Omar Al Hashmi’s gaming room was years in the making.

Perched on the top floor of his three-storey home in Warqa 5 near Dubai Safari Park, it was part of the building plans from the start – a space designed to hold more than 800 video games and more than 50 consoles collected over the past two decades.

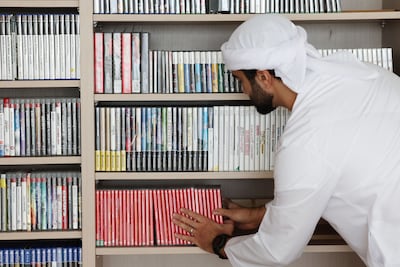

When The National visits, some boxes remain unopened, but there is already more than enough to take in. Floor-to-ceiling shelves in light wood fill one wall, each level packed tight with game cases arranged spine-out.

The bottom row forms a block of blue from hundreds of PlayStation titles. Above are boxes from various generations of Xbox and few bright red Nintendo consoles red indicating collector’s editions.

An adjacent shelf displays a Lego recreation of the original 1983 Nintendo Entertainment System, its miniature screen showing a pixelated Mario mid-jump.

The low wooden console table – still waiting for the television, as Al Hashmi says he is “looking for one with the right specifications” – holds a PlayStation 1, a Sega Genesis and a Dreamcast in open compartments.

Everything is catalogued on an Excel sheet, he says, and he estimates the collection’s value at close to Dh100,000.

“For me, this room is comfort,” Al Hashmi says. “I come here to relax and unwind. I am engineer and have a very stressful job that demands a lot from me mentally, so being in this room and playing helps me forget everything else.

“The funny thing is, because I wanted everything done a certain way, it took a lot of time. I custom-built everything, the shelves, the desk, even the flooring. It was complicated and I had to find very specific people to make what I wanted a reality, but I knew in the end it would be worth it.”

Signs of that personal touch are already visible. Al Hashmi, 31, points over the counter to indicate a hidden tangle of wiring, showing how several consoles are connected so that once the television arrives, he can access them easily.

“I have about fourteen or fifteen machines connected and ready to play immediately,” he says. “I usually keep around fifty or sixty in total. Some are stored elsewhere in the house, but the main ones I play are all here.”

For many Emiratis of his generation, the arrival of consoles in the late 1980s and 1990s marked a significant wave of global pop culture entering local homes. Imported from Japan and the United States, these early machines became fixtures in many childhood homes across the UAE.

“It was like experiencing a whole new world, and for many of us these consoles were given as Eid presents. Many of the consoles I have at home go back to when I was a kid,” he says, running a finger across the old Sega and Nintendo machines. “My mother kept them in storage, and when I rediscovered my passion for gaming, I found them all still there, even the games.”

His first console was the Family Computer or Famicom – the Japanese name for the Nintendo Entertainment System. “I remember my father buying it while we were still living in an apartment. He set it up with the motorbike game Excitebike, which was very popular then. I must have been around five or six years old. That’s my first gaming memory.”

As the only son among sisters, gaming became his form of company. “The consoles became my closest friends. I spent a lot of time with my sisters, but gaming was my space, the place I could just enjoy myself,” he recalls.

The PlayStation One on the lower shelf, released in 1994, holds special meaning. Al Hashmi had to repair it several times over the last five years due to wear and tear. “It’s still with me today because it means a lot,” he says. “Someone got this for me from the United States before it was even released in the UAE. I had just recovered from a childhood surgery, and I remember playing on it and feeling happy again.”

Sometimes Al Hashmi spends weekends not playing at all, just opening old machines, cleaning circuits, tightening screws and testing connections. “I do feel it is an obligation to preserve them, and as silly as it sounds, I grew up with them. There’s an emotional connection there. I want to keep them running and give them the respect they deserve,” he says. “Things will eventually break, but if I can repair something I will, because it is mine and I want to keep it alive.”

These consoles also offer the kind of focused experience that is hard to find in the era of online gaming. In an old console, he notes, there are no messages, updates or notifications. It is just the game itself.

“In the digital world you stream things, but I prefer taking a disc or cartridge, plugging it in, and starting without connecting to the internet or accepting any terms and conditions,” he says. “Having the disc in front of me and putting it into the console feels different. It is a small action, but that extra focus and patience when playing the game changes the experience completely.”

For Al Hashmi, collecting has never been about money or display. It is about holding on to memory in a way that cannot be uploaded or archived online. Each cartridge and console marks a chapter of his life – a childhood holiday, a hospital stay, a first salary of a new job spent. “Everything here reminds me of something,” he says. “Every piece has a story. You can take pictures and post them online, but they do not carry the same feeling. When you touch the real thing, it brings it all back.”

It is a principle he is applying to the progress of the gaming room. “When I first moved in, it was completely empty. I took my time with the design. I wanted it perfect, exactly how I imagined,” he says.

“Maybe one day my kids will play these the way I did. To me, that is the real future of the collection.”