BEN GUERDANE, TUNISIA // Khared Zawi is finishing his restaurant lunch and watching television, transfixed as the newsreader's voice reports atrocious violence in Syria over amateur video of explosions and corpses.

"It's not acceptable," says the young Tunisian from behind his wispy beard. "No human on this planet will accept it, and no Arab."

In crushing a nationwide uprising, Bashar Al Assad has insulted Islam by destroying mosques while followers of the Syrian president's Alawite branch of Shia Islam have killed Sunni Muslims, Khared says. "I'm supporting the guys fighting Bashar."

During the 16 months in which peaceful pro-democracy protests became a bloody and increasingly sectarian conflict between government forces and rebels, Syria has become a focal point of outrage across the Arab world, and a trickle of young men embracing militant Sunni Islam have gone to fight there.

As many as 12 of them may be from this dusty Tunisian border town. Their families woke up one day to find a son or brother mysteriously vanished. Some of the missing loved ones disclosed their destination with a single telephone call to say they were in Turkey and heading for Syria. In at least one case, a terse phone call from a stranger said the young man was dead.

The nature of their activities was never explicitly revealed, but some of them appear on a list given by Syria to the United Nations of 26 men held by the regime as "foreign fighters", of whom 19 were Tunisians.

"On February 28, he was here," said Ali Dhifellah of his son, Mohammed, "and then he called on March 1 and said he was in Turkey." The young man, the sixth of his eight sons, told his father he planned to volunteer in refugee camps in Syria or Turkey.

Mr Dhifellah is sitting with his wife in a shabby communal room on the outskirts of this hardscrabble town about 30 kilometres from Libya, where many make a living from smuggling. The couple are exhausted with grief.

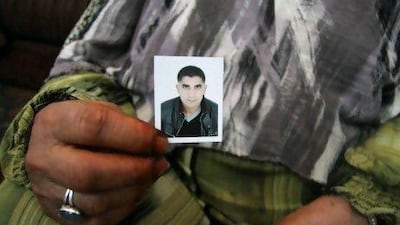

Flicking through pictures of his son on his mobile phone, Mr Dhifellah says Mohammed was the most religious of their children, that he prayed a lot and that he had worked with refugees during last year's conflict in Libya, but that his disappearance had come as a shock.

"He could never do this on his own, there are some people behind him. Who they are, I don't know." Other families tell stories that also seem to point to an organised flow of fighters to Syria, with groups of young men vanishing in small groups at the end of February this year.

Mabrouk Hillal's brother, Walid, 21, said he was going to the Tunisian capital for special training in his hobby, kung fu. "He disappeared on February 24," Mabrouk says. Walid was not heard from again until the family received a telephone call on April 24, telling them in two gruff words that he had become a martyr.

His mother and most of his brothers insist that, without proof, they could not say for sure where Walid was.

But one brother, Fethi, wearing the beard and clothing adopted by fervent Muslims here, said that "naturally" his brother died fighting in Syria. "It's a good thing, it's a duty," he said. "I would like to do it, but I couldn't. He was braver than I am."

The Syrian government has long blamed the violence on foreign fighters and extremists, but the arrival of fighters such as the boys of Ben Guerdane is a relatively recent phenomenon, according to Aaron Zelin, an expert in jihadi movements at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

"The collective evidence suggests that between 700 and 1,400 foreign fighters have entered or attempted to enter the country this year alone," Mr Zelin has reported. Senior imams within Al Qaeda have called for followers to travel to Syria to fight, he wrote.

Jihad is not a new phenomenon in Tunisia, as residents of Ben Guerdane point out. "The infrastructure for jihad was already there," said Alwi Farrah, a hotel owner who estimated that dozens of people from the town had travelled to Iraq to fight during the height of the war there.

Documents found in the border town of Sinjar in Iraq, studied by the US military, suggest that a substantial proportion of foreign fighters who sought to fight or conduct suicide bombings with Iraq's offshoot of Al Qaeda were from Tunisia.

A growing Salafist movement may also be creating an atmosphere conducive to militant feeling in Tunisia now.

Since the fall of the autocratic former leader Zine El Abidine Ben Ali last year, tight curbs on religion have been lifted and prominent religious leaders, including one known as Abu Ayyadh Al Tunisi, have called for the liberation of Syria in speeches, while stopping short of calling openly for fighters to travel there.

In Ben Guerdane, there has been a marked rise in the number of people who outwardly display the clothes, beards or full-face veils adopted by Salafists. For a local barber, Abdulwahhab Kheireddin, it has been bad for business.

"Before the revolution, everyone used to shave their beard on a daily basis, otherwise he would be investigated," he said. Now, men who used to be regular customers he often sees with long beards.

For Mr Kheireddin, as for most other people in the town, appearance is a matter of personal choice, but he is critical of the young men who headed for Syria. "Why are they going there? To fight Arabs and Muslims?"

Even the head of an evangelical Islamist group in the town did not endorse jihad in Syria. Hamza Al Jery spent four years in prison under Ben Ali for distributing religious material smuggled in from Libya, and now hosts lectures and runs a Saudi-funded religious library in a small centre.

He said Tunisia was going through an Islamic renaissance and, in an age when people had access to inflammatory religious material on the internet, "the young excited people are outnumbering the sheikhs, making it difficult to control them".

Although people are free to choose to fight in Syria, he said: "I don't think they will bring anything new.

"They are being used as political cards by the Syrian regime. Those guys are reinforcing the argument of the Syrian regime."