There has been talk about it for years — tales of vast seams of gold, platinum and other precious metals just waiting to be seized by those with the nerve.

Some say there’s $700 billion billion of the stuff up for grabs — enough to make everyone on Earth multibillionaires.

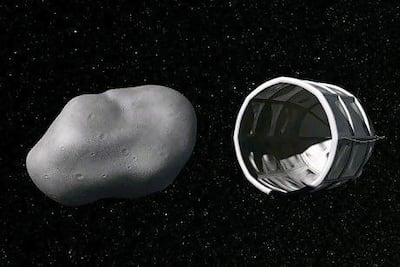

There is just one catch. It lies buried millions of miles away in asteroids, chunks of space debris orbiting between Mars and Jupiter.

But that hasn’t deterred the emerging community of “space miners” — modern-day counterparts of the Forty-Niners, who raced to California in 1849 following the discovery of gold there.

They insist the necessary technology either already exists or is well within reach, and the only real barrier is vision — and money.

Now governments are taking space mining seriously. As reported in The National, the UAE will soon join the US and Luxembourg in having legislation allowing would-be prospectors to keep whatever they find.

Certainly there is good reason for thinking the gold and other riches really are out there. Once dismissed by astronomers as “vermin of the skies", asteroids are now known to be remnants from the birth of the solar system. By bouncing radio waves off them and analysing their light, astronomers have been able to probe their chemical make-up.

Some asteroids appear to be rich in metals like iron and nickel, and may contain precious metals in concentrations 10 to 20 times higher than in Earth-bound mines. As a bonus, the weak gravity of asteroids means the heavy metals haven’t sunk deep below the surface.

According to Planetary Resources, an early US-based entrant in the space mining business, a single half-kilometre wide platinum-rich asteroid can contain more of this class of precious metals than has ever been mined on Earth.

Formed in 2012, Planetary Resources raised $50 million from investors by 2016, among them movie director James Cameron. The following year Deep Space Industries entered the fray, backed by investors and some US government contracts.

While their engineers began developing the technology, governments are doing their bit to boost confidence in space mining.

In the 1960s, the international Outer Space Treaty was drawn up to prevent countries claiming sovereignty to astronomical bodies like the Moon. The US Congress has since passed legislation making clear that US companies have the right to exploit asteroids – removing a concern that could spook investors. Now the UAE has done the same.

In revealing the plans, director general of the Emirates Space Agency Mohammed Al Ahbabi said the legislation is a “law for tomorrow” to anticipate future developments in space mining.

But the signs are it won’t be needed any time soon. For not even the prospect of unimaginable wealth has quelled investor qualms about the viability of space mining. Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries have both quit the field, unable to raise sufficient capital.

A recent analysis in the MIT Technology Review found that the decades-long investment timescales plus the technical demands of space mining have proved a deadly combination.

While conjuring up images of robot diggers and rockets laden with gold zooming back to Earth, the reality is far more demanding.

Simply finding suitable asteroids will require fleets of prospector satellites to confirm the viability of each site.

Nasa will lead the way in August 2022, with the launch of the Psyche mission. This will target the eponymous asteroid which studies suggest is made almost entirely out of metals. Equipped with high-def imaging plus neutron and gamma ray detectors, Psyche will arrive in early 2026 and give the first-ever glimpse of what might be on offer to space miners.

According to some guesstimates, as much as one part per thousand of the asteroid’s mass may be precious metals including gold (a figure which lies behind that $700 billion billion guesstimate of the fortunes to be made).

Actually digging the stuff out is a far bigger challenge, however. Robot miners will not just have to land safely on the often oddly-shaped asteroids, but also manoeuvre across their surface. That is no trivial matter in gravity fields so feeble that a human could literally jump off into space, never to return.

Even so, there is grounds for optimism. In November 2005, the Japanese probe Hayabusa landed on the tiny asteroid Itokawa and attempted to get samples from its surface. Although these failed, some dust ended up in its sample container, and these were successfully returned to earth in 2010.

Yet the biggest challenge to space mining is not technological, but economic.

Propelling loads to and from the Earth is notoriously expensive, which means processing of mined material will have to be done in space – and probably on the Moon. That, in turn, means a processing plant will have to be built on that inhospitable world before the money really starts to flow.

And then there is the single biggest problem facing space miners: the law of supply and demand. They need to find some way of making their efforts pay without flooding the market and triggering a price crash.

A salutary story about getting it wrong dates back to the early 1800s. Miners in Brazil and Uruguay discovered huge deposits of amethyst – at the time a precious gemstone on a par with rubies and emeralds. But in their eagerness to cash in, so much of the mineral was released that the price plunged. Ever since, amethyst has been regarded as just another semi-precious gem.

One way out of this Economics 101 bind is to create extra demand for whatever the miners dig up. It is a business model made famous by the De Beers diamond mining company.

Originally based in South Africa, the company had access to some of the richest diamond fields ever found. To keep the price high, the company tightly controlled production, while boosting demand by marketing diamonds as the ultimate token of love.

Space miners may well succeed in getting the technology to work. The real ingenuity will come in finding ways to charge a premium for what they haul back to earth.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Professor of Science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK