Michael Arad's winning design for the National September 11 Memorial & Museum was controversial. It threw out one of the competition's stipulations: the master plan had called for the voids left by the towers to be overhung by surrounding buildings but Arad chose instead to surround them with an artificial forest. The project's cost threatened to exceed $900 million. There have been disagreements about whether the rank as well as the names of rescue workers who lost their lives should be recorded on the memorial. More recently, an argument flared up over whether the design should include a 17-foot steel cross made from two girders that were found thus arranged in the wreckage. The girders had been embraced as a symbol by Christian groups following the attack, but atheist groups and other denominations were predictably less keen.

The Review: Books

Get the scoop on which of the latest titles are worth making part of your personal collection.

If these points of friction sound fairly mild, imagine how things might have been if a Muslim had somehow won the competition. Imagine if his proposal was found to reference Quranic descriptions of paradise. There would have been quite a fuss, wouldn't there? It would have been like the Ground Zero Mosque thing, only worse, wouldn't it? This is the conclusion a moment's reflection furnishes, and it is corroborated in The Submission, the bustling debut novel by Amy Waldman, a former chief at the New York Times South Asia bureau, now a correspondent for The Atlantic.

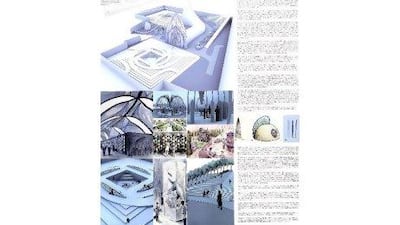

In Waldman's not enormously alternative history of the post-9/11 era, the memorial competition requires submissions to be anonymous. That's how Mo ("as in '-hammad'", quips the blurb) Khan, a Muslimish American with Indian parents, slips through the net. It's 2003. The prize panel comprises society types, establishment artists and one glamorous widow there to represent the wishes of the grieving families, just like on the real competition jury. The widow, Claire Harwell, latches on to Khan's design - a walled garden divided into quarters by canals "shining like crossed swords", with an assortment of real and steel trees filling in the squares. She uses all the moral authority of her bereavement to shame the other jurors into backing her selection. Only when the vote has gone through is Mohammad's identity revealed, to the shock of the panel.

They try to sit on the result, but someone leaks it to the press, and from there an assortment of hypnotic talk-show hosts and bloggers stir up outrage at the possibility that a Muslim might design a monument to the American victims of Islamist terror. These are inexorable forces: one of Waldman's more developed minor characters is a terrier-like journalist who seems to exist solely to dramatise the tabloids' "secular lust" for scandal. Thus the title is revealed as a triple entendre, connoting submission to the machinations of fate along with more obvious plays on Mo's competition entry and the meaning of the word "Islam". Amid a faithful simulation of the city getting hot under the collar about Muslims all over again - scurrilous Post headlines, right-on parties with Rosie O'Donnell and Sean Penn, stern New Yorker editorials that strike Mo "like being called shifty by a roomful of people he had thought were his friends" - the major protagonists spend the rest of the novel agonising over what it is they Really Stand For.

Claire convinces herself early on that her dead husband, a handsomely funded and liberally inclined soul, would have backed Mo to the hilt; she also has the "gilded blankness" of the rest of her life to postpone, which adds a note of arbitrariness to her stand. Paul Rubin, a retired investment banker now chairing the jury, attempts to balance his instinct for political trimming with his respect for process. Towards the other end of the social spectrum, an aimless cut-up named Sean Gallagher mourns the death of his brother and works out his own feelings of inadequacy by stirring up an anti-Islamic rabble.

And then there is Mo Khan himself, less a moderate Muslim than a secular American with a funny name. He drinks, dates women of varied backgrounds and doesn't believe. Nevertheless, as everything touched by Islam is singled out for suspicion in the wake of the attacks, Mo finds himself assuming postures of defiant ambiguity. Paul urges him to withdraw from the competition, which he refuses to do. When his identity leaks, he is besieged with requests that he clarify his intentions for the garden. Was it really designed as an Islamic paradise? Mo won't explain, on the mildly spurious basis that it's racist to ask him. He won the competition, after all. This reticence makes him a blank onto which the public projects its fears. He won't say what he represents, and he won't go away either.

There have been so many duff September 11 novels that it is beginning to seem as though something about the event inherently eludes the grasp of fiction, in the way that sex is sometimes alleged to do. When Don Delillo, John Updike and Jonathan Safran Foer all ended up embarrassing themselves to a greater or lesser degree, there is no shame in falling a little short on one's debut. Moreover, Waldman's angle of approach looks more promising than most. Rather than brooding on the causes of the attacks she focuses on the social processes by which they were interpreted, staking out the querulous, rough-and-ready democracy that novels have made their own since the time of Defoe. One might register doubts about the author's technique: her figurative sense, for instance, tends to be distractingly peculiar. One woman's cheekbones protrude "like tangerines". A little later Claire ponders the likelihood that "shards" of her husband remain embedded at ground zero, raising the more intriguing question of what he was made of in the first place. Yet the overall line of attack seems sound.

The trouble is, it points to a fundamentally satirical mode, but Waldman can't bring herself to skewer her characters. As though it had some charter commitment to political impartiality, The Submission piously pretends that they all have a point to make, a fragment of the larger truth, when on reflection they mainly just seem stupid or venal. It is true that there are comic walk-on parts for the likes of Debbie Dawson, a 50-something Angelina Jolie lookalike who leads a protest group called Save America From Islam. She poses on her website in "a see-through burka with only a bikini beneath" and confidently spouts those ominous Arabic tags so beloved of the reactionary right: taqiya, dhimmi, jihad and the rest. Yet even she is depicted with odd sympathy, granted those quintessential American virtues of showmanship and self-invention, humanised with a trio of playfully uncomprehending teenage daughters. For the focal characters - Sean, for instance - the dilemma of precisely how bigoted to be is treated with real seriousness.

"We will never apologise for not wanting anything Islamic connected to this memorial," he tells a young Muslim woman whose headscarf he previously yanked off at a protest; "It's not personal. It's not prejudice. It's just fact." Waldman makes sure we know what it costs him to draw this line in the sand; indeed, she makes it a moment of perverse heroism, an authentic voice bursting through the gauze of stage-managed reconciliation. One of the competition jurors articulates the novel's centre-ground like so: "[T]wo years on, we still don't know what we're up against. A handful of zealots who got lucky? Or a global conspiracy of a billion or more Muslims who hate the West, even if they live in it?"

There are, of course, sympathetic Muslim characters. We spend a little time with Asma, an illegal Bangladeshi immigrant whose husband died in the World Trade Center. Hers is a simple faith, and she gets a big speech at the town-hall meeting that serves as a final showdown. Mo's thorniness is emphatically chalked up to sexy, Ayn Rand-style ambition and independence of spirit rather than his rather weak Islamic credentials; he and the Muslim campaign group that adopts him as a cause quickly lose patience with one another.

On the strength of her book, there's little reason to think Waldman herself has especially odd views about Muslims. Still, she does seem to have a lot of patience for people who do. Someone like William Gaddis could have taken her premise and turned it into a parade of grotesques and charlatans, which, after all, is what events more or less did. Instead she treats it as a question of individual conscience, and wraps it up in a moment of private reconciliation. That's not a submission so much as a cop-out.

Ed Lake is the former deputy editor of The Review.