“I have to solve the online Mini Crossword in The New York Times every night; it is strangely relaxing and gives me a sense of accomplishment before I go to bed,” says Nandita Godbole, 49, a writer who lives in Atlanta in the US.

“For me, it’s about mindfulness and self-care. When I was younger, our family would make a beeline for the afternoon newspaper, and it was a competition between my dad, my aunt and me to see who would solve the crossword first.”

The crossword puzzle was invented in 1913 by journalist Arthur Wynne, who worked at the New York World, as a numbered, diamond-shaped grid that he called Word-Cross. It has since captured the imagination of millions around the world with its black and white grids, and clever clues that are purported to improve memory, problem-solving skills and general knowledge. As Word-Cross grew in popularity, newspapers across the world began to feature their own crosswords.

Puzzle solvers often went to libraries to refer to encyclopaedias or dictionaries to solve difficult clues. The New York Times was one of the last major publications to start publishing a crossword in 1942, to divert the reader’s attention from tragic world events. The puzzles became a source of comfort for many, especially during times of war.

co-founder, Amuse Labs

Several studies, including one conducted in 2017 by King's College London and the University of Exeter Medical School, say that people who play crossword puzzles are more likely to have better brain function as they grow older.

Now, with most people reading their news on mobile phones or tablets, publishers are trying to woo younger readers with digital versions of crossword puzzles and games. However, not many enthusiasts are aware that the puzzles for the digital platforms of several prestigious publications – ranging from The New Yorker and The Hindu to The Guardian and The Washington Post – are made by Amuse Labs, a company that was launched in 2014 in Bengaluru, India.

The idea first came to Sudheendra Hangal (who has a doctorate in computer science) and his wife Jaya Hangal (who was part of the core team that developed Sun Microsystems' Java software platform) when they wanted to build a quiz for children around classical music and using visual clues.

The Indian couple collaborated with a fellow former student of Stanford University, John Temple, to create a similar platform for digital puzzles.

Temple had been managing editor at The Washington Post, and was well aware of the high engagement of online puzzles and games, and their importance in building reader loyalty.

journalist

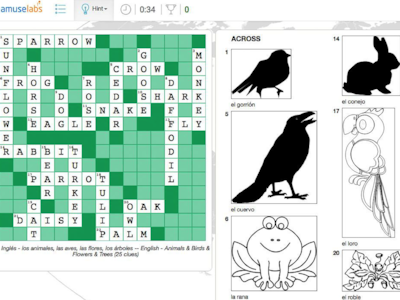

Amuse Labs' PuzzleMe is an HTML5-based platform that publishers can use to create multimedia crosswords, Sudoku grids and word-search puzzles – all in a matter of minutes – that are then embedded on their websites. These can then be played digitally on mobiles and tablets.

The clues can also incorporate multimedia, such as pictures, YouTube videos and audio clips. Media houses aside, PuzzleMe is also used by schools, government agencies, lawyers and doctors.

“The platform offers more than 20 language options, from Urdu to Hebrew, and also collaborative playing where two or more people can solve a puzzle simultaneously,” Jaya tells The National.

The embedded quizzes also have analytics, which show how many readers solved the puzzle, how long they took, where they come from and so on.

“We customise the experience for every publication, so the user experience is different in each case. From the design, font to the colour used, we give [each puzzle] the look and feel of the newspaper, be it The Washington Post or The Hindu,” explains Temple.

The format has its detractors, though. Chandni Doulatramani, a journalist from Bengaluru, says: “I was introduced to crosswords in the printed newspaper when I was about 16 by a friend’s father, and had to wait for the answers until the next day. Now I solve The Guardian’s quick crossword and I can check the answers immediately in the digital format, but that’s no fun.”

It does beg the question whether old-fashioned crosswords are still relevant despite the digital age, given many people prefer the time-honoured way to solve them – on paper, with pen.

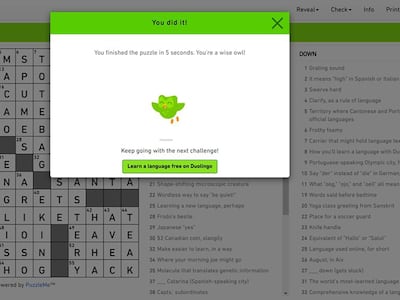

“Digital crosswords and puzzles allow for greater interactivity, where families and friends can play with each other, and it can also teach you more than a print puzzle. There are explanations about the clues and answers, there are cartoons that pop up as you pause, plus many other enjoyable interactive features that make solving a puzzle a richer experience,” says Jaya.

Temple says a crossword puzzle is something of a treat in any format.

“I used to get more calls if there was an error in the clues or solution of a crossword puzzle than an error in a story,” he says. “Comic strips and puzzles add cheer to a newspaper. A person may spend just five minutes reading the news, but spend an hour or two solving the puzzle, and it’s something that readers look forward to, especially in a world of depressing headlines.”

However, the way he looks at it is that PuzzleMe is “contributing to a renaissance of the old-fashioned puzzle in the digital world, which is the direction the world is moving”.