On June 23, 2016, the British voting public stunned most forecasters by choosing to begin the process of exiting the European Union, the world's biggest trading bloc and one the UK has been part of for more than four decades.

In the two weeks before the referendum the British pound surged, partly on optimism of a "No" vote, to a healthy 1.44 to the dollar. But as it became clear the referendum had gone the other way, so sterling's precipitous fall began. Seven days later it had slumped to 1.37 and over the next four months it slid further, briefly dipping under 1.20, before starting to climb back, albeit unsteadily, to a respectable 1.42 on April 13 this year.

Since then, however, the malaise has set in once again and the pound closed at 1.2759 on Friday amid a dollar bull run that has been compounded in the UK’s case by the uncertainty surrounding the country’s official divorce from the EU next March. It was slightly lower at around 3pm UAE time on Monday.

A 25 basis points rise by the Bank of England in interest rates to 0.75 per cent last Thursday failed to halt the slide, in part because economic growth has been weak and participants see fewer rate rises in the pipeline than previously predicted.

The central bank governor Mark Carney's openly expressed view that higher rates will provide the institution more fire power by creating room to cut them back if Brexit goes wrong has also had a dampening effect, according to HSBC's global head of fixed income, Stephen Major, who likened the move to an old English nursery rhyme, The Grand Old Duke of York, about a fictitious UK royal who marched his army up a hill only to march them down again.

"It is the sort of 'Duke of York' policy - you go up so you can go back down again," he told Bloomberg TV last week. “It does sound a bit silly.”

Two years on from the Brexit vote, the pound is still feeling the effect of the uncertainty the referendum has created in British politics as Theresa May’s government appears no closer to reaching a beneficial trade deal with the EU.

Sterling is now at an 11-month low. Comments made last week by Mr Carney that the possibility of a no-deal Brexit is "uncomfortably high" and will lead to higher prices were compounded by Trade Secretary Liam Fox telling the Sunday Times newspaper that "intransigence" by EU officials "is pushing us towards no deal". He put the chance of Britain crashing out without a deal at 60 per cent.

The resulting dip in the pound demonstrated how vulnerable it is to Britain’s tumultuous political arena.

It was all so different in April. A rise in sterling had confounded those who had taken bearish positions on the currency and were fearful their bets were going horribly wrong. “I'll tell you, when it was at 1.43 I was sweating ... I was under massive pressure,” David Bloom, HSBC's strategist said recently. “It was going to be a soft Brexit and the Bank of England was going to raise rates and everything was looking more relaxed.”

Five months on and today analysts across the board predict the currency will continue to be unstable as long as investors believe a cliff-edge Brexit scenario is still a real prospect, ie crashing out of the bloc without any deal.

"As long as the market perceives there is still a chance of no deal then sterling is going to be very vulnerable," Jane Foley, head of FX strategy at Rabobank, tells The National.

Despite there being just seven months to go until Britain officially departs the EU, the two sides remain at loggerheads over what type of relationship they will have post-March 29, 2019.

At home, Mrs May’s position as prime minister is fragile, having suffered two high-profile cabinet resignations in July from Brexiteers opposed to her plans for closer economic ties with the bloc.

"The government is struggling to get a coherent view out into the world about how Brexit is going to play out," Russell Jones, partner at London-based macro consultancy, Llewellyn Consulting, tells The National.

“Recent comments from Mark Carney and also Liam Fox warned of a significant risk of a deal not being done. The feeling is that this would be pretty damaging to the UK economy and therefore people have marked down sterling as a result of that.”

The BOE raised its interest rates to 0.75 per cent a few days before sterling’s latest tumble but that hike was a long time coming, almost a decade after the bank's emergency cut to 0.5 per cent following the global recession. Interest rates in the US have been rising much quicker, a sign of economic recovery, which has adversely affected the pound for some time.

_______________

Read more:

UK central bank: no-deal Brexit risk 'uncomfortably high'

Pound stuck in doldrums on Brexit as dollar strengthens

_______________

“Ordinarily an interest rate increase is conducive with a stronger currency because it becomes more advantageous to put money into a currency that’s yielding a little bit extra,” says Ms Foley. “But we’ve seen sterling flip since last Thursday through political uncertainty.”

In the past a weak currency has made foreign investment in British real estate a more attractive prospect. However, investors are more likely to sit on the sidelines fearing a further slump in the pound, according to Laith Khalaf, senior analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown.

"While there are investment opportunities, overseas investors are loathed to take advantage of them because of the political risk," Mr Khalaf tells The National.

“Lloyds Bank is a good example of this as it is plugged into the UK economy through the mortgages that it sells and all the loans that it makes. It has been performing pretty well over the past couple of years for business but its share price has hardly moved.

"That suggests a reluctance on the part of investors generally to back the company even though to all intents and purposes it is on the up.”

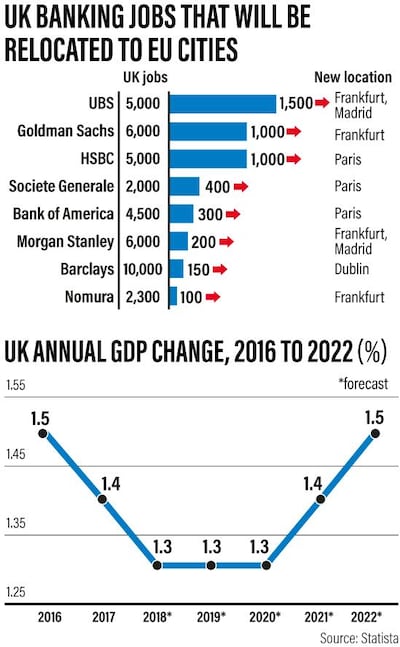

It's not only investors who are concerned. A number of major banks including HSBC, Goldman Sachs and Bank of America have already decided that, because of Brexit, they will move some operations and jobs outside the City of London financial hub, with Frankfurt the primary beneficiary so far.

In addition, economic forecasts reveal most believe the country will not post GDP growth until at least 2021. The Office for Budget Responsibility in March revised growth down for 2021 and 2022, from 1.5 to 1.4 per cent and 1.6 to 1.5 per cent, respectively.