Each year, hundreds of thousands of new books appear in English, brought out by publishing houses and printers across the world. Yet the pool of literature that's translated into English is relatively small. Within that pool is another, even smaller category: translated works that were originally written by women.

Five years ago, book blogger Meytal Radzinski decided to try to amend this imbalance and in August 2014, she launched Women in Translation Month, to refocus attention on women's writing from across the world. The initiative was necessary when you consider that in 2016, the University of Rochester's Three Percent blog found that only about 30 per cent of new books translated into English were written by women. But Radzinski says the imbalance is not only in the numbers. The translated literature that is promoted and canonised is written almost entirely by men.

Historically, international literary prizes have gone to men. When Svetlana Alexievich won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015, she became the 14th woman to win a prize that has been handed out annually since 1901. Only six women have won the biennial Neustadt Prize, a major global literary award that began in 1970.

A look at lists of recommended fiction often shows an even more lopsided picture, with those focusing on Egyptian fiction, for instance, regularly giving nods to titles such as Alaa Al Aswany's The Yacoubian Building (2002) and Naguib Mahfouz's Cairo Trilogy, books that were first published in the 1950s. Scarcely any women's books are ever mentioned and, when they are, it's more likely to be Agatha Christie's Death on the Nile (1937) than a book written by an Egyptian woman.

Radzinski says the idea behind Women in Translation Month – supported online with the hashtag #WITMonth – is not simply to call for more books by women to be translated. It's also an opportunity to talk about books by women that are already available.

Although the #WITMonth movement started small, it has boomed in the past two years. "In 2014, I naively tried to email some of my favourite bookstores to get them to do #WITMonth displays. I got no responses," Radzinski tweeted earlier this month. "Today, several of these stores have displays."

Publishers and book activists are also marking the month, with Deep Vellum Press, Soft Skull Press and English PEN all using Twitter to give away bundles of translated books by women.

This year could mark a turning point in the issue, and particularly for the translation of work by Arab women. After Jokha Alharthi's Celestial Bodies (2010), translated into English by Marilyn Booth, won this year's Man Booker International Prize, publishers began to look more actively for work written by women in Arabic. Also this year, Palestinian Sahar Khalifeh became the first woman who writes in Arabic to be named as a finalist for the Neustadt.

At long last, it feels like a new chapter is being written.

Here are some translated works by women to check out:

Passionate literary fiction: Huzama Habayeb’s Velvet, tr. Kay Heikkenen (Hoopoe Fiction)

This novel won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal in 2017 and is a piece of passionate literary fiction that follows Hawwa, a Palestinian woman born in the Baqa’a refugee camp outside Amman. The descriptions of the camp are bursting with sensory detail, echoing the overwhelming experience of living among so many people. But when Hawwa escapes – into sewing for her mentor, Qamar, or into her own imagination – Habayeb allows her writing to breathe. All through Hawwa’s life, she loves and hates as deeply as if she were the first person to experience such emotions.

Evocative, experimental short fictions: Rania Mamoun’s Thirteen Months of Sunrise, tr. Elisabeth Jaquette (Comma Press)

This collection of 10 short stories won a PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant in 2017. The book explores the points of intersection between cultures, languages, states of being, life and death.

The stories include fantastic conversations with animals, a tale told as a film script and a story about seven days of love that begins: “We met up as people do. He didn’t make an impression.” Later, he does.

Picture book: Taghreed Najjar’s My Brother and Me, ill. Maya Fidawi, tr. Michelle Hartman (CrackBoom! Booms)

This sweet picture book came out in Arabic in 2016. It’s a short, charming tale of brotherly love, with illustrations by the immensely talented Maya Fidawi. Aloush is a lot younger than his brother Ramez, whom he admires enormously.

But all of a sudden, things change between them. Worse, Ramez says he’s going to get engaged. The brothers can’t put things back to the way they once were, but they can find a way forward – together.

Speculative fiction: Ibtisam Azem’s Book of Disappearance, tr. Sinan Antoon (Syracuse University Press)

What if every Palestinian living in Israeli territory suddenly disappeared? This book starts with two, intertwined losses – the death of a beloved grandmother and an unexplained mass disappearance of people, not unlike the plot of Tom Perrota's The Leftovers. From here, Azem fleshes out a nuanced array of characters. At the centre of the story are journalist Ariel and his Palestinian neighbour Alaa, the latter of whom continues to have a voice in the novel through a journal he left behind when he disappeared, even as Ariel appropriates it.

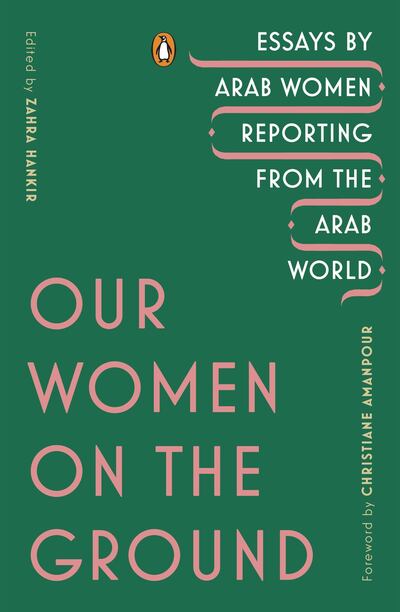

Nonfiction: Our Women on the Ground, ed. Zahra Hankir, translations by Mariam Antar (Penguin Books)

Most of the 19 essays in Our Women on the Ground were written in English, but three moving essays – Words, Not Weapons by Shamael Elnoor, What Normal? by Hwaida Saad and Between the Explosions by Asmaa Al-Ghoul – were originally crafted in Arabic. Each of these essays evokes the difficult choices faced by conflict journalists – for Elnoor in Sudan, Saad, whose work takes him to Syria, and Al-Ghoul in Palestine. The essays are remarkable not only for how they shed light on conflict reporting, but for what they say about the human side of what it means to work as a journalist.