It’s the James Bond screenplay that nearly derailed the franchise. On display at Peter Harrington Rare Books at the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair is the original Thunderball screenplay, annotated by Bond creator Ian Fleming.

The drama on the page was mirrored in real life, with the script becoming key evidence in a 1963 plagiarism trial that left a mark on Fleming's career and reputation.

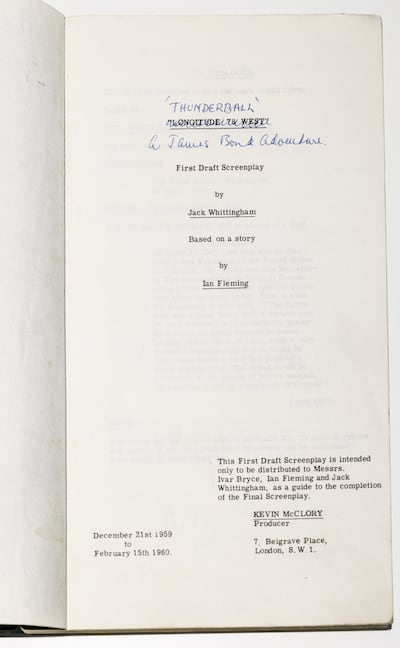

Pom Harrington, who runs the rare book firm founded by his father, calls the document the trial’s “smoking gun”. With title pages outlining a two-year draft process beginning on December 21, 1959, lawyers for co-writers Jack Whittingham and Kevin McClory were able to prove that Fleming’s 1961 novel – also titled Thunderball – was based on their original screenplay. It remains the only Bond novel adapted from another source and the screenplay is on sale at the book fair for £250,000.

“What we have here in Abu Dhabi is the first draft written by Whittingham – so this is essentially the first screenplay,” Harrington tells The National. “What this proves beyond any doubt is the concept. This is the first draft. It shows that this draft was created by someone else, sent to Fleming, and he absolutely acknowledged that – because his writing’s all over it.”

With Fleming’s first six Bond novels – beginning with 1953’s Casino Royale and including From Russia with Love and 1958’s Dr No – gaining global popularity, the idea of a film adaptation was floated by producer and friend Ivar Bryce. British screenwriter Whittingham and Irish filmmaker McClory were enlisted to develop the story for the screen, while Fleming contributed story notes. When the process stalled after two years of correspondence between the trio, Fleming – then releasing a Bond novel annually – used the screenplay as the basis for his next book.

Thunderball was published in 1961 without crediting either collaborator. That decision triggered the plagiarism lawsuit, which reached London’s High Court in 1963 before being settled out of court, with McClory awarded the film rights to the screenplay.

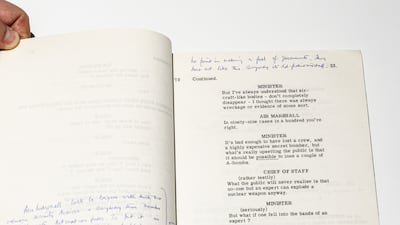

Harrington says handwritten annotations by Fleming on the early draft hint at creative clashes with Whittingham and McClory that would later hamper the project. These notes, written in blue ink, were often staccato.

A blunt line appears on page 22, in a scene where a government minister discusses with military personnel the threat posed by a missing atomic bomb. Fleming criticises the writing as overly simplistic in characterisation and tone. “There is no point making a fool out of the government. They don’t act this way. This is old-fashioned stuff,” he wrote in the margins. Later, responding to a line about a missing plane, he remarked: “Aircraft bodies don’t disappear – they make wreckage.”

“You can almost hear Fleming sighing through the notations,” Harrington says. “He wanted the tone to be sharper, more credible and drawn from his own wartime experience in intelligence. It also makes you think Fleming wasn’t very collaborative, he just wanted to do his own thing.

“The screenplay writing process would start, stop and eventually stall. At this point, Fleming was committed to writing a novel every year and apparently he was running out of ideas. So he went off and wrote his next book, and essentially based it on this script.”

The resulting case took a toll on Fleming, Harrington says, noting that later biographies describe how the trial – which saw Fleming undergo intense cross-examination – affected his health. The writer suffered a heart attack during the proceedings. A second heart attack killed him in 1964 at the age of 56, less than a year after the case concluded.

As for why Fleming vigorously defended himself despite what appeared to be a weak case, Harrington attributes it to the reputational hit an adverse finding would have had on his career and standing. “He moved in high society. His reputation mattered,” Harrington says. “He came from a very wealthy family. Fleming Bank was founded by his grandfather and was enormous. Most of his money actually came from the family, not from writing.”

Harrington said the screenplay came from a law firm involved in the case that had kept the evidence in storage. The firm sent it to McClory’s family estate, which then sold it to the bookshop.

Despite the hefty price, Harrington is confident the Thunderball typescript will find a buyer.

“About a third of what we sell never even reaches the market,” he says. “We get it in, we offer it out. We know who wants to buy it. We know their collection better than they do. If we’re doing our job properly, we’ll say: ‘This fits into your collection,’ even if they haven’t thought of it yet.”

Abu Dhabi International Book Fair is running at the Abu Dhabi National Exhibition Centre until May 5