The dusty chairs at the Amman train station are empty. There are no departures today. Vintage carriages line up on the tracks waiting for passengers, but the last train to Syria departed a decade ago. "When I travelled to Syria by train, I was just a child – I was this tall," says Jordanian Maan Nasa while placing his hand at the level of his waist. "Around that time, my grandfather worked for the rail company."

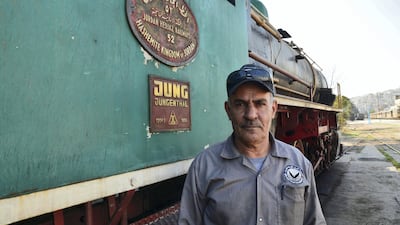

Nasa, who is now 63 years old, has always lived close to the railway that crosses Amman from north to south. An experienced blacksmith, for the past 10 years he has been working at Jordan Hejaz Railway Corporation, renovating old trains for tourism.

He picks up a photo album and starts to thumb through images of the restoration work he has done with his team. Maybe among those rusty trains he has helped restore is the carriage he rode to Deraa, in the south of Syria, so many decades ago, he muses as he flicks.

One hundred years ago, travellers would fill the Jordanian capital's station, waiting for the trains to take them to Damascus, Madinah or Haifa along the Hejaz rail line, built under Ottoman rule. The railway was constructed when Sultan Abdul Hamid II reigned, to transport pilgrims to Makkah and to strengthen Ottoman control of distant provinces in the Middle East. "The railway had a profound impact on the region," says Aylin Orbasli, a specialist in conservation and heritage management and reader in Architectural Regeneration at Oxford Brookes University. "It was an amazing feat."

The journey between Damascus and Madinah used to take 40 days by camel caravans. The trip was reduced to about 72 hours when the railway was inaugurated in 1908. But the line never reached Makkah, and plans to extend it further were interrupted by the First World War. Arab guerrillas rebelling against Ottoman power sabotaged the railway, which was used to transport troops and weaponry. Due to the damage caused during the war, the southern sections of the rail – in what is today Saudi Arabia – were abandoned.

Connections were also lost when new borders were drawn by the colonial powers that divided the Middle East between them after the war. With the establishment of Israel in 1948, the line that linked Haifa to southern Syria shut down. Syria’s railway system was also damaged in the ongoing war, cutting off the last cross-border rail tie of the historic Hejaz line. As conflicts proliferated and borders hardened, a time when it was possible to travel by train across the region seems impossible to imagine today.

"Even if it's not possible to revive the railway as a physical link, if it's recognised as a World Heritage Site it could be unified in an intangible way," says Orbasli. The Hejaz railway is part of Saudi Arabia's Tentative List of World Heritage Sites, submitted to Unesco in 2015. Indeed, recognising the railway's heritage value might be a way to revive it, but there are other ongoing projects trying to restore life to the abandoned tracks, too.

For example, Jordanian architect Hanna Salameh wants to turn the rail line green. Earlier this year, he announced his vision to plant trees along the railway and to substitute the train with a tram in a video that proved popular on YouTube.

Salameh, who has been ranked among the Middle East’s most influential architects, wants to redevelop the neglected railway by turning its surrounding area into a public park. His proposal aims to make use of the existing infrastructure to create green spaces and improve accessibility in Amman.

It's not all defunct, though. Touristic trains sometimes still carry passengers to the station of Jizah, south of Amman. But Salameh thinks the steam locomotives, which run through residential neighbourhoods, are polluting and a safety hazard. "We wanted to keep the train, we were just concerned about safety," Salameh explains. "The track crosses very sensitive neighbourhoods where the curves are tight and there are kids playing next to it. But if we have a tram, it will be much safer."

Building a park and a tram system would be a great way of preserving Hejaz railway's history and location, says Orbasli. "Anything that supports easier accessibility and infrastructure would add value to the railway," she says.

After all, improving mobility is a major concern in Amman, where only an estimated 5 per cent of the city's residents use public transport. Because of the high number of private cars, traffic congestion and pollution are big problems. Transport consultant Hazem Zureiqat agrees with Orbasli. "I think it's a great idea because it tackles three challenges that we face in Amman: the lack of safe pedestrian passages, the lack of public spaces and the lack of public transport and mass transit."

In 2016, Zureiqat helped launch Amman’s first public transport map, created by Ma’an Nasel, a public transport advocacy group he founded with other civil society activists. “We need a public transport system that serves a large number of people and that matches people’s needs,” he says.

Answering residents’ needs is one of Salameh’s goals. If his project goes ahead, he plans to spend a year consulting with the people who live close to the railway and getting them involved. “We can’t assume to know what their needs are, because we don’t live in those areas,” he says. “By designing with the community we are going to end up with a superior design. But the most important thing is that they would feel part of the project.”

Salameh emphasises that his Hejaz Railway Park would not just improve transport connections by running a tram on the line that crosses Amman from north to south, but it would also help residents reconnect with their city, where the lack of public space makes many feel detached. “Our country has been suffering from the lack of public space,” he explains. “We have a lack of connection to our own city. We don’t feel that it’s ours.”

While Zureiqat and Orbasli both point out that more detailed feasibility and sustainability studies would need to be undertaken before it goes ahead, they support the park and tram project, saying it would be an asset to the railway and to the city. Others, however, are not so optimistic.

“It’s a wonderful project, but it would take a lot of money to finance it,” says Nidal Alassaf, deputy director-general at the Jordan Hejaz Railway Corporation, an entity of Jordan’s Ministry of Transportation. To counter this, Salameh says he has developed a plan to fund the project without depending on taxes, as Jordan is currently heavily indebted. He wants to develop a “live zone” that can support itself and generate energy and income. “The challenge in this park is that it has to be self-funding and community sustaining,” he admits. “So it needs to not only cover its own expenses, but [also] to be income-generating for the people living around it.” He says this would be possible if the park had solar panels that could produce energy, and if the space was rented to businesses to generate revenue.

The young architect is also quick to emphasise that having a tram running on the historic track doesn’t mean giving up entirely on a railway system. For safety reasons, a high-speed train should be diverted out of the city, but a switch terminal could connect it to the tram. “We need a regional rail network,” he says. “In our region, the borders are very harsh. It’s a very small region, but there is so much conflict within its borders. It’s bigger than the physical borders. It’s the emotional borders as well.”

Zureiqat says that, regardless of political disputes, trains symbolise a longing for fluidity and mobility. “It’s something that a lot of people dream of when they think about open borders in our region, or even when they’re stuck in traffic and unable to travel to other cities.” For now, the chairs at the Amman train station will remain empty, waiting for travellers and better days to come.