The late Robert Mugabe, who liberated Zimbabwe from colonial rule, only to hold his country hostage to 37 years of fear and suffering at the highest level, once boasted while campaigning: "I have many degrees in violence. You see this fist; it can smash your face.”

He is regarded by many as the founding father of his country, but he stole and looted from it until his death last Friday in Singapore, at the age of 95. Mugabe remained until the end a hugely polarising figure, having destroyed the country that had once been the jewel of Africa.

The Zimbabwe I knew in the 1990s and early 2000s was a miserable place. Hyperinflation was so bad that to buy a cup of coffee, you practically carried a shopping bag of cash. Foreign journalists, controlled by the powerful Ministry of Information under the mercurial politician Jonathan Moyo, were rarely allowed into the country legally. We had to sneak across the border from South Africa and then work clandestinely, moving from from safe house to safe house to avoid getting thrown in prison.

What I remember most about those days – aside from the intense paranoia, burning farms, torture, abuse of power and the food shortages while people starved, and Mugabe and his wife Grace continued to live in spectacular fashion – were the people I called the "small voices".

During the 2002 elections, they bravely struggled to oust Mugabe from power, taking huge risks and sacrifices, often working undercover. I travelled throughout the country, meeting them in their houses, on street corners, in churches. They were always hidden but always strong.

There was Robert, a student activist for the Movement for Democratic Change, who had been imprisoned, beaten, tortured and violated, working out of a small village near Bulawayo. Mr Moyo had enlisted "war veterans" from the War of Liberation who were basically thugs, briefed to beat up anyone who tried to campaign against Mugabe and his Zanu-PF party and intimidate voters. Student Robert was one of their targets but he persisted, despite the constant surveillance.

There was Maggie, whose house in St Peters, a small village, had been burnt down by Mugabe activists, along with her voter identity card. I met her standing outside the ashes of what had once been her home. What she mourned most was her ID card, her right to vote.

There was Gordon, a journalist who taught me the word "chengwa", meaning change. There was Grace, who tried to enlist other students to help her fight the sexism and machismo that went hand in hand with politics at the time.

Then there was the late Zimbabwean journalist Mark Chavunduka, whom I met in London when we both won Amnesty International awards. He founded and edited the country's independent Sunday newspaper, called the Standard, but died in 2002, in his 30s, after a long illness. He used his short life to wage a battle against Mugabe by "irritating" the government. He was thrown in jail several times and was once tortured for nine days running, suffering waterboarding, beatings and suffocations.

“I don’t know how I got through it,” he told me. “At one point, I begged them to shoot me to end it.”

Yet Mark kept writing and irritating. Along with Robert, Maggie and Grace, he and many others kept speaking out. These are the kind of people who waged a quiet war against Mugabe, using non-violent resistance.

This method of overthrowing governments has fascinated me since I met students of the civic disobedience movement Otpor in the former Yugoslavia, who helped bring down the dictator Slobodan Milosevic in a few weeks in 2000 – something four wars could not manage. They did it using the principles of Gene Sharpe, an American professor who has long advocated non-violent techniques to topple dictators.

The Otpor disciples grew up and turned non-violent change into an industry: they have now reformed as the Centre for Applied Non Violent Actions and Strategies, or Canvas, and go around the world advising would-be revolutionaries on how to effect regime change without people dying.

It’s the Gandhi and Martin Luther King approach – mobilise people, speak out, use quiet tactics that infuriate dictators. But in Zimbabwe, the repression was so strong that the people who remained committed to change had to suffer a great deal in the process.

I remember talking to Shari Eppel, a psychologist who ran a trust for the victims of Mugabe’s torture, who told me that most of her victims would go back to doing their undercover work, even after they were brutalised. “They just want to vote, even after they have been tortured,” she told me.

So when I heard about Mugabe's demise, I did not think of him. I thought of them and the lessons I took with me of how to effect change. Living in America now and watching the Democratic Party – the only hope for change from a polarised world under president Donald Trump – split and faction, I can't help wondering if they should go back to basics. Lessons from Zimbabwe might be a stretch; the country is still not healed, the infrastructure is ruined and the mood in Harare is still disbelief. But Sharpe's principles are available to all.

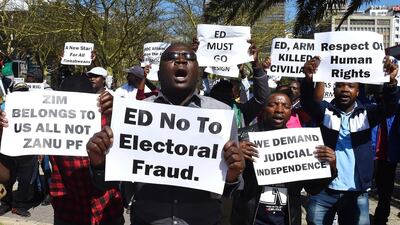

The legacy of those small voices remains. Mugabe led his country to freedom and broke the yoke of white rule. But he became a monster. Today, millions of Zimbabweans are still on the brink of starvation. Fuel prices have increased 500 per cent since January. There are electricity and water cuts. The army and the thugs still attack protesters.

I lost touch with Robert the student. The last I heard from him was when I successfully got out of the country and then received frantic messages from him that Zanu-PF was surrounding the Movement for Democratic Change office in Bulawayo where he was trapped.

“They are outside with combat gear and bazookas,” he shouted. “Please call the cameramen, call photographers! Let the world know this injustice.”

I tried to reach Robert for a long time after that but his phone number no longer worked. I anguished whether he was in jail, or worse.

After a while, I gave up. But I like to think Robert had changed his number or threw away his phone but was still somewhere, still working against injustice, keeping the fight alive.

Janine di Giovanni is a senior fellow at Yale’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs and a 2019 Guggenheim fellow