; the hottest models and movie stars are invariably fair; matrimonial advertisements make a point of listing pale skin as a desirable attribute, alongside employment status or educational qualifications.

Mr Nil diagnosed another problem. “Whenever we see these pictures of Hindu gods and goddesses, on calendars or on stickers or on posters, they’re invariably fair-skinned,” he said. ”So we figured: why not reverse this and compare dark skin to divinity?”

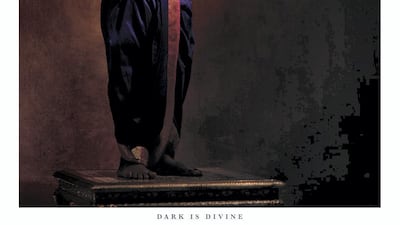

The resultant photo series, released online two weeks ago, features seven artfully composed images. In them, dark models — men as well as women — are shot in the poses and settings traditionally associated with Hindu deities.

The goddess Sita, from the Ramayana, plays with her two dusky young sons in a bucolic meadow. A boy Krishna, his swarthy chest bare, clambers onto a footstool and gazes at a pot of churned butter suspended just above his head. A saturnine Shiva sits in meditation, upon a tiger-skin rug, a snake coiled around his neck.

When Mr Nil explained these ideas to his prospective models, back in September, they backed out. “This is, after all, a religious theme, so they had their reasons,” he said. “Some thought their families would be against this. Others thought the project would be controversial.” The very people he wanted to feature, he found, had bought into India’s myths about fairness and darkness.

Traditions are difficult to defy. The most popular depictions of Hindu deities were painted by the artist Raja Ravi Varma more than a century ago; these depictions are now everywhere, on calendars and framed posters.

Even children’s literature pushes these notions. The popular Amar Chitra Katha series of comic books, which retells stories from Hindu mythology, invariably gives its noble gods peach-pink skin and its villainous demons an ash-black colour.

The “epidermal politics” of these comics are shaped by several aspects of Indian history, said Radhika Parameswaran, a media studies professor at the University of Indiana.

One factor relates to the Hindu caste system, of how the hierarchies of caste have been overlaid on to skin colour, Ms Parameswaran told The National. "Lighter skin colour is viewed as a status symbol for the middle and upper castes, who did not have to do manual labour."

British colonisation also played a role. “There is a general notion that whiteness does equate to capitalist, consumer, and scientific modernities, and certain kinds of achievements, like industrial and scientific advancements, are identified with Europeans,” Ms Parameswaran said.

In the modern era, she said, the glut of imported American media — movies, television shows and music videos — has further reinforced these “colourist” stereotypes. “In its own way, colourism could also instil ideas of white supremacy in Indian children — making them see people from Africa and African-Americans as inferior,” she said. “Colourism and racism are intertwined.”

_______________

Read more:

Cricket can help bridge India's caste divisions, researchers find

Pariahs no more — Kerala appoints its first Dalit Hindu priests

Low-caste Hindu leader Kovind sworn in as India's president

_______________

Devdutt Pattanaik, who writes popular books on Hindu mythology, pointed out that even when the epics describe a deity as dark-skinned, illustrations tend to avoid depicting them in that way. The Sanskrit word Krishna means "dark," referring to his complexion, Mr Pattanaik wrote in an article in 2009. “Somehow, an unnaturally blue Krishna was preferred over a naturally dark Krishna.”

For Mr Nil, these steep barriers complicated his project. When several of his models withdrew, he had to reach out to friends and family. One deity, a young Balamurugan - the god of war - was his sister’s son, standing stock-still and smiling. Another was the team’s make-up artist.

But the online reception to his project, he said, has made it all worthwhile. The photos have gone viral on Indian social media. “That was always the point — to reach as many people as possible,” Mr Nil said.

“The idea wasn’t to stir up controversy. It wasn’t to put down people with fair skin. It was only to ask a valid question: why should dark skin be considered inferior? That’s what I think we’ve done.”