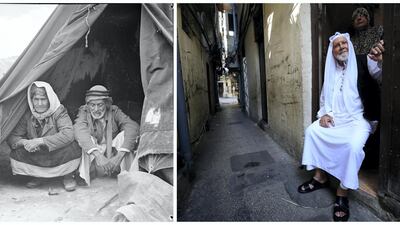

George Salameh's family has lived in the Palestinian city of Bethlehem for 70 years.

Still, he prefers his family be called "Al Yafawi", meaning "of Jaffa", an ode to the Mediterranean coastal town his family left in 1948 and still considers home.

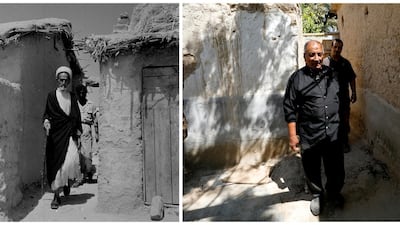

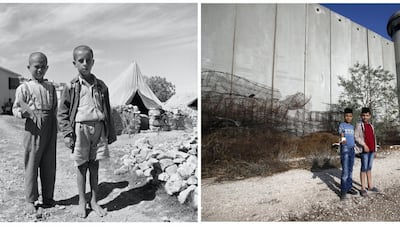

Mr Salameh, like many Palestinians whose families were made refugees following the mid-20th century war that surrounded Israel's creation, views his presence in the Israeli-occupied West Bank city as temporary.

Other Palestinian refugees are scattered from the Gaza Strip to Lebanon, Jordan and Syria. Many still hold iron keys that belong to homes they fled or were forced to flee amid what Palestinians call the "Nakba", or catastrophe, in 1948.

Mr Salameh, 59, now runs a falafel, ful and hummus restaurant, just off Bethlehem's Manger Square. The motto "since 1948" is emblazoned on the restaurant's menus and its waiters' shirt sleeves.

He says his membership card from UNRWA – the UN's agency for Palestinian refugees – guarantees his right under international law to return to his family's home in Jaffa, which now sits in central Israel, some 78 km away.

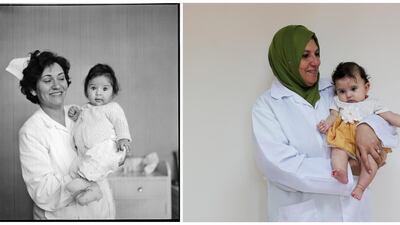

The UN General Assembly voted on Friday to renew UNRWA's mandate to provide education, health and relief services to more than 5 million Palestinian refugees across the region.

UNRWA argues its services are needed "in absence of a solution to the Palestine refugee problem".

But Israel refuses the right of return Mr Salameh and other refugees claim, fearing the country would lose its Jewish majority.

Mr Salameh admits his hopes for going back remain dim.

"We don't believe there will be a right of return. It's like an anaesthetic, it takes the pain away, but it is not a cure," he said.

In the Gaza Strip, Zakeya Moussa says her family once owned 16 acres of land just north of the coastal enclave's fortified border with Israel.

Ms Moussa, 63, has spent her entire life living in Palestinian refugee camps in the Strip, which Israel has kept under blockade since 2007 citing security concerns from its Islamist rulers Hamas.

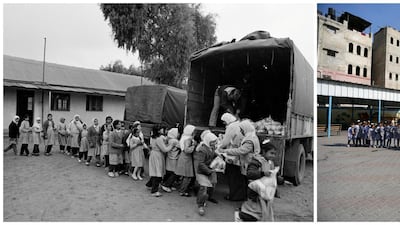

Near Ms Moussa's home in Gaza's Beach refugee camp on the shores of the Mediterranean, Palestinians were unloading sacks of flour they receive from UNRWA, which provides aid to over half of the enclave's 2 million residents.

"UNRWA gives us flour, plant oil, beans and milk, we get treated for free, we get medication... We are nothing without UNRWA," Ms Moussa said.

She says her family's land had a house surrounded by tracts of fruit and vegetable fields, all now north of the Strip's Erez border crossing with Israel.

Under different circumstances, it would be just a short walk away, she said.

"If I started walking now, I would be there in the afternoon."