There are startling echoes of Somerset Maugham's 1921 short story "Rain" in the recent death of John Chau. "Rain" is about a proselytising American missionary on the islands of the Pacific. Chau died in an attempt to convert to Christianity a hunter-gatherer tribe on North Sentinel Island, in the Bay of Bengal. Both stories illustrate the tragedy that can result from misplaced western attempts to "civilise" the world and remake it in its own image.

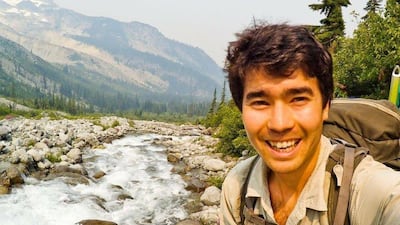

Chau reached North Sentinel on November 16 and is thought to have been killed by tribesmen with bows and arrows shortly after. On November 17, fishermen observed from a distance as the tribe buried the 26-year-old American's body. At the time of writing, it seems highly unlikely that Indian authorities will ever be able to recover Chau's body, or prosecute his killers.

The Sentinelese, who number in the few dozens and are thought to be the world’s last pre-Neolithic tribe, have remained cut off from the outside world for centuries. They have protected status under Indian law and are fatally vulnerable to the most basic modern infections. Accordingly, Indian authorities have largely left the Sentinelese alone for more than 70 years.

So, the chances are that Chau's death will go unpunished and the strange mixture of deep religiosity and daring that drew him towards his death will drop out of the news cycle. But his doomed undertaking bears examination. Was his death a "murder", as we understand the word? Or was it simply an attempt at self-preservation by a community that knows nothing of the world beyond its forested island? What was Chau doing setting foot on North Sentinel Island anyway? Didn't such "civilising' missions end with the colonial era? Why did Chau feel he had the right to break Indian law in order to bring his notion of God's word to the Sentinelese? How should we judge his presumption in endangering a vulnerable, dwindling community by establishing physical contact?

In August, the Indian government loosened some restrictions on visits to North Sentinel and 28 more of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands, in order to foster tourism. However, foreigners journeying to the area still need to complete three mandatory procedures. As an unnamed Indian Home Ministry official told the Indian media, Chau should have done the following: informed the local Foreigners Regional Registration Office, and secured approval from the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, as well as from the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change.

He did none of these things, and was obviously not only on the wrong side of the law but going against science. According to Delhi University anthropology professor PC Joshi, Chau risked not only his own life, but that of the islanders. "They are not immune to anything. A simple thing like flu can kill them," he has told the media.

And yet, Chau was simply trying to do what he thought was right. Before he set out on his tragic venture, he argued against attempted retribution in the event of his death. “Please do not be angry at them or at God if I get killed,” he wrote in a last letter to his parents. They too have gently but implacably pleaded that no one – least of all the fishermen who took Chau to the island – be punished. "He ventured out on his own free will,” the family said. They added that Chau’s “own actions” had led to his death.

That death followed a heartbreaking sequence of all too human misjudgments. It is no comfort – nor any extenuation – that such misjudgments have occurred repeatedly, over hundreds of years. Centuries before Chau, white westerners embarked on missions around the world, believing, as Chau did, that they were God’s instruments. According to reports, Chau himself once said that, in addition to Jesus, he was inspired by the Victorian explorer and missionary David Livingstone.

In the colonial era, white missionaries, explorers and adventurers sought to stamp their imprint on the “other”, deeming local customs sinful and those who practised them savage and in need of salvation. They would have recognised the words Chau wrote in his diary, shortly before he was killed: “Lord, is this island Satan’s last stronghold, where none have heard or even had the chance to hear your name?”

That sense of moral superiority is evident in Maugham’s story about the missionary, Mr Davidson, and his prim wife in the islands to the north of Samoa. They speak of “the depravity of the natives” and the urgent need to deliver them from evil by putting an end to their joyful dancing.

Nearly a century on from the death of Maugham’s fictional missionary, Chau’s tragedy lays bare a lingering attitude – puritanical, prejudiced and patronising – towards non-western peoples. It must stop, for it never ends well.