Vivid posters fill the ceiling space of an enclosed footbridge leading to a metro station in north-west Hong Kong, transforming it into an unofficial art gallery. The colourful display – printouts of various artists' work – provides members of the public free access to an exhibition of images illustrating the city's protest movement, now into its sixth month, as they make their way to work.

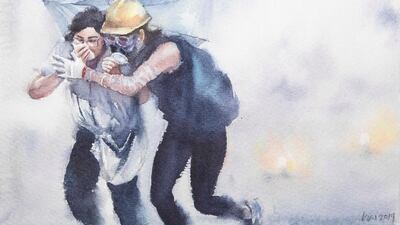

Watercolour pieces by Kin Fung feature prominently. They are blown up across sheets of A4 paper and stuck together as grids across the tiles overhead. A few months ago, this would have been an extraordinary sight, but these spontaneous pop-up spaces have become commonplace throughout the public spaces of the finance centre. As anger and frustration have spilt on to the streets, an explosion of creative energy has thrust art to the surface of a society renowned for its business-driven approach.

Fung, 37, is a hotel interior designer by day, but has become one of the more noted artists of the protest movement by night.

"I began focusing my painting on the movement in the middle of August after being inspired by the demonstrations," Fung tells The National. He started creating watercolours using photographs taken during the protests.

The response to his work has been overwhelming, with one image he posted on Facebook garnering more than 20,000 shares and likes in one day. His work has been plastered all over the city, featured in pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily and exhibited at National Taipei University in Taiwan. He has also had offers from around the globe to buy his work, but, he says it won't be for sale until the collection is complete. He has created about 90 pieces. Fung's effort has not been without criticism. He says he has been accused of romanticising the protests.

"I find the nature of the demonstrations is already romantic because these people are putting their lives on the line to pursue dreams, a better society, a better system. The love, kindness and the bravery are already there and I'm just capturing that feeling; I don't create these images or add new elements to them," he says.

The work has provided Fung with a way to express himself, but he says his intention has also been to offer encouragement to those involved in the protests. “Art provides another platform to reach people – the people who don’t have internet access, those who are sick of hearing about politics, for example.”

Songs and chants have permeated the protests from the start and Do You Hear the People Sing? from Les Miserables – a song about the 1832 Paris Uprising – is among the core theme tunes. The same song has been adopted by students in Iraq protesting the deteriorating economic situation and corruption in their bid to be heard globally.

Carl (name changed on request), a 24-year-old actor who has created a touring musical concert inspired by the movement in Hong Kong, says art is a positive outlet for emotional expression at times like these. "It's very easy to get lost in the emotion that we're engulfed in right now; the hatred, the tears, the anger and the feeling of revenge affecting our lives every day.

“People need a place to share their thoughts and feelings, somewhere to reflect on what we were originally fighting for.”

While protesting, he decided to organise a free performance of the entire Les Miserables soundtrack. "That night, once I was home, I listened to the album and found the message went beyond that one song encouraging people to fight. It's a masterpiece about religion and about humanity, and that's when I came up with this idea of a concert."

Using the instant messaging app Telegram, which protects users' identities, he assembled a team of 20 singers and an orchestra of 12, including a conductor. They are all strangers and from varying backgrounds and age groups. Four weeks later, by Monday, October 28, they were performing for their first audience.

"The fact we didn't know each other was very special," says Carl, who says the performance was different to the 'fine art in theatre' he focused on in his studies. "In those kind of polished concerts, people are buying tickets – they already agree with the message we're conveying. What we're doing for the movement is raw and this in itself is beautifully artistic. This is what is important to me – the meaning of art and what it can achieve.

“I now understand why people cry at their national anthem,” he continues. “That kind of emotion had never existed in my life until now and art is allowing us to communicate that feeling while bringing people together.”

Colourful collages filled with sticky notes have sprung up all over the city, marking out creative community spaces.

People are also becoming involved from afar. For example, a sculptor in Taiwan whose designs have already raised thousands of dollars to help the movement, as well as a dissident cartoonist known by his pseudonym Badiucao, 33, who is originally from mainland China but moved to Australia 10 years ago. The latter says his grandfather was a filmmaker who was persecuted for his art by the Chinese government, an experience that inspired his own work. Badiucao says the current Hong Kong protests really resonate with him and feature heavily in his work as a result.

"Art depicts the human reality – the pain and the sorrow the people suffer," he says. "I see art's function in this protest as [playing] a major role, helping to unite, inspire, comfort and give courage to people, while also countering propaganda." Art is a form of escapism, he says. "Through art we are free to express ourselves." His protest-inspired pieces have even made their way to streets of Melbourne.

Art has long featured in protest movements, particularly street art. Today, Hong Kong is awash with spray-painted slogans scrawled across walls and pavements. Internationally recognised graffiti artist Banksy is another example of how this type of art can make political statements on a global scale. Other examples include the way Chileans in the 1970s protesting against the regime of Augusto Pinochet found ways to create 'untraceable' art.. They used their bodies to depict the torture of citizens, either through public performances or by posting photos of their shows on the streets.

More recently, in Lebanon, one image that gained huge traction was by the Lebanese graphic designer Rami Kanso, who now lives in London. His drawing depicted a woman who kicked a politician's bodyguard in her attempt to defend fellow protesters. In Marie Leduc's book Dissidence: The Rise of Chinese Contemporary Art in the West, the art historian explores how the attribution of rebellion affects the value of art. This could be in terms of using a new concept or material, or by demonstrating disagreement with social or political values.

Leduc focuses on how Chinese artists who have expressed dissent from the government are deemed by the West to be heroes, resulting in their work being held in higher regard. "Every new movement is challenging the previous movements – what art is, what is 'better' – that's what changes over time. It is a group of people – curators, artists, teachers – who step in and say 'this is why it's art', but the art has to have value in the first place." Therefore, major political events act as a catalyst for gaining interest and popularity.

Robert Sinnerbrink, associate professor of philosophy at Macquarie University, in Australia, says contemporary art often "relies on complex ideas, theories, and art-world knowledge that can alienate the public". He believes art produced by dissidents has a greater reach because of the cultural and political background behind the pieces, making it accessible and relatable beyond the world of art.

"Art is a symbol of freedom," Fung says. "People in Hong Kong are using this tool to express their opinions and support others. The nature of art is very powerful and that's why it's become a crucial part of the movement."