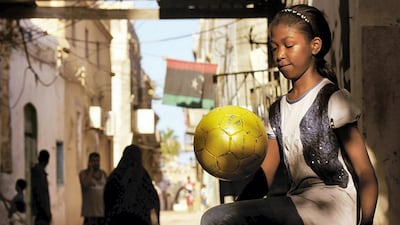

Before 2010 Naziha Arebi had never set foot in Libya – she grew up in the seaside town of Hastings, England. But from 2011, the director spent five turbulent years filming in her father’s birthplace after the violent removal of Muammar Qaddafi that year, and she has made one of the most extraordinary documentaries, covering about football, feminism and revolution in the African country.

Freedom Fields follows three friends, Nama, Halima and Fadwa, who met on the pitch, and tells their story in three distinct parts. The first section takes place one year after the revolution, in 2012, a time of great hope that change would bring democracy and gender equality to the country. It then jumps to 2014, where the overriding feeling is one of loss and confusion as ISIS takes a stronghold. Finally, it moves to 2016, when resilience has become key and sadness at the failure of the revolution turns into a desire to continue the struggle in any way possible.

The documentary uses a quote from Audre Lorde from her 1984 collection of essays and speeches Sister Outsider to convey the sense of change and urgency that defined the spirit of the beginning of the shoot: "Sometimes we are blessed with being able to choose the time, and the arena, and the manner of our revolution, but more usually we must do battle where we are standing."

Arebi went to Libya for the first time with her father after the passing of the “Deal in the Desert”, when Tony Blair and Colonel Qaddafi agreed to a trial of the Lockerbie plane bombing suspects on neutral ground in return for lifting the crippling decade-long sanctions.

Being in Libya was a revelation for Arebi. “I was hyper-Anglicised in many ways because my dad was of the generation that wanted to fit in – ‘we are British’, and all that stuff,” she recalls. “But he was also very Libyan and I was also very Libyan, which I realised when I got there. My family and everyone talks over each other, and are very tactile. And I’m very much like that.”

Meeting the Libyan women's football team

The next time she went to Libya, the revolution was in progress. Women played a key role in initiating the first protests, lobbying, smuggling arms and cooking on the front lines. They were elected key decision-makers after the national elections and there was a sense of optimism. It was hearing about this solidarity, spirit and hope that inspired Arebi to stay in the country.

It was around this time that she found out about the Libyan women’s football team, from a forum on a website based in Britain. “I first heard about this group in London. When I told them I was in Libya they said, ‘What about the Libyan women’s football team that no one has ever met?’ That sounded interesting, so I wanted to find them.”

The football squad had been in existence for almost a decade without managing to play a single competitive match. In 2012, the ladies received the good news that the Libyan Football Federation would allow them to play in a tournament against other Arab nations in Germany. “They had to battle for a very long time and it was these new circumstances that led them to think things might be different after the revolution,” says Arebi. “But they were naive, like I was, that things would change.

“There was a lot of banter and it was like hanging out with friends, which again sounds naive and idealistic,” she continues. “They were the best years of my life, 2011 and 2012. You were in Libya and all these writers, poets, filmmakers, people had fallen out of the woodwork and suddenly we were making things and collaborating. It was a really beautiful bubble.”

Unfortunately for Arebi and the squad, there were plenty of people eager to burst that bubble. Opposition was set in motion with some of the population angry that the girls would be exposing their legs while playing sport in public, worried about a domino effect and the societal change this could lead to. The protests were especially vehement online. The great strength of the documentary is that Arebi doesn’t polarise the arguments. Rather than creating a girls against society polemic in a battle against the community and religion, Arebi shows how the girls try to balance their own religious beliefs, love of football and respect for the norms of public life.

Director Naziha Arebi:

She says of the nuanced approach: “The problem is a cultural one, not a religious one, and that was important for me to convey. The girls in the team are not these exotic Muslim girls trying to carve spaces for themselves with these identities, and they are not defined by their religion. They are defined by their football.

“I didn’t want to show a simplistic representation that can be polarising. It’s far more complex. The girls’ responses are more complex, and I really can’t stand the generational sensationalising of these sorts of stories, as it just biases the narrative.”

One of the toughest days of filming was the day the girls received the news that they could not play in the tournament. “That was a hard day because on one hand you understand the pressure that the federation is under, and on the other there is the frustration of the girls, but I was also frustrated, fired up and wanting to participate and speak, but I couldn’t because I was holding a camera making a documentary.”

There is a two-year jump in the film, but in reality, Arebi kept shooting. Some of the footage will appear in another documentary, After the Revolution, which she describes as "more tragic", and which deals with issues away from the team. In Freedom Fields, the group dispersed as the civil war raged, with the action concentrating on the stories of Nama, Halima and Fadwa.

________________________

Read more:

'Beautiful Days' portrays North Korean defector's past and hope

Dubai's first fully fledged arthouse cinema is now open

First official picture of Salman Khan on 'Bharat' Abu Dhabi set released

________________________

“There were 30 girls initially, and these three girls kind of chose themselves,” explains Arebi. “Fadwa is the more contemplative one and a thinker. Halima is hopeful and gorgeous and from a different demographic to Fadwa. Nama is stomped on at every single level but doesn’t care. They really complement each other well. It’s not one reaction or the other, it’s far more complicated.”

This section is tinged with sadness and loss. There is another two-year gap to when the girls are trying to make sense of what has happened, and also demonstrate their profoundly deep love of football. “We had hope together, lost hope together, and regained it,” says Arebi. “I think the trajectory of having hope and losing it, and struggling to regain it is definitely representative of something a lot of us felt. What I learnt making this film is that we have far more reserves of resilience than I thought.”

Freedom Fields plays at the London Film Festival on October 11 and 12