When I announced a visit to Saudi Arabia, my friends' reactions ranged from surprise to consternation. Why, they wondered, and what was there? Others were less receptive. The consensus was that visiting would be an academic exercise at best and, for western women wrapped in the obligatory abayas, a chore. The Saudi enigma seemed couched in severe and not particularly positive terms even, or perhaps particularly, by those who had never visited. Yet for people who are curious about a place that seems at once familiar (we can all conjure a mental picture, and most can place it on a map) and yet enigmatic (just what is there?) - or simply seek a destination few people have visited - Saudi Arabia is just the ticket. Apart from the annual Haj that draws millions of pilgrims, few outsiders are doing any sightseeing in Saudi. Until 2006, the sheer difficulty in simply procuring a tourist visa was enough to discourage tourism. While western expatriate residents can tour at leisure, tourists are thin on the ground. Fewer than 5,000 Europeans visited in 2008, with Germans forming the vanguard. However, the visa regime has softened, making the kingdom more accessible. Although visitors still need to be on an organised tour, the minimum group size is now four and the minimum age for unaccompanied women has dropped from 40 to 30 (below which they need to be accompanied by a husband or male relative). I joined a small group including a retired couple, an ex-banker, an oil company geologist and an American art collector. Most were over 50 and extraordinarily well travelled, through either work or wanderlust - Congo, Angola, Papua New Guinea and Yemen, for example, had all been ticked. Saudi Arabia was among the last frontiers and their interest was genuine. The women's tailor-made and obligatory abayas - a long, generally black, robe that cancels shape (and arguably femininity and even temptation) - were awaiting them at Riyadh airport where we began our tour. As one quipped, it was the first destination where she'd needed to provide her passport details and vital measurements to get a visa. We men were fine in short-sleeved shirts or T-shirts, and no one had been daft enough to turn up in shorts. The ladies quickly adapted, and almost warmed, to their abayas and none were required to wear a niqab, or veil. They were light, comfortable and effectively removed the agonising over what to wear underneath each day. Riyadh is capital in name but not, it would seem, of culture and commerce - that honour goes to Jeddah on the Red Sea coast. It is a modern city of boulevards and expressways and rather too much utilitarian concrete offset by a handful of architectural masterpieces. Yet at its heart stands Masmak fortress, whose mud-brick walls with rounded bastions, loopholes and crenellations evoke another, almost medieval, age. It is also where modern Saudi Arabia was born.

In 1902, a young Abdul Aziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud seized Masmak from his family's main rivals, the Al Rashids. You can still see his spearhead embedded in its wooden gate. Today it's an acute and virtually official symbol of his pivotal rise, an episode dramatically recreated in a short film that plays in Masmak's museum. Amid its halls and rooms with displays of photographs, weapons and armour is a plaque commemorating Saudi Arabia's National Day that refers to the country's "destiny which, first and foremost, brings honour to Allah and then to the creator of that unity King Abdul Aziz..."

His status as father of the nation - its unity was formalised only in 1932 - is reinforced in every, mostly excellent, regional museum up and down the country. Riyadh's vast National Museum is by far the best and probably one of the finest in the Middle East. Focusing on clarity and quality over sheer quantity, it covers history, archaeology, geology and Islam. Abdul Aziz has a separate wing comprising mainly old photographs, his Rolls Royces and some personal items such as robes and his doctor's medical chest. The display even includes two of his brick-sized bath soaps. We moved on to Dir'aiyah, an ancient mud-brick city on the fringes of Riyadh, which was the Al Sauds' original power base. Here, explained Saad, our Jeddah-based guide who was to accompany us for the duration of our trip, in 1744, a scholar called Mohammed ibn Abd al Wahhab befriended (and eventually married his daughter into) the Al Saud family. The country already subscribed to the Hanbali school of jurisprudence, the most conservative of the four schools in the Sunni tradition. Abd al Wahhab's influence coupled with Al Saud patronage steered the region into a yet more puritanical form of Islamic interpretation, and became a rallying doctrine for many Arabian tribes. It is this that distinguishes modern-day Saudi from other Muslim countries, including most its GCC neighbours.

Armed now with a semblance of basic history, the Saudi enigma had some context. We were keen to wander Dir'aiyah's atmospheric maze of lanes but they were closed for restoration work so we could only gaze from the fences. Clearly, more tourists are expected soon. Most of our tour was to encompass the country's northern half and we flew to the city of Al Jouf, which lies on the main road routes towards Jordan and Iraq. At nearby Domat Al Jandal, a once vital oasis town with a recorded history starting in the sixth century BC, stands Qasr Marid. A local guide, Saleh, took over from Saad, saying the small picturesque castle was reputedly built by a grandson of Ibrahim and besieged by Palmyra's (now in Syria) Queen Zenobia. "It may also have been visited by the Prophet Mohammed, peace and blessings be upon him," he added. From its ramparts, we gazed over the crumbling old town with its jumble of dissolving walls, collapsed homes and blocked streets. Dominating the view was the Umar Mosque and its distinctive tapering minaret with a tiny staircase accessing a series of little doorways. It is among the oldest mosques in Saudi Arabia, though, strangely, Saleh initially made little of it; were it not for our enthusiasm it might have been ignored altogether. A six-lane motorway crosses Al Nafud, Saudi's second largest desert after the Empty Quarter, south from Al Jouf to Hail. A police escort - always a feature of our journeys - drove behind and stopped midway when their colleagues from Hail took over. Saad caught our quizzical looks. "For your security ... some crazy drivers in Arabia," he beamed, though we really only believed the first part.

Vast expanses of undulating pale orange sand dotted with sprigs of acacia slid past for hours until patchy green fields and quad-bike stalls heralded town. Opposite our hotel stood a McDonald's (often referred to as "Eighty-eight" because its stylised "M" logo resembles the Arabic characters for 88). Off to the right stood a KFC and Pizza Hut, neither of which were particularly busy. Hail was the stronghold of the Al Sauds' once great rivals, the Al Rashids, and it wasn't until the 1930s that Abdul Aziz built his mighty Al Qashalah barracks in the centre while tactfully opting not to interfere with Al Rashidi properties. It's an imposing square building of 10-metre-high walls with machicolations and holes to drop burning oil. We walked up to 'Airif, a compact Al Rashidi fort which tops a ridge at the edge of town and has recently been thoroughly restored. Our first real experience of Saudi markets came at Hail's souqs. In one small section, women sold bundles of dried hibiscus and mint and carefully adjusted their abayas and niqabs in the face of our curious yet hopefully polite gaze. While none would be photographed (and why should they?), they were friendly enough and seemed to enjoy a bit of banter with Saad and our escorts.

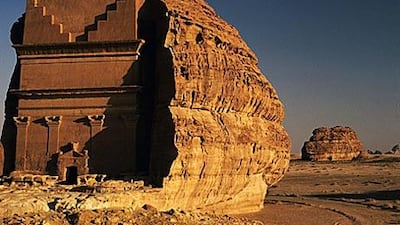

Later I wandered off alone to another covered parade of shops to find Bangladeshi shopkeepers serving the ladies of Hail. They were assessing jewellery and clothes and rummaging through utensils and plastic toys. It was busy, earthy and authentic. There were a few beggars, too: women with infants who, because they were dressed in ubiquitous black, looked no different to anyone else except for their outstretched black-gloved hands meekly awaiting coins. Oil-rich Saudi was proving a little grittier than we expected. Beyond the capital, its prosperity and gloss seemed more diluted. The roads were good but many were new or only recently widened. Moreover they were used by a surprising number of old and tatty cars - far fewer prestige marques than, say, Abu Dhabi or Dubai. Many areas had a generalised, almost reassuring scruffiness to them, such as incomplete pavements and walls. Shopping seemed to revolve around basics, not luxuries - though it's the country's first attempt at tourism and the lack of garish or vulgar desert fantasy there was refreshing. We headed 400km west on the main motorway towards Al Ula through mostly featureless desert steppe, pausing around lunchtime at Taima (or Tayma). For millennia, it was a vast and celebrated oasis that prospered from the caravan trade in frankincense and spices. There is a famous well here, the Bi'r Al Haddaj - reputedly the country's largest - whose 60 draw-wheel fames and channels placed around its rim would have been worked by camels to water an intricate complex of gardens. Later, on the edge of town, we stood on the faint remnants of what was its 14km-long perimeter wall, with potsherds still scattered here and there. One evening Georgios Papaioannou, our guest lecturer and regional expert, briefly outlined the Islamic notion of Jahiliyyah, a reference to the pre-Islamic era that is usually translated as "period of ignorance". As the very foundations and pillars of the faith reside in Saudi Arabia, its culture seems more sensitised to this concept. Perhaps, he ventured, this partly explained why archaeology had not developed here as much as in other areas of the Middle East. There might not be buried treasure-troves, but there's plenty of interest that has barely been excavated, such as the ancient city of Dedan by Al Ula, or Al Ukhdud - reputedly the site of the sixth-century "Massacre of the Trench" - at Najran in the far south. Yet at Madain Saleh near Al Ula, even the Saudis realise they have an archaeological site too imposing to ignore - their very own Petra. Our final approach to Al Ula weaved through weirdly eroded sandstone hills and clusters of boulders before descending into a beautiful palm-choked valley enclosed by rugged ridges. Next morning we strolled through old Al Ula's abandoned and now crumbling mud-plastered houses and labyrinthine lanes overlooked by a small fortress. It was a compelling prelude to Madain Saleh, where nearly a hundred rock-cut facades of tombs pierce the cliffs and spectacular island-like stacks of rock erupt on the desert fringes. This was the Nabataeans' second city of Hegra (now better known by its contemporary name), but, unlike Jordan's Petra, it sees just a trickle of visitors. Accompanied merely by a breeze, we were largely free to wander among these two-millennia-old necropolises amid the echoes of ancient Nabataean caravans transporting frankincense and myrrh from Yemen to Damascus. Many facades have inscriptions, such as "Kamkam's Curse" in tomb 39, where three gods were invoked five times over against any who interfered with it. In its eerie emptiness, you hope the curse has already worked its course.

You can also clamber up to some of the facades' hillocks and bluffs where piles of stones suggest sporadic Roman occupation by small garrisons in watchtowers. The views across the site are terrific. We ended our visit walking through a sheer-sided cleft to climb a hill and watch the sand pinken as the sun dipped behind a bank of stark hills. Few of us doubted Madain Saleh was the trip's highlight. Finally, we made for Saad's hometown of Jeddah. It's a city long used to visitors, especially traders and pilgrims, and it is rightly considered Saudi's most liberal locale. What many conservative Riyadhites regard as decadent here is commonplace through most of the Middle East. At a popular corniche restaurant, there were glamorous, unaccompanied women, with niqabs relegated to headscarves, who smoked shisha and chatted together contentedly. Ultimately, of course, our group's female travellers were glad to cast off their abayas - but not even Jeddah is so permissive. It may not be the easiest of destinations for those of a western mindset, but the tour had cut a fascinating course through its highlights. More than most countries, we were compelled to see it on its own terms. Throughout, Saad frequently alluded to a changing Saudi Arabia. How, we often wondered. "Well, you're here now," he began. travel@thenational.ae