Fourteen-year-old Sapna Chavan, who lives in an overcrowded slum in Mumbai, has not been to class since March, when schools shut across the country due to the coronavirus pandemic.

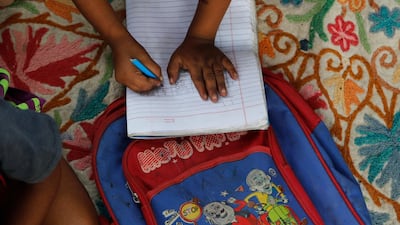

Instead, she sits on the floor of her tiny one-room home using a cheap smartphone provided by a local NGO to attend online classes organised by her government-run school. Her two younger sisters and brother work alongside her in the cramped, dimly lit room while their mother cleans.

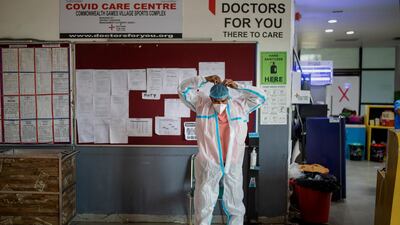

In some states, including Madhya Pradesh and Assam, schools have been partially reopened for older students (grades 9-12) to attend on a voluntary basis, but the majority remain closed. With Covid-19 cases rising sharply across the country, which is the third worst-affected globally with almost six million cases, it could be months before some students go back to class.

As a result, schools in several states, including Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala have started offering online lessons, but for many families unable to afford digital devices or internet access, the pandemic has put education on hold. Now, education experts say that some children may never go back to school, widening the gap between rich and poor and jeopardising the prospects of tens of millions of children trying to pull themselves out of poverty.

“There's always been a divide,” says Sunita Gandhi, the founder of Global Classroom Private Limited and the Global Education & Training Institute in India. “Because they can't afford it, they have to go to government schools, which are not working very well in some regions – or it's because of the lack of good quality teachers; there are so many factors that define learning outcome.”

The current situation has only exacerbated these earlier challenges, Dr Gandhi says, as weaker schools and teachers find it more difficult to adapt to running virtual classes. And there is often less support for children from poorer families at home – parents often have less time to help with homework amid the pressure of finding enough work to make ends meet, she explains.

“We see a lot of pitfalls and the divide getting bigger, the longer it takes for the children to get back into schools,” says Ms Gandhi.

There were 364 million people living in poverty in India in 2015 to 2016, approximately 28 per cent of the population, according to a report by the United Nations Development Programme.

Ms Chavan, who has crucial exams coming up next year, says it is hard to learn much these days. Her home does not have Wi-Fi because the family cannot afford it. Her father, a labourer who would normally earn a few dollars a day, has been out of work since March, when India's nationwide lockdown came into effect as the country tried to limit the spread of Covid-19.

“Sometimes the data connection is bad, and I can't hear what the teacher is saying,” she says. “I don't like it at all. I miss going to school with my friends.”

Sapna enjoys school and is eager to do well in her exams next year so she can eventually secure a good job as a lawyer , but now she's worried about falling behind.

At the other end of town in a more affluent neighbourhood is 12-year-old Prisha Shah. Her online classes started in June, when the state of Maharashtra, of which Mumbai is the capital, instructed schools to begin virtual lessons.

In her comfortable home, she uses a laptop to attend online classes that are being conducted by her private school for about five hours each week day. Her parents are pleased that her education has resumed in a structured way after a three-month gap.

“I've seen that the teachers are making a lot of effort,” says her mother Hemali Shah, who is herself a teacher. “Still, I feel actual classes are better because of the personal touch.”

Ms Shah misses her friends and playing sports at school, but notes that virtual school has its advantages. “You can sit comfortably on your bed during virtual school,” she says.

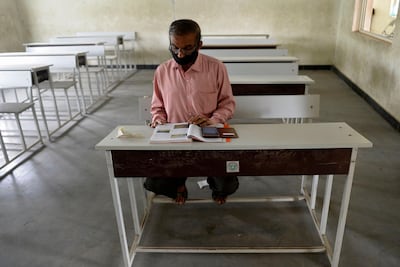

Only a small minority can relate to her experience of education during lockdown in India. In rural areas, the challenges surrounding education are even more complicated because of limited access to the internet and patchy connectivity.

A few schools have found creative ways around this, with some broadcasting their classes over loudspeakers, while outdoor group classes have also been organised in some villages so that pupils can keep a safe distance while they learn.

Some state governments have organised lessons that are broadcast on dedicated channels on television.

“Every single educational institute in India is closed,” says Dhruv Sengar, the chief strategy officer at Lokarpan, a not-for-profit organisation in India. “Virtual classrooms is a reality that exists in the cities. It's not something that is easily accessible to villagers.”

Lokarpan is working with some rural schools in Uttar Pradesh in north India, providing laptops to children, and organising classes with top teachers across the country and abroad, in an effort to help them continue their studies.

But the quality of education is generally weaker in rural India to begin with, Mr Sengar explains, and the pandemic poses further challenges.

A recent survey by India's National Statistics Office reveals that only 15 per cent of kids in rural areas have access to the internet, compared to 42 per cent in urban areas.

Rustom Kerawalla, the chairman of Ampersand Group, a solutions provider for educational institutes, says that the impact of the pandemic has been “very disruptive” in India.

“The entire education system has suddenly had to move into the online space, and definitely we were not ready for it,” he says.

It is challenging in the short term, but in the long term, virtual learning could benefit poorer children too, he says.

“The silver lining is this will be a welcome change that was long overdue. The current pandemic has been a catalyst.”